Bal Ram Adhikari

Mahendra Ratna Campus, Tahachal

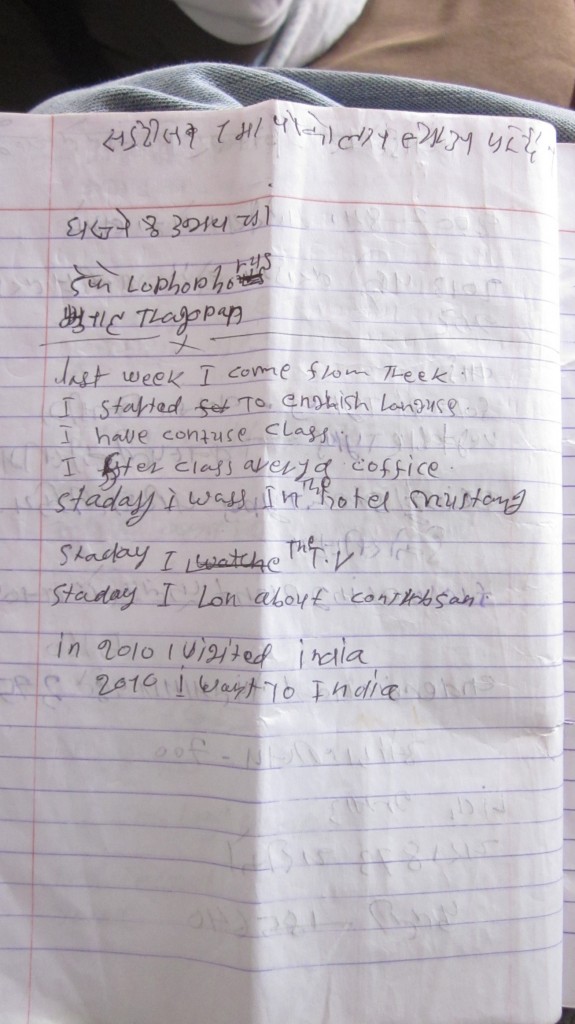

The contribution of reading to the development of overall language proficiency cannot be overrated, especially in the EFL contexts like ours where students’ contact with English is almost what they read in and outside the classroom. Our students often end up with reading, and with some vocabulary and grammar practice activities that follow. Sometimes, the position the reading skill has enjoyed in the course, classroom practice and examination is at the expense of other vital skills of English, namely listening and speaking. Despite this, written texts are the most accessible, reliable and structured source of English input for the majority of our students, who, in their attempt to appropriate the foreign tongue, are struggling in the under-resourced academic environment. The challenge that looms large in front of university teachers teaching the reading courses is how to assist their students in exploiting the reading materials at the fullest for multiple purposes. The purposes range from reading for gist, specific information, and language awareness to extensive reading for one’ pleasure as well as professional development.

Having students read a variety of texts in the classroom and encouraging them to do the same outside are motivated by the twin-goals of knowledge acquisition and language acquisition. That is, the ideal combination of knowledge component and language component leads to the organic development of language in students. It is possible when the latter is subservient to the former. The focus on the knowledge component engages students in the comprehension, analysis, synthesis, application, evaluation and most importantly creation of knowledge by employing the linguistic and non-linguistic resources at their disposal. The courses Reading Writing and Critical Thinking, Expanding Horizons in English, Readings in English, prescribed by Tribhuvan University for its B Ed and M Ed English students reflect the emphasis on the combination of knowledge and language components, and the integration of language skills backed up by the critical thinking component. For this, the reading textbooks under these courses consist of authentic texts from the diverse fields of knowledge such as humanities, pure and medical sciences, social sciences, environment science, psychology, religion and mythology, spiritualism, language and society, gender studies, cultural studies, mass communication and technology, to name but a few. Obviously, it is our first experience of being exposed to such a vast array of authentic texts from different fields. As a result, the teachers and students both are overwhelmed by the demand made by the courses. The challenges they have been facing since the implementation of the courses in 2010 are many. The teachers express mixed feelings about the nature of the courses and possibility of their effective implementation.

Against this backdrop, I’d like to shed light on some of the challenges that teachers and students of these courses are facing. Also, I’d like to make some workable suggestions to overcome them. To serve this purpose, I have drawn on my own experience of working in these course books as a contributor and trainer. Some of the insights into the challenges faced by the teachers and students are also based on my personal communication with the teachers during the different training programs. I begin with the common aspirations expressed in these reading materials, then move to underlying theoretical assumptions before I discuss the common challenges and ways of overcoming them.

Common aspirations expressed in the course books

The prescribed books, namely, New Directions: Reading, Writing and Critical Thinking (ed. Gardner, 2005), Expanding Horizons (eds. Awasthi, Bhattarai and Khaniya, 2010) are prescribed for Bachelor’s first and second year students majoring in English education, and Reading Beyond Borders (eds. Awasthi, Bhattarai and Khaniya, 2011) is for Master’s second year students. These books contain the authentic reading materials from the diverse fields of study. The aspirations expressed by the editors of can be summarized in the following points:

- Enriching students’ vocabulary through implicit and explicit exposure to authentic written texts.

- Fostering critical thinking in the reading and writing process.

- Emphasizing the role of the critical thinking component in the English for Academic Purpose

- Training students in reading and writing strategies through intensive reading activities in the classroom so that they can transfer such strategies to out-of-classroom reading and writing.

- Fostering simultaneous development of English language acquisition and subject matter acquisition.

- Encouraging students to use English as a means of accessing content information on the diverse fields of contemporary world.

- Integration of all language skills and language aspects.

The editors are also aware of the fact that academic or advanced reading is incomplete without academic writing. That is, the tasks for students are developed in such a way that reading and writing feed off each other and the critical thinking component backs up these two processes.

Theoretical assumptions of the courses

The following theoretical assumptions seem to underpin the reading courses:

- Reading is an interactive process.

- Reading is a purposive process.

- Reading is a critical process.

- Reading proficiency calls for extensive reading habit.

Of them reading as interactive and critical processes deserve a special mention, for they challenge the traditional notion of reading as a passive skill and the reader as the mere recipient of information. Contrary to the passivity of the reader and mere receptivity of information, these two assumptions redefine reading as a highly productive, interactive and dynamic process. To be more specific, reading as a critical process has been the prime focus of the courses, at least in theory.

Reading as a critical process

Any reading which is critical is also purposive and interactive. Reading as a critical process can be interpreted from the two dominant perspectives. The first perspective deals with the cognitive aspect of reading that requires readers to engage in the higher order thinking as postulated in the Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom 1956, and Grondlund, 1970, as cited in Law and Gautam, 2012, p. III). The second perspective takes reading as “a social process” (Kress, 1985, as cited in Hedge, 2000, p.197). According to Hedge “from this perspective, texts are constructed in certain ways by writers in order to shape the perceptions of readers towards acceptance of the underlying ideology of the text” (ibid.). A text is a dynamic space where the ideology (i.e. socio-cultural, political and professional beliefs and values) of the reader comes in direct contact with that of the writer often in the form of either resistance or submission. Critical reading in both cases calls for the active interaction between conscious readers and the writer. Such interaction can take place in two different but interrelated modes.

a) Interaction with the text

In this mode of interaction, the reader interacts directly with the text. It can also be termed as the outer-projected interaction in which the reader interacts with the textual features: its theme, characters, linguistic features, cultural elements and writer’s style. This mode of interaction is active mainly, but not necessarily exclusive to, the while reading phase, which focuses on the extraction of the required information and comprehension of the gist. The strategies employed by the reader can be receptive reading, skimming, scanning and intensive reading.

b) Interaction with the Self

Comprehension is necessary but not sufficient. Readers have to transcend the mere extraction and comprehension of information. They should relate what they have comprehended from the text to their experiential world, reflecting on what they have learned, what it means to them, and pondering how they can use it. This mode of interaction can also be termed as the inner-projected interaction. Readers who do not relate textual information to their purpose, experiential zone and existing knowledge fail to move upward in the higher order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, evaluation and creation. It is also difficult for them to challenge the writers’ viewpoints and maintain critical distance from them. This mode of interaction is active mainly, but not necessarily exclusive to, pre-reading and post-reading phases. The reading strategies employed can be reflective and refractive.

Organization of the textbooks

The texts from different sources are structured under different thematic headings. The overall organizations of the materials can be divided into macro- and micro-levels. At macro-level, each book is thematically organized under different headings such as Intercultural Communication, Education, Mass Media and Technology, Gender Roles and Work (New Directions, 2005), Humanities, Social Sciences, Human Rights and Freedom, Education and Language Teaching, Globalization and Postmodernism, East and West, Masterpieces, War and Piece, Travel and Adventure, Health and Medical Science, Sports and Entertainments, Science and Technology, Nature, Ecology and Environment ( Expanding Horizons in English, 2010), and Literature and Art, Democracy and Freedom, Multiculturalism, Globalization and Postmodernism, Philosophy and Ideology, Memoire and Revelation, Science and Technology, Sports and Entertainments, and so on (Reading Beyond Borders, 2011). Each thematic heading is fleshed out with different relevant texts. The variation in the macro-level organization seems to be the matter of choice, interest, and focus of the editors. At micro-level, each chapter is structured under the different headings such as Unit Opener, Core Readings, Making Connections, Additional Readings, and Easy Topics (New Directions); Before You Read, Vocabulary, Dealing with the Text, and Beyond the Text (Expanding Horizons in English); Dealing with the Text, and Beyond the Text (Readings Beyond the Borders).

Classroom pedagogy

The classroom pedagogy suggested in all these course books is an integrated approach. The teachers are supposed to interpret the term integration from two perspectives: integration of content areas with the English language, and integration of major language skills and language aspects. The first implies that learning English with relevant content areas leads to deeper processing and hence ensures better output. The second implies that integration of two or more language skills is a natural phenomenon in real life language use, and vocabulary and grammar are integral components of language skills. Hence, “students might read and take notes, listen and write a summary, or respond orally to things they have read or written (Richards and Rodgers, 2001, p. 208).

Major challenges

The type and the magnitude of challenges faced by teachers and students vary depending on the nature of texts and the amount of schematic knowledge the readers bring in, and resources available to approach these texts. The common challenges can be discussed under the following headings:

1) Nature of the texts

The text is what students interact with for the enrichment of language and subject matter knowledge. The output from this interaction cannot be high if the the text itself poses a problem for students. The interaction between students and texts can be negatively affected if the text has its origin in the culture almost unknown to the students and if its language and subject matter are too taxing for them to process. Povey (1979, as cited in Celce-Murcia and Hilles, 1988, p.123) has used the terms cultural, linguistic and intellectual humps or barriers for these constraints imposed by the reading text itself.

a) Cultural barriers: Cultural barriers include imagery, tone and allusion (Celce-Murcia and Hilles, 1988, p. 123), along with myths, folk tradition, religion, national history and a way of life embedded in the text. The reading materials which belong to foreign cultures are more difficult to interpret than those belonging to readers’ national or regional cultures. Because of the cultural elements embedded in them, the chapters such as Paradise Lost, Contemporary Writing in Arab Countries, Death Valley, and Iliad from Expanding Horizons are obviously more challenging for our students than OM, The Bhagvat Gita and The Necessity of Religion. The texts with foreign cultural elements require sufficient contextualization before students deal with them.

b) Linguistic barriers: Linguistic barriers include complexity of syntax, lexicon and style of the text. Language used in the text can be seen as one of the major barriers to the effective interaction between text and students. This barrier seems formidable, especially for those (both students and teachers) who lack extensive reading in English. The chapters such as The New Age of Connectivity, What is a Novel? , Contemporary Writing in Arab Countries, The Birth of Sex Hormones, etc. from Expanding Horizons do not lend themselves to easy interpretation because of their jargon, complex sentences and formal style. Similar is the case with the chapters like Post-structuralism, Asymmetries of Commerce and Culture, Religious Tolerance- Peacemaker for Cultural Rights, and Japan included in Reading Beyond Borders. Because of area-specific words, lengthy and complex sentence structures, and highly formal style, many texts in the course books are linguistically too challenging for the readers to process the content. These texts call for a lot of language preparation work before making entry into them.

c) Intellectual barriers: Intellectual barriers occur when the reader lacks “intellectual maturity and sophistication necessary to appreciate, relate to, and comprehend the subject matter” (Celce-Murcia and Hilles, 1988, p. 123). The texts such as The Birth of Sex Hormones, The Science of Heredity, The Promise of Global Institutions, The Age of Connectivity and Cubism are not intended for general readers. These texts represent the recent findings in their respective fields. The editors seem to presuppose that students have sufficient knowledge in the fields like genetics and anthropology, Information Technology, and painting and sculpture. The teachers during the training often complained that the issues discussed in these texts are too difficult for them to understand, let alone their students.

2) Attitudes to reading skill

The prevailing attitude towards reading as a receptive skill has also remained as one of the major barriers to the successful implementation of the courses. As discussed above, the courses embrace the recent trends in teaching reading as an interactive and critical process while the prevailing classroom practice shows that all that a good reader needs is the ability to answer the comprehension questions given in the course book. Similarly, there seems to be a gap between what the teachers and students expect from each other. The teachers expect their students to read the text and answer the questions that follow. Students, on the other hand, expect their teachers to read the text for them and supply summary and answers. This classroom practice fails to see the value of pre-reading and post-reading activities and is almost confined to the comprehension phase of reading. As a result, the integration of other language skills with reading is missing. For such teachers and students the reading activity begins from and ends with the given text itself, i.e. for them the text is the end not the means.

3) Text as an end: Those we consider reading as a mere receptive process tend to take the text as an end to itself. Such a view undervalues the multiple purposes that the prescribed reading materials can serve. A text should be taken as a means to access information and language resources. In other words, a text is a means to activate the reader’s schematic and language knowledge, to play with various writing styles and strategies, and to create another text that either conforms to or resist the writer’s stance. Its classroom implication is that readers should begin from and end with the non-textual world vial the textual one.

4) Institutional constrains

Lack of adequately trained teachers, sufficient orientation to them, sufficient preparation time available for them, and the large class size have remained other challenges to the teachers and students.

Insights into the nature of the courses, organization of the reading materials, the suggested classroom pedagogy, and challenges faced by the students and teachers in the actual classroom can help us to think of the areas to be addressed and design effective classroom procedures.

Some basic questions to be addressed

It is important that the teachers address the following issues before engaging students in the actual act of classroom reading:

- What to do before, during and after students read the text.

- How to guide students through the text to read meaningfully, purposively and critically.

- How to have students read/learn cooperatively in pairs and groups.

- How to assist students in connecting what they already know to the text and what they have learned from the text to the real world.

- How to integrate the reading skill with other skills.

Classroom procedures

The prescribed course books Expanding Horizons in English and New Directions have followed the established practice of the three-phase procedure: Pre-, While-, and Post-reading. These phases can also be termed as anticipation phase, building knowledge phase and consolidation phase respectively (Crawford et al., 2005). Crawford et al. have used the organic metaphors to highlight the value of these phases of critical thinking and productive learning. In the anticipation phase a wheat seed is planted in rich soil, the seed sprouts and a plant grows in the building knowledge phase, and finally in the consolidation phase the head of wheat is mature, and contains seeds of many other plants (2005, p. 4-5.)

New Directions and Expanding Horizons both are rich in the variety of reading tasks under each phase. However, Reading Beyond the Borders has skipped the Pre-reading phase, leading the students to an abrupt confrontation with the text. If not handled by an experienced and trained teacher, the students are likely to experience a sense of bewilderment for want of background information required to enter the text.

a) Pre-reading phase

This is the preparation or schemata activation phase. While engaging students in the pre-reading or anticipation tasks given in the books and teacher’s manuals or designed by the teacher himself, the he should

- respect and capitalize on the student’s experiences, knowledge and language resources.

- assess informally what they already know, including misconceptions (Crawford et al, 2005, p. 2).

- provide a context for understanding new ideas.

- ask them to write down what they Know about the topic and what they Want to learn or expect from it.

b) While Reading Phase

The students in this phase deal with the text. The teacher should set tasks that require them to inquire, find out and make sense of the reading materials. The while reading tasks should encourage students

- to indentify the main points and their supporting details.

- to find new pieces of information from the text.

- to compare their expectations with what is being learned, and to revise them or raise new ones (Crawford, et al. 2005, p.3).

- to react to the opinions expressed, ask themselves questions, and to predict the next part of the text from various clues (Hedge, 2000, p.210).

c) Post-reading Phase

This phase takes the students beyond the text. However, the tasks in this phase should be tied up with pre-, and while-reading phases, and should lead to writing and speaking tasks. That is, this phase has both backward-looking and forward-looking purposes. The instructor in this phase should set the tasks that require the students:

- to reflect on what they have learned by summarizing the main ideas in their own words.

- to interpret the main ideas.

- to share opinions in groups

- to agree or disagree with the writer’s stance.

- to role-play major situations or characters given in the text.

- to create a parallel text.

Although the classroom reading procedures are divided into the three different phases for the theoretical convenience, these phases and activities under them lie in the continuum. In the actual classroom practice, it is almost impossible to say when one ends and another begins. Such compartmentalization is not desirable either.

Conclusion

Compared with the previous ones, the courses Reading, Writing and Critical Thinking, Expanding Horizons, and Readings in English prescribed by Tibhuvan University for its Bachelor’ and Master’s programs mark a paradigm shift in English Education . The reading texts under these courses have embraced current trends in ELT that gives priority in flooding ESL/EFL learners with relevant, contextualized and authentic texts. However, it goes without saying that the effectiveness of these courses depends on how the course books are exploited in line with the aspirations expressed in them. Both teachers and students should bear in mind that there is no easy and direct route to journey into the textual world. Much depends on how clear we are about our destination, how well prepared we are for it and how skilled and experienced we guides are.

Awasthi, Bhattarai and Khaniya (Eds.) (2010). Expanding horizons in English. Kathmandu: Vdhyarthi Prakashan.

Awasthi, Bhattarai and Khaniya (Eds.) (2011). Reading beyond borders. Kathmandu: Vdhyarthi Prakashan.

Celce-Murcia, M. and Hilles, S. (1988). Techniques and resources in teaching grammar. Oxford: OUP.

Crawford, A., Saul, E.W., Mathews, S. and Mkinster, J. (2005). Teaching and learning strategies for thinking classroom. Nepal: Alliance for Social Dialogue

Gardner, P.S. (Ed.) (2005). New directions: Reading writing and critical thinking. Cambridge: CUP.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and learning in the language classroom. Oxford: OUP.

Law, Barbara, and Gautam, G. R (2012). Teachers’ manual: Expanding Horizons. Kathmandu: NELTA.

[1] I am grateful to Dr. Barbara Law and Ganga Ram Gautam with whom I had an opportunity to work as a contributor to the teachers’ manual for Expanding Horizons. The basic outline of this article was developed during the training we (Barbara and I) conducted together in Gulmi.

Like this:

Like Loading...

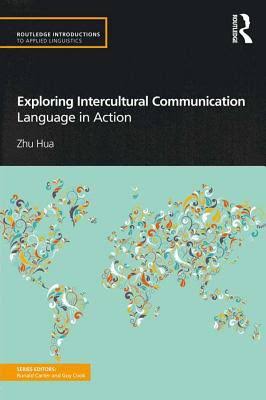

Bal Krishna Sharma, PhD is an Assistant Professor of TESOL in the Department of English at the University of Idaho, United States of America. He teaches courses on applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, intercultural communication and second language acquisition. He is one of the founding members of ELT Choutari, and a co-editor of the Journal of NELTA from 2009 to 2012. Dr Sharma has a good exposure of national and international conferences. In this connection, our Choutari editor Jeevan Karki has spoken to him to explore the conferences then and now, roles of conferences in the professional development of the ELT practitioners and other forms of continuous professional development.

Bal Krishna Sharma, PhD is an Assistant Professor of TESOL in the Department of English at the University of Idaho, United States of America. He teaches courses on applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, intercultural communication and second language acquisition. He is one of the founding members of ELT Choutari, and a co-editor of the Journal of NELTA from 2009 to 2012. Dr Sharma has a good exposure of national and international conferences. In this connection, our Choutari editor Jeevan Karki has spoken to him to explore the conferences then and now, roles of conferences in the professional development of the ELT practitioners and other forms of continuous professional development.

This book addresses concerns of contemporary globalization, diversity, and the intercultural nature of communication today. With the rapid flows of peoples, cultures and media across national borders, many social settings have become linguistically and culturally diverse. As people from such diverse backgrounds meet face-to-face or in online contexts, their meeting becomes a site for an intercultural encounter where they negotiate meanings, social identities, and power relations. The field of language education in particular is impacted by this diversity in a number of ways. For example, second language teacher education courses inevitably must deal with new notions of culture as well as which cultures to teach and how to teach them. Language professionals in particular should seriously reconsider how the issues of culture are represented in teaching materials and addressed in classroom practices. Keeping this in mind, the book approaches the notion of intercultural communication primarily as a communicative practice. The chapters present theoretical concepts and empirical cases of intercultural communication from a wide range of social contexts such as family, workplace, business, and education. This then naturally leads English teachers to ask questions about the role of culture in language teaching. Questions such as these are of paramount importance: how to teach culture in second language classrooms, how cultures of the self and others are represented in teaching materials such as textbooks, and how they are addressed in classroom practices, and how intercultural learning is assessed by second language teachers.

This book addresses concerns of contemporary globalization, diversity, and the intercultural nature of communication today. With the rapid flows of peoples, cultures and media across national borders, many social settings have become linguistically and culturally diverse. As people from such diverse backgrounds meet face-to-face or in online contexts, their meeting becomes a site for an intercultural encounter where they negotiate meanings, social identities, and power relations. The field of language education in particular is impacted by this diversity in a number of ways. For example, second language teacher education courses inevitably must deal with new notions of culture as well as which cultures to teach and how to teach them. Language professionals in particular should seriously reconsider how the issues of culture are represented in teaching materials and addressed in classroom practices. Keeping this in mind, the book approaches the notion of intercultural communication primarily as a communicative practice. The chapters present theoretical concepts and empirical cases of intercultural communication from a wide range of social contexts such as family, workplace, business, and education. This then naturally leads English teachers to ask questions about the role of culture in language teaching. Questions such as these are of paramount importance: how to teach culture in second language classrooms, how cultures of the self and others are represented in teaching materials such as textbooks, and how they are addressed in classroom practices, and how intercultural learning is assessed by second language teachers.