Presented by: Ashok Raj Khati

In this blog post, we have attempted to present a broader picture of writing practice in English Language Education (ELE) programs in Nepali universities. The interaction is focused on how the ELE/ELT (English Language Teaching) programs in Nepali universities are guided by the policy provision and the initiations that have been taken to boost up writing skills of the students. The interaction incorporates the current practices as well as the challenges to develop academic writing of the students. Furthermore, the participants opine in relation to the publication practices of the faculty members and the issue of plagiarism in relation to their ELE/ELT programs of the university.

Let me introduce the participants of this interaction.:

- Laxman Gnawali, PhD– Associate Professor and the coordinator of ELE/ELT program, school of education, Kathmandu University Nepal.

- Laxmi Prasad Ojha– Lecturer at the department of English education, faculty of education, Tribhuvan University Nepal.

- Bishnu Kumar Khadka- the chairperson of English subject committee, faculty of education, Mid-Western University Nepal.

- Janak Singh Negi- Lecturer at Manilek Multiple Campus, a proposed constituent campus, Far Western University Nepal.

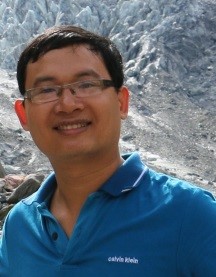

- Uttam Gaulee, PhD– Assistant Professor at Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland Area, the USA.

Dr. Gaulee provides his opinions concerning Nepali Universities based on his long experience of working in Nepal, general observation and his academic collaborations with these universities in different ways.

Can you please share any good initiations to develop writing skills of students in ELE/ELT program in the University you are involved?

Dr Laxman Gnawali: We have a strong focus on academic writing development in the graduate programs. For both MEd and MPhil programs, we have formal credit courses. These courses give theoretical understanding as well as practical exposure to develop students’ writing skills. We start with the basics such as paragraph writing, move on to a five-paragraph essay, and later to thematic paper as well as research paper writing. The culmination is the thesis writing in which they fully actualize their academic writing skills.

Dr Laxman Gnawali: We have a strong focus on academic writing development in the graduate programs. For both MEd and MPhil programs, we have formal credit courses. These courses give theoretical understanding as well as practical exposure to develop students’ writing skills. We start with the basics such as paragraph writing, move on to a five-paragraph essay, and later to thematic paper as well as research paper writing. The culmination is the thesis writing in which they fully actualize their academic writing skills.

Mr Laxmi Prasad Ojha: I have seen a positive sign by including research and writing as the integral part of the curricula in my university. This is encouraging step towards developing students with reading, writing and critical thinking abilities. Most courses in Bachelor’s and Master’s degree includes writing as an essential part of curricula and evaluation system. Students are supposed to write essays, narratives, reflections, research reports, research papers, book reviews, analytical writing at graduate and undergraduate levels and the thesis writing in the graduate level despite the fact that we have not been able to deliver the courses very well.

Mr Laxmi Prasad Ojha: I have seen a positive sign by including research and writing as the integral part of the curricula in my university. This is encouraging step towards developing students with reading, writing and critical thinking abilities. Most courses in Bachelor’s and Master’s degree includes writing as an essential part of curricula and evaluation system. Students are supposed to write essays, narratives, reflections, research reports, research papers, book reviews, analytical writing at graduate and undergraduate levels and the thesis writing in the graduate level despite the fact that we have not been able to deliver the courses very well.

Mr Bishnu Kumar Khadka: We formed an ELT club of the students studying in English language education with the support of some international scholars. The journey of writing begins with writing meeting minutes which generally includes the name of the attendees, agenda, discussion and decisions in English. Furthermore, members of the club write and share their experiences and new insights they found during the study. In our semester-based system in Mid-Western University, students write assignments, project-based reports, review reports and research reports. The system generates the writing as a process during the whole semester as well as a part of the evaluation. When we felt a few challenges to gear up writing on the part of students, we established the Writing Center in the University with support of some international scholars. The center started webinar, training of teachers facilitated by scholars from the USA. It is really an inspiring move for us to develop writing in the English language.

Mr Bishnu Kumar Khadka: We formed an ELT club of the students studying in English language education with the support of some international scholars. The journey of writing begins with writing meeting minutes which generally includes the name of the attendees, agenda, discussion and decisions in English. Furthermore, members of the club write and share their experiences and new insights they found during the study. In our semester-based system in Mid-Western University, students write assignments, project-based reports, review reports and research reports. The system generates the writing as a process during the whole semester as well as a part of the evaluation. When we felt a few challenges to gear up writing on the part of students, we established the Writing Center in the University with support of some international scholars. The center started webinar, training of teachers facilitated by scholars from the USA. It is really an inspiring move for us to develop writing in the English language.

Mr Janak Singh Negi: Apparently, there are some good initiations. It is because writing courses have been taught at the university level. I know these courses touch some practical aspects of academic writing, but most of the students do not seem practicing writing except writing Master’s thesis at the end of the program in this region.

Mr Janak Singh Negi: Apparently, there are some good initiations. It is because writing courses have been taught at the university level. I know these courses touch some practical aspects of academic writing, but most of the students do not seem practicing writing except writing Master’s thesis at the end of the program in this region.

Dr Uttam Gaulee: In the USA, there is a saying, “put your money where your mouth is.” In Nepali universities, teachers are given money to grade student papers but not for providing feedback. Providing incentives for students to write and for teachers to provide feedback more frequently would help. I see that Mid-Western University has now established a writing center. I think this is a good beginning.

Dr Uttam Gaulee: In the USA, there is a saying, “put your money where your mouth is.” In Nepali universities, teachers are given money to grade student papers but not for providing feedback. Providing incentives for students to write and for teachers to provide feedback more frequently would help. I see that Mid-Western University has now established a writing center. I think this is a good beginning.

What are the best practices for developing writing skills of students?

Dr Gnawali: Formal lessons in which students get engaged in writing and peer feedback followed by tutor feedback are common practices. Our process is from simple to complex. We encourage students not only to write papers as assignments but also to restructure, if needed, the same and submit to the national and international journals. Many papers get published in peer reviewed journals. We also encourage students to present the same papers in the conferences. The conference presentation itself may not help writing but as the students work harder when they plan for the conferences, their papers get better. In order to inject the latest development in academic writing, we organize academic writing workshops led by international facilitators having expertise in academic writing.

Mr Ojha: After the introduction of the semester system, we have been able to engage our students in various writing projects such as book reviews, reflective essays, narrative reports which helped the students develop writing skills. The effort gradually enabled students to develop writing academic and research papers. Some students pursuing their Master’s in ELT program at Tribhuvan University can produce some coherent pieces of academic papers. We have regular conferences with students, we organize seminars and workshops in academic writing, we provide focus on giving feedback to students’ write-ups and encourage them to attend conferences and present there. We also encourage and help them to write for different ELT related magazine and journals. These days, they are able to write theses with better academic writing and research skills due to the constant feedback they receive from their tutors while writing the assignments for various courses.

Mr Khadka: To encourage the writing of students, I created a Facebook group for them to raise questions, generate discussion, and write on different academic issues. Students actively participate in the discussion and they write reflective notes on their experiences which I found very effective both for classroom purposes and developing writing skill.

Mr Negi: Regarding the best practices, I think, it depends on whether you are talking about theoretical or practical aspects. If we look at the theoretical aspects, over the last few years there is drastic change in the university course; some course on academic/creative writing e.g. Academic Writing, Creative Writing in ELT, Advance Academic Writing to name only a few have been introduced in Bachelor’s and Master’s programs, where students get the opportunities to enhance their academic and creative writing skills. But, if we look at the practice side of these skills, rather different scenario comes in the mind i.e. some students know about academic/creative writing. However, most of them cannot write academically and creatively.

Dr Gaulee: Apart from sporadic one or two-day workshops, etc., I am not aware of a good writing development program functioning in a Nepali university so far. I wish I am wrong. I think writing is probably not yet understood as a process that can be developed with the continuous effort with proper feedback. I think there is an opportunity in the universities to make students aware of writing steps and allow them to practice pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing. Teachers need to provide appropriate feedback to students depending on where they are struggling. Students typically are not given a proper reason to write other than to sit for the nightmarish high-stake year-end exams.

What are the challenges to enhance writing practices of the students?

Dr Gnawali: The major challenge is that the most students join the program with no experience of writing anything except in the examination. They have issues with the grammar, vocabulary and generating ideas. So, starting from the scratch is very challenging. As they have not had any experiences in sustained writing, it’s challenging to get them to write longer texts in the beginning.

Mr Ojha: I think the most important challenges are a large number of students (large class size) in my department. It is really challenging to support, mentor and provide feedback at the personal level to help them develop writing skill. The knowledge and skill of the faculty members involved in higher education is another real challenge as most of them are involved in teaching without any prior academic and professional background or training on academic writing. Therefore, if we want to introduce research and academic writing in our higher education, we have to groom our teachers to be able to mentor their students.

Mr Khadka: In my experience, writing, either in mother tongues or any other languages, is considered as a tough and the most reluctant task in our context for the beginners or advanced level language learners. Students do not feel comfortable in writing. I have experienced that many students‘copy and paste’ from the internet-based resources to complete the assignments and meet the deadlines in the university. Therefore, it is highly challenging to foster the culture of original, cohesive and purely academic writing in our cases.

Mr Negi: This is really an interesting question. The big challenge is to put theory into practice i.e. making students write academically or creatively instead of knowing or writing about academic or creative writing. Most of the students spend their time preparing for the examination and in the examination, they are asked questions like these: “What are the 5R techniques for summarizing the paragraph?” instead of “Read the following paragraph and summarize it”. “What do you mean by invention techniques for generating ideas?” instead of “Generate the ideas for writing an essay on the following topic/s…”. “What are the characteristics of poetry?” instead of “Write a poem (for example, a sonnet, a free verse, Gajal, haiku…). I mean the evaluation system, in general, itself is a challenge for better learning output. If students are taught, for example, to summarize or to write a poem they should be able to do so and the same should be tested in the examination. If not, they know/memorize few lines about academic or creative writing but will not be able to write academically or creatively.

Dr Gaulee: I think one of the major challenges is large classes. The teachers should be able to coach a student to develop writing skills. The second major challenge is the lack of teacher training on how to successfully serve as a coach for their students toward developing writing.

What about the publications practices of faculty members involved in the program?

Dr Gnawali: Publication is a regular feature of the faculty here at Kathmandu University. Every faculty publishes at least one paper each year in national or international journals. We also have our own journal, Journal of Education and Research which is edited by the faculties. They develop their own expertise in course of editing and publishing process. Some senior faculties are editors and reviewers for the peer reviewed journals.

Mr Ojha: In general, we have been doing fairly well in research and publication in the recent times. Some of the faculty members (for example the Head of Department, Dr Prem Phyak) have really been inspirational both in terms of number and quality of publications in high standard journals. The faculty members are collaborating with each other to research, write and deliver presentations in the seminars and conferences. This is certainly a good indication of collaborative academic and professional growth. We are also planning to publish a journal on ELT and Applied Linguistics from our department so that the faculty members from various institutions can get support and space for the publication of their research works. Some senior colleagues are also mentoring the young faculty through collaboration, review and resources.

Mr Khadka: Regarding the publication of the academic journal, I coordinated the publication of ‘Journal of Education Science’ (JOES) in the capacity of Editor-in-chief, the first volume in the university in 2012. In the volume, there are contributions of faculty members and students. We are planning to publish another volume very soon. Likewise, we encourage the students to publish the journal with their own initiation. Faculty members and students are also collaborating with the Journal of NELTA Surkhet in term of participating in the workshop in writing and contributing to the volume.

Mr Negi: Currently the interest in publishing academic work in academic or research journals is growing very fast. Most of the colleges and departments have started publishing some academic journals and Souvenir in the region where both students and teachers have opportunities to publish their academic and creative works. Some ELT professionals have started writing for national and international academic journals and are really engaged in academic publications. However, it is yet to meet the standards as the most articles by the faculty members seem a mere elaboration of the classroom notes. They lack a broad study on academic and ELT related issues.

Dr Gaulee: While writing has always been encouraged – probably ideally, it is only recently that universities are giving more emphasis in publications, which is certainly a good sign. Research, writing, and publications have been more of an exception than the norm so far, which needs to be changed with the recent growth of publication avenues, access to resources and networks of professionals via scholarly societies and conferences.

What are your thoughts on plagiarism- an issue in the Nepali higher education?

Dr Gnawali: There have been publicly discussed issues on plagiarism in higher education. University Grants Commission has had some cases of plagiarism with the University faculties. Colleges that run foreign University programs have faced the issues with their students for plagiarizing papers/assignments. I believe that there are some major reasons for scholars to plagiarize. There are some cases that authors have intentionally plagiarized with an intention to get a quick promotion. The key reason is that there is no proper training and awareness raising on how not to plagiarize. Authors refer but either they do not know how to properly give credit to the original author. Likewise, the regulations are not fully enforced, and when someone is found guilty, they are not penalized.

Mr Ojha: Plagiarism is a serious issue in Nepali academia. The motivation of the students to pursue higher education is an important factor to influence how they write their papers and theses. Many of them are not even aware of the issues related to plagiarism. Moreover, we do not have any system (e.g. digital repository of the theses submitted and the software) to track malpractices like plagiarism. It is not possible for a professor to track the plagiarized papers, assignments and theses of the student/s. Hence, it is important to develop awareness on maintaining ethics in research and writing through training and other possible ways.

Mr Khadka: It is a serious issue in the higher education in Nepal – very difficult to speak out for me. So, there is a blaming culture in our context regarding plagiarism. The writers in this university are not the exception. Students often submit highly plagiarized papers and research reports, not intentionally, but because they do not know how to avoid plagiarism. However, in Nepali universities, few so-called academicians, writers and researchers do it deliberately for different purposes. Therefore, it is a high time to be well informed by ourselves (faculty members) and guide our students in the university accordingly to avoid plagiarism.

Mr Negi: Oh! This is the most interesting query above all! Ashok Ji, if you read the course books on academic writing itself written by some Nepali authors, the definition of plagiarism itself is plagiarized. Very honestly, this is not my criticism to particular authors but it is the ground reality. The plagiarized case of Master’s thesis has already been disclosed in various print media. So, I do not need to elaborate it further. It means we know plagiarism. However, some of us still plagiarize and our plagiarized work is accepted; nobody (even some academicians in authority) raises questions on it seriously, so we (some academic practitioners) neither realize nor make somebody realize the impacts of plagiarism. Therefore, to control and check plagiarism to some extent, we need to have at least a plagiarism checking software in our colleges or departments. My point is plagiarism should be avoided at any cost.

Dr Gaulee: In the lack of proper writing development in place, plagiarism in Nepali higher education is still a “white crime.” It sometimes serves as a fodder for blame game or even political ammunition. Either way, it has not been addressed in a way that it should.

Would you like to add anything about the writing practices at the end?

Dr Gnawali: To be honest, academic writing has not been established as a culture in Nepalese education scenario. Therefore, we need to revamp academic writing practices from the school level to the university.

Mr Ojha: We still lack adequate research and writing culture in Nepali academia which negatively affects the students and faculties in a long run. To be frank, we have not been able to give enough space to write in our university courses especially the academic writing skills. I think it is high time to introduce academic writing as a compulsory course in all disciplines including ELT program and deliver them following mentoring model. The university department and colleges can also establish writing centers where students can receive support from the mentors.

Mr Khadka: In my view, we must discourage ‘copy and paste’ culture. Hence, there is much to do in academic writing in the university.

Mr Negi: In fact, we are floating on the surface with motionless motion, we are not anchored academically; we are more formal and still practicing much with formality. Let’s try to be more practical and realistic.

Dr Gaulee: Status quo needs to change. In universities, writing centers need to be established, an intensive educational plan should be implemented, which may need a great deal of willpower on the part of leadership to facilitate awareness, planning, and implementation, which will involve expertise, training, money and patience.

We thank our valued participants for generating this ELT Choutari interaction. We will come up with the further discussion and writings on the “Writing” based on these valuable ideas and opinions in our upcoming issues. For now, ELT Choutari opens the discussion forum for you to share your thoughts after reading the ideas of our contributors. Please share your thoughts in the comment boxes below.

Ashok Raj Khati is one of the editors of ELT Choutari. He writes for academic journals, ELT blogs and Nepali national dailies.

Like this:

Like Loading...

examination paper. Teachers often provide them notes on the contents and students copy them in their note books. When teachers ask them to be prepared for classroom writing, they remain absent in the class. When they are asked to write, they copy from bazaar notes, they do not make attempt of their own. They fear of being commented upon their writing. Teachers also do not encourage students to write. Teachers are mostly found writing in social media about the contemporary issues but academic writing is most neglected area in this region.

examination paper. Teachers often provide them notes on the contents and students copy them in their note books. When teachers ask them to be prepared for classroom writing, they remain absent in the class. When they are asked to write, they copy from bazaar notes, they do not make attempt of their own. They fear of being commented upon their writing. Teachers also do not encourage students to write. Teachers are mostly found writing in social media about the contemporary issues but academic writing is most neglected area in this region.

Dr Laxman Gnawali: We have a strong focus on academic writing development in the graduate programs. For both MEd and MPhil programs, we have formal credit courses. These courses give theoretical understanding as well as practical exposure to develop students’ writing skills. We start with the basics such as paragraph writing, move on to a five-paragraph essay, and later to thematic paper as well as research paper writing. The culmination is the thesis writing in which they fully actualize their academic writing skills.

Dr Laxman Gnawali: We have a strong focus on academic writing development in the graduate programs. For both MEd and MPhil programs, we have formal credit courses. These courses give theoretical understanding as well as practical exposure to develop students’ writing skills. We start with the basics such as paragraph writing, move on to a five-paragraph essay, and later to thematic paper as well as research paper writing. The culmination is the thesis writing in which they fully actualize their academic writing skills. Mr Laxmi Prasad Ojha: I have seen a positive sign by including research and writing as the integral part of the curricula in my university. This is encouraging step towards developing students with reading, writing and critical thinking abilities. Most courses in Bachelor’s and Master’s degree includes writing as an essential part of curricula and evaluation system. Students are supposed to write essays, narratives, reflections, research reports, research papers, book reviews, analytical writing at graduate and undergraduate levels and the thesis writing in the graduate level despite the fact that we have not been able to deliver the courses very well.

Mr Laxmi Prasad Ojha: I have seen a positive sign by including research and writing as the integral part of the curricula in my university. This is encouraging step towards developing students with reading, writing and critical thinking abilities. Most courses in Bachelor’s and Master’s degree includes writing as an essential part of curricula and evaluation system. Students are supposed to write essays, narratives, reflections, research reports, research papers, book reviews, analytical writing at graduate and undergraduate levels and the thesis writing in the graduate level despite the fact that we have not been able to deliver the courses very well. Mr Bishnu Kumar Khadka: We formed an ELT club of the students studying in English language education with the support of some international scholars. The journey of writing begins with writing meeting minutes which generally includes the name of the attendees, agenda, discussion and decisions in English. Furthermore, members of the club write and share their experiences and new insights they found during the study. In our semester-based system in Mid-Western University, students write assignments, project-based reports, review reports and research reports. The system generates the writing as a process during the whole semester as well as a part of the evaluation. When we felt a few challenges to gear up writing on the part of students, we established the Writing Center in the University with support of some international scholars. The center started webinar, training of teachers facilitated by scholars from the USA. It is really an inspiring move for us to develop writing in the English language.

Mr Bishnu Kumar Khadka: We formed an ELT club of the students studying in English language education with the support of some international scholars. The journey of writing begins with writing meeting minutes which generally includes the name of the attendees, agenda, discussion and decisions in English. Furthermore, members of the club write and share their experiences and new insights they found during the study. In our semester-based system in Mid-Western University, students write assignments, project-based reports, review reports and research reports. The system generates the writing as a process during the whole semester as well as a part of the evaluation. When we felt a few challenges to gear up writing on the part of students, we established the Writing Center in the University with support of some international scholars. The center started webinar, training of teachers facilitated by scholars from the USA. It is really an inspiring move for us to develop writing in the English language. Mr Janak Singh Negi: Apparently, there are some good initiations. It is because writing courses have been taught at the university level. I know these courses touch some practical aspects of academic writing, but most of the students do not seem practicing writing except writing Master’s thesis at the end of the program in this region.

Mr Janak Singh Negi: Apparently, there are some good initiations. It is because writing courses have been taught at the university level. I know these courses touch some practical aspects of academic writing, but most of the students do not seem practicing writing except writing Master’s thesis at the end of the program in this region. Dr Uttam Gaulee:

Dr Uttam Gaulee:

This book addresses concerns of contemporary globalization, diversity, and the intercultural nature of communication today. With the rapid flows of peoples, cultures and media across national borders, many social settings have become linguistically and culturally diverse. As people from such diverse backgrounds meet face-to-face or in online contexts, their meeting becomes a site for an intercultural encounter where they negotiate meanings, social identities, and power relations. The field of language education in particular is impacted by this diversity in a number of ways. For example, second language teacher education courses inevitably must deal with new notions of culture as well as which cultures to teach and how to teach them. Language professionals in particular should seriously reconsider how the issues of culture are represented in teaching materials and addressed in classroom practices. Keeping this in mind, the book approaches the notion of intercultural communication primarily as a communicative practice. The chapters present theoretical concepts and empirical cases of intercultural communication from a wide range of social contexts such as family, workplace, business, and education. This then naturally leads English teachers to ask questions about the role of culture in language teaching. Questions such as these are of paramount importance: how to teach culture in second language classrooms, how cultures of the self and others are represented in teaching materials such as textbooks, and how they are addressed in classroom practices, and how intercultural learning is assessed by second language teachers.

This book addresses concerns of contemporary globalization, diversity, and the intercultural nature of communication today. With the rapid flows of peoples, cultures and media across national borders, many social settings have become linguistically and culturally diverse. As people from such diverse backgrounds meet face-to-face or in online contexts, their meeting becomes a site for an intercultural encounter where they negotiate meanings, social identities, and power relations. The field of language education in particular is impacted by this diversity in a number of ways. For example, second language teacher education courses inevitably must deal with new notions of culture as well as which cultures to teach and how to teach them. Language professionals in particular should seriously reconsider how the issues of culture are represented in teaching materials and addressed in classroom practices. Keeping this in mind, the book approaches the notion of intercultural communication primarily as a communicative practice. The chapters present theoretical concepts and empirical cases of intercultural communication from a wide range of social contexts such as family, workplace, business, and education. This then naturally leads English teachers to ask questions about the role of culture in language teaching. Questions such as these are of paramount importance: how to teach culture in second language classrooms, how cultures of the self and others are represented in teaching materials such as textbooks, and how they are addressed in classroom practices, and how intercultural learning is assessed by second language teachers.