Introduction

Growing up in a middle-class family with five siblings, my formative years were shaped by the love and care of my elders, instilling in me a sense of confidence and freedom. Among them, my father emerged as the most influential figure, guiding me with his hard work and selfless values. As I reflect on my educational journey and professional life, I realize how my father’s schooling continues to resonate, impacting my academic pursuits and shaping me into an educator who seeks to inspire and transform the lives of others.

The Enduring Legacy of My Father: Inspiring Values in My Academic Journey

Growing up in a modest family in the Baitadi district, my father’s determination, love for education, and selflessness left an indelible impact on my values, beliefs, and personal growth.

Despite their humble circumstances, my father’s family recognized the transformative power of education, impressing upon him the importance of prioritizing learning for a brighter future. Embracing this wisdom, he excelled academically and obtained top honours in the Kanchanpur district, the western part of Nepal. Working part-time to support his further studies, he completed B.Ed. in mathematics from Tribhuvan University, Nepal, and devoted over 36 years to teaching secondary-level mathematics in rural areas.

My father’s life experiences taught me the value of hard work, honesty, and unwavering determination to achieve my goals. His struggles also instilled in me a sense of gratitude for the opportunities I have today. His most profound lesson, however, was selflessness, his unwavering dedication to his family and society left an indelible impression on my character. As I pursued my academic journey, my father’s influence continued to guide me. Although my circumstances were more privileged, his lessons taught me that diligence and integrity make success possible.

His teachings not only shaped me as a good person but also as an authentic individual. I am determined to pass these invaluable lessons to my future family and students. With his enduring legacy as my compass, I seek to inspire and transform lives, just as my father has done throughout his remarkable journey.

Empowerment Through Education: A Personal Academic Journey

My academic journey commenced at home, where my family played the role of my first teachers, introducing me to alphabet belts and basic numbers. Though I began my formal education in a government school like my siblings, I had the privilege of studying in private (boarding) school (first in my family). This choice garnered public attention and prestige in our village, underscoring the value of education.

During my primary education, I excelled in memorization-based learning, securing top positions in my class. However, the system of rote learning limited my true understanding of the subjects. Shifting to government education posed initial challenges due to larger and more diverse classes, but I adapted over time, benefiting from a more flexible learning environment, albeit lacking student-centred approaches.

Upon completing my SLC, I went to Nainital India for my I.Sc., however I realized that my I.Sc. didn’t align with my interests, and faced language difficulties and homesickness. My family, understanding my predicament gave me the freedom to decide my academic path, leading me back to Mahendranagar, my hometown.

Embracing my interest in English, I pursued I.A. with English as my major subject. My academic journey continued rapidly, culminating in a B.A. with a major in English from Mahendranagar. My pursuit of higher education led me to Kathmandu, where I completed my M.A. in English literature from the central department of English in Kirtipur, achieving a first division. During my master’s studies, I harboured aspirations of becoming a police officer, inspired by the bold heroes of Hindi movies. However, my passion for teaching gradually surfaced, steering me away from the police force.

In this journey, education has played a pivotal role in empowering me intellectually. It provided me with knowledge, skills, and critical thinking abilities, enabling me to navigate various academic pursuits successfully. Furthermore, education has empowered me economically by opening doors to career opportunities and professional growth, allowing me to contribute meaningfully to society.

Education also fosters social empowerment, equipping me with the ability to share knowledge, mentor others, and contribute to the transformation of education in Nepal. Through my role as an educator, I have had the privilege of training teacher educators, presenting research papers at national and international conferences, and integrating innovative teaching strategies with ICT in language classrooms.

As I reflect on my academic journey, I recognize that education has been the key to my empowerment in multiple dimensions. Not only has it enriched my personal and professional life, but it has also instilled a deep sense of responsibility to empower others through the dissemination of knowledge and a commitment to transformative education.

Empowering Teaching Through Innovative Integration of ICT

As I embarked on my teaching journey at Darchula Multiple Campus, Khalanga, Darchula, Nepal in 2009 after completing my M.A. in English Literature from Tribhuvan University, I initially questioned whether teaching would become my true passion and profession. Not having an ELT background, my first experiences in university-level ELT classes left me feeling somewhat apprehensive. However, the positive responses and appreciation from both students and colleagues ignited a newfound enjoyment in teaching, leading me to realize that teaching was indeed my passion.

To improve my teaching skills and enhance my expertise in English Language Education further, I pursued a one-year B.Ed. and M.Ed. from Tribhuvan University. Determined to stay up to date with the latest pedagogy and educational technologies, I delved into integrating ICT into my ELT classrooms. The availability of ICT infrastructure, including computer labs, laptops, projectors, multimedia smart boards, and internet facilities, provided valuable tools to enrich the teaching and learning process.

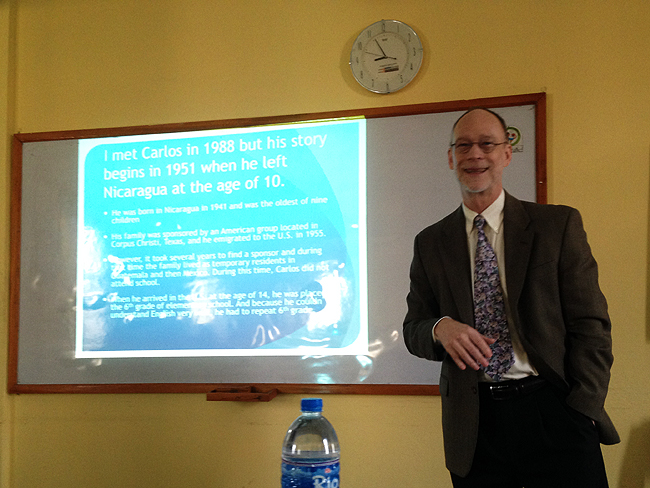

The integration of ICT, though initially challenging, proved to be a motivating force in my teaching practices. Participating in various training sessions, workshops, webinars, and conferences, and learning from online resources like YouTube videos, I gradually adapted to using ICT more effectively in language classrooms. My colleagues often sought technical support from me when incorporating educational software such as MS Teams and Zoom during the transition to online classes amidst the pandemic.

Witnessing my students’ satisfaction and a keen interest in my classes further fueled my motivation to innovate in teaching by strategically incorporating ICT. A significant incident that highlights this impact occurred on 5th July 2021 when I was allowed to conduct ICT training for my colleagues at Far Western University Darchula Multiple Campus Khalanga Darchula. The training focused on using MS Team for upcoming online classes, and it became evident that many faculty members lacked familiarity with ICT in education. Their enthusiasm to learn and improve their ICT practices was inspiring. Guiding them through the basic functionalities of MS Team, such as creating class schedules, adding students as members, conducting quizzes, and facilitating group discussions, the session proved to be both engaging and fruitful, garnering appreciative comments from the participants and the dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Despite facing challenges within the academic environment and culture, where well-performing teachers are sometimes undervalued or discriminated against based on political affiliations, I have remained steadfast in fulfilling my professional duties honestly and responsibly. The support and belief from my family, friends, and students have been instrumental in sustaining my resilience.

Through the transformative power of education and the innovative integration of ICT, my passion for teaching has flourished, empowering me intellectually and professionally. Beyond my personal growth, I aspire to be an agent of change, promoting the meaningful use of ICT in education and contributing to the advancement of the educational landscape in Nepal.

M.Phil. at Kathmandu University as a Gateway for Transformation

I decided to pursue an MPhil in English language education from Kathmandu University with the unwavering support and encouragement from my family, friends, and students. Their belief in my abilities and the significance of advancing my academic journey propelled me to seek an institution that would catalyze personal growth and transformation. In this esteemed institution, I got amazing mentors, whose mentorship equipped me with both theoretical knowledge and practical competencies, instilling in me the confidence to implement cutting-edge teaching strategies and adapt to the ever-evolving needs of my future students. Through their guidance, I deepened my understanding of English language education and acquired the necessary skills to become a proficient teacher for 21st-century learners. Engaging in teacher professional development activities, I was exposed to innovative teaching methods, educational technologies, and effective pedagogical approaches that are most relevant in today’s dynamic classroom environments.

Furthermore, the vibrant academic environment at Kathmandu University fostered a strong sense of community among fellow students. Collaborative projects, discussions, and academic events enriched my learning experience and provided me with diverse perspectives on educational practices. This supportive network of peers and colleagues further contributed to my personal and professional growth, creating a nurturing environment for exploration and intellectual development.

During my M.Phil. journey at Kathmandu University, I experienced a profound personal transformation and achieved notable professional growth. Embracing innovative teaching strategies, I contributed to the academic field through publications and disseminated knowledge to a broader audience. Additionally, my academic journey extended into teacher education and research, as I provided training and presented research papers at national and international conferences, contributing to the advancement of Nepal’s education system. This transformation has empowered me with the confidence to foster positive change and cultivate a passion for learning among future generations.

Summing up

My academic journey has been a transformative experience, catalyzed by the influence of my father’s dedication to education and selflessness. From the early years of learning at home to my pursuit of higher education at Kathmandu University, I have been intellectually and professionally empowered. By integrating innovative teaching methods and ICT in the language classroom, I have witnessed heightened student engagement and satisfaction. This journey has also enabled me to contribute actively to the field through my publications and knowledge-sharing endeavours with fellow educators. Supported by the unwavering belief of my family, friends, and students, I am determined to leverage the transformative power of education, creating a positive impact on the lives of students, and fostering progress within Nepal’s education landscape as I continue to evolve as an educator and researcher.

About the Author: Dammar Singh Saud is an assistant professor at Far Western University, Nepal. He holds an M.A. in English Literature and an M.Ed. in English Language Education. Currently pursuing an MPhil in English Language Education at Kathmandu University, his research interests include ELT Pedagogy, ICT in ELT, Teacher Professional Development, and Translanguaging.