Abstract

The paper entitled “English as a medium of instruction in public schools of Nepal: practical consideration” aims to explore the teachers’ perceptions regarding EMI in community schools and to find out the practicality of EMI in Community schools of Nepal. The interview was used as a tool for data collection, five teachers teaching in public schools where English was used as the medium of instruction were selected purposively. It was found that practically public schools are shifting to the English medium though it was challenging to apply. It was the demand of parents and students as well as the time. Public schools were found using EMI to create better job opportunities for the students, parents’ requests, to increase the number of students in the school, and because of the government policy practically.

Background of the study

The teachers appointed 15/20 years before are still in service and are compelled to teach in English medium classes in public schools. It is not an easy task for them because they were not taught in English at their time. It becomes difficult for them to make the student understand the content because they cannot understand it correctly. EMI is not a difficulty for aged teachers, but it’s becoming a problem the newly appointed teachers too. It’s in the sense that every subject except Nepali is being taught in English medium. While teaching social studies, typical Nepali words like gundruk, dhido, dhiki, janto, chhatri etc., are romanized. I think it is straightforward for them to understand the terms in the Nepali language.

Nepal is a developing country, and education in remote areas is very pitiful. The children are not getting education facilities in their own mother tongue for many reasons like lack of teachers, textbooks, difficulty getting to school and so on. In such circumstances teaching in English medium is a complicated job.

Nepal is a multilingual country. Many ethnic groups have their mother tongue and acquire their native language as their first language. There are still such people who don’t know the Nepali language. For example, in the Magar community, only the Magar language is spoken, and they are unaware of the Nepali language. In addition, the government has also declared that children have the right to get education in their mother tongue up to the primary level. On the other hand, English medium education is prioritized by the government and contemporary society.

Consequently, the planning and policy of the country, the necessity of the society, and teacher conditions do not match, and the quality of education is declining daily in our country. The plan makers do not observe the actual context of the country. They only make the plan by targeting the area where they stay, i.e., the city. In all this, the students are suffering. It means the nation is at a loss because it will lack human resources and cannot step towards development with no good human resources.

EMI is one of the burning issues in the teaching field of Nepal. The constitution has declared the right to education in the children’s mother tongue. Instead, the children are forced to take instruction in the English Language directly and indirectly. The hegemony of the English Language indirectly forces parents to admit their children to the school where English is used as a medium of instruction.

I am also a parent. I sent my daughter to a Montessori school (private school), and I used to teach in a government school simultaneously. When I compared both schools’ delivery, I did not find vast differences between them. Instead, I found a more experienced teacher in my community school. So I decided to take my child to the same school where I was teaching. I took suggestions from some of my friends, who suggested I shouldn’t take my child to the community school to make a base in English. But I believe that a child should learn the subject matter properly and they can learn the language through different means like TV, Internet.

Some teachers believe that the student must be taught the content and that the language doesn’t matter. In contrast, the school administration is forcing teachers to teach in English. Even parents are also conscious of the English medium. They think fluency in English means their children are talented in their studies, but knowing English is not talent in the subject area. So I found EMI as an issue in the educational field. Some believe EMI is a better way of teaching. On the other hand, some favor focusing on subject matter rather than language. So I want to explore different teachers’ views on whether English should be used as a medium of instruction or concentrate on the content.

Objectives

The objective of the study was to explore the teachers’ perceptions and practices of EMI in community schools.

English as a Medium of Instruction

English is the most widely spoken language in the world. It greatly influences the education system of most countries in the world. It is taught as the subject and used as the medium of instruction to teach other issues too. English Medium Instruction (EMI) refers to teaching academic subjects in English in non-Anglophone countries ( Macaro & et al. 2016). It is believed that if the subject matter is taught in English, it helps improve the children’s language because of the greater exposure. EMI is a model of teaching in which non-English subjects are taught through the medium of English (Poudel, 2021). Teachers use the English Language to elaborate the content. EMI is the regular practice in private schools. Community schools also follow this trend because of the parents’ attraction to the English Language.

English Language in school for teaching purposes is preferred because it may develop the listening and speaking skills of the students.EMI might help the students to increase their vocabulary power too. Tran et al. (2021) stated that students’ knowledge of technical terms was believed to be improved most through EMI by both lecturers and students.

Nepal is a multilingual country. More than 129 languages are spoken in Nepal. The government has declared that every child has the right to get education in their mother tongue up to the primary level. Contrary to this, children are forced to learn in English, a non-native Language for Nepalese learners. Regarding the instruction medium, Nepal’s constitution (2015) declared that Nepali or English, or both languages, can be used in the classroom.

Challenges of EMI

Teaching learning itself is a challenging job. Many learners feel difficult to understand the subject matter because of the language used to teach them in the class. Children from most ethnic groups learn Nepali as their second language. So, they may feel uneasy about learning using the English language as the medium of instruction. The class can be less interactive and silent. There may be a communication gap between teachers and students because of the language problem. EMI is not only a problem for the learner; it may also be difficult for the teachers. Bista (2011) views that educational institutions may not have language learning labs, the computers and internet use may be limited. Enough audio and visual aids may not be in the class, and textbooks and resources materials may be challenging. Teachers teaching may not have sufficient knowledge of the English language, which may lead the children to a misconception of the English language. Khatri (n. d.), English as a medium of instruction like students’ weak exposure to the English language, mother tongue interference in the classroom, poor competence of students in English, lack of support and encouragement from the parents and society, and no motivating environment for the teachers and schools are not resourceful and well facilitated.

Popularity of EMI

English is a powerful language in the world. It is the dominant language. Learning the English Language is a kind of indirect compulsion for the learner. Tang (n.d.) stated that language improvement is essential for EMI implementation. People without English are partly literate because English is mandatory in every sector. For example, one should know English to use an ATM, English is necessary to use email internet and get a job abroad, and fluent English speaking skills, which is equally essential in tourism. No sector is untouched by the English Language. Parents are keenly interested in teaching English to their children in Nepal for a secure future for their children.

The English language is used as the language of teaching and learning too. English is taught as a compulsory subject from pre-primary to university level in Nepal. The requirement to be a primary teacher in Nepal was SLC passed, who still teach in schools. In government schools, only one English subject used taught in the contemporary period. Public school teachers who are unfamiliar with English languages are compelled to teach in English. We believe that the more practice, the more perfection. It means that to make EMI effective, the learners and the teachers must use the English Language as much as possible.

In contrast, it is not practical because of many factors such as the influence of mother tongue, affective filter, lack of English-speaking environment, etc. Khatri mentioned in his research that there is no encouraging environment in the schools for practicing EMI-supported instructional activities in the regular pedagogy. Furthermore, he explained that according to the participant of his study, there is no English-speaking environment around their school premises.

Bista (2011) researched Teaching English as a Foreign/Second Language in Nepal: Past and Present. The main objective of the research was to review the history of English language teaching English as a second or foreign language in schools and colleges in Nepal. The author used secondary sources to complete his study as it was library-based. He concluded that the educators were using traditional lectured and grammar-translation methods, which is continuing. Furthermore, he explored that English language teaching is challenging because of the lack of physical and technical facilities.

Khatri (n. d.) studied the topic of Teachers’ Attitudes toward English as a Medium of Instruction. The research objective was to explore the teachers’ attitude towards using EMI in public schools and the challenges they faced in adopting EMI. The research was conducted using the mixed method. The results of the study revealed that public school teachers were aware of the basic concept of the notion of English as a medium of instruction. They were found positive in implementing EMI in conducting their daily teaching and learning activities.

Tang (n. d.) accomplished his research on the Challenges and Importance of Teaching English as a Medium of Instruction at Thailand International College. The core objective of the study was to explore the challenges of teaching English as a medium of instruction (EMI) and its essential impact on Thailand International College. A qualitative method was employed, utilizing an interview protocol as a research instrument. The outcome discovered four categories of challenges: linguistic, cultural, structural, and identity-related (institutional) challenges and four essential aspects of EMI implementation, namely, the importance of language improvement, subject matter learning, career prospects, and internationalization strategy.

Dearden (2014) researched ‘English as a medium of instruction – a growing global phenomenon.’ This study was designed to determine the size, shape, and future trends of EMI worldwide. She reported her research findings within five main points: the growth of EMI as a global phenomenon on EMI, official policies and statements on EMI, different national perspectives on EMI, public opinion on EMI, and teaching and learning through EMI. The main conclusions of the study were general trend is towards the rapid expansion of EMI provision; there is official governmental banking for EMI but with some interesting exceptions and so on.

Methods of the study

I used qualitative research design in this research, using both primary and secondary data sources. My study population was the teachers who were teaching other subjects rather than English. Five teachers were purposively selected from five public schools of Vyas Municipality, Tanahun where the English language was used as a Medium of Instruction (EMI). I took interviews with the teachers to collect data.

Data analysis and interpretation

This section is mainly concerned with analyzing and interpreting the information from the interview and observation with the different participants. Participants’ views are discussed and interpreted, developing different subthemes.

Teachers’ perceptions toward EMI in community schools

The teachers’ perceptions of using EMI in public schools are discussed and interpreted, developing the following themes based on their perceptions.

Use of the English language inside classroom

Many community schools have adopted English as the medium of instruction for many reasons. The teachers are compelled to teach in English whether they are competent. People say that, though the English Language is used to teach in the community schools, the result is unsatisfactory. Students’ performance in community schools is not good compared to private schools. So to understand the reality, I asked my participants about using English inside the classroom.

I asked my participant whether the teachers use only English Language inside the classroom. In this regard, my first participant Mr. Jagat said that Teachers use the English Language to teach but use the Nepali Language to explain the text because most students may not understand the subject matter in the English Language.In the same way, another participant, Mrs. Mamata, stated that I translate the content into Nepali to make it easier for the students. I could read their face though they don’t ask me to explain in Nepali. Regarding this question, my third participant Mrs. Sita shared her view. The teacher has to use both languages i.e., English and Nepali, to make the students clear about the content. Students are not able to understand the subject matter only in English.

Here my participants’ ideas are similar to Shah’s (2019) views that teaching in English seems a formality and a way of attracting students to schools. After analyzing the opinions of my participants, I understood that the community schools are using English only for formality. English language used as the medium of instruction is not practical because the students cannot understand the content in the English language. As a result, teachers use both English and Nepali Language in the classroom.

English medium for further study

After completing the secondary level, the students must choose a specific subject for their studies. Science and other technical subjects are being taught in English. The materials are also available in English. So the students must know the English Language. If they feel easy to use the English language, they will do better in technical subjects. Otherwise, they have to choose other subjects instead of being interest in studying such subjects. Here, my fourth participant, Mr. Dinesh, stated: English language is helpful to those students who are interested in a technical subjects. It helps the students to secure a good positions. Similarly the next participant, Mrs. Sita, claimed that English is essential for students to go abroad for higher study. It is impossible to go to the UK, the USA, and Australia for higher studies without the knowledge of the higher studies.

The English language has its influence in every sector. Likewise, education sector has also been dominated by the English Language. The English language is one of the main criteria to be fulfilled by students who want to study technical subjects. Furthermore, it is compulsory to acquire good scores on English language tests like TOEFL, IELTS, GRE, etc. to get admission to college and university abroad. Bista (2011) has claimed that, not only high school graduates but also college graduates prefer improving their level of English to pursue either higher study abroad or to start a job in foreign setting. It is a fact that the English Language helps students in their further study because at a higher level. However, students are reading in Nepali Medium taking Nepali as their major subject, they have to face the questions of compulsory subjects in English medium in board examinations. In this case, EMI at the school level may be helpful to them to understand the English Language somehow.

Strategy to increase students number

The parents’ attraction to teach their children English Language leads them toward boarding school. So the number of students in a community schools is decreasing daily. Many children are sent to the private English schools by buses. Those schools are far from from their homes, and they have to pay expensive fees but the community schools are searching students. The reason might be the community schools do not focus on English as medium of instruction earlier. However, nowadays, most community schools are also using books printed in English language and teach using English as medium of instruction. So, the number of students are being increased in public schools as well. While I asked teachers, they stated that the community schools have no other option to increase students. In this case, my first participant Mr. Jagat shared that;

The community schools do not have enough required human resources to teach in the English medium, but the teachers are compelled to teach in English medium because the school administration has made the strategy. The administration believes that if they teach in English, the parents would send their children to the community school.

In the same way, my next participant Dinesh said Before the implementation of EMI, we had a very low number of students. But when we started to use books in English medium of private publication, the number of students increased gradually When the same question asked to another participant Mrs. Sita, she stated: Previously, most of the students from her locality were sent to private schools. It was because private schools used to provide education in English. So our school management committee, PTA, and the school administration also decided to apply EMI in our school to increase the number of students.

The answers of the different teachers on the same query advocated that the community school must implement the English medium to increase the number of students in school. Bista (2011) claimed that the trend of sending children to English medium schools and or colleges have begun as an English mania today in Nepal. The majority of parents like to send their children to English-speaking schools. The decreasing number of students is a major problem in community school in the present day. The leading cause of this problem is quality education. The parents believe that the school where English is taught provides quality education. So they sent their children to private school. That’s why the community school has to choose EMI to attract the parents’ attention towards community school and increase number of students.

Teachers’ practice in EMI

The teachers are the main character to apply the policies of education in a real field. So, I observed few classes of public schools taking consent from the the suthorities and the teachers where English medium was used as classroom instruction. Mainly, I observed the classes other than English, where English was used as medium of instruction to find the practicality of the EMI in public schools.

Use of translation method for teaching

I went to Shree Janamaitri Secondary School of Vyas Municipality (name changed), a renowned school in Nepal. I entered into class seven, section D. The students stood up and greeted me. The teacher was teaching the subject matter of social studies as it is written in the book and was trying to explain it in English. She noticed that the students were not clear about the topic, so, she described in Nepali language. When the teacher asked the questions in English, most of the students feel easy to answer in Nepali except for some. The teacher asked the meaning of the word vaccination then the students replied, ‘Khop Launi’. Likewise, they responded in Nepali that the word Avoid means ‘Rokne,’ settlement, Basobas Garne. The teacher herself used the word’ DhamiJhakri’ because the exact English word to replace the word is not available in the English language.

Similarly, I visited the second school, Shree Janajagriti Secondary School (name changed). The school was in the countryside. The school was also practicing the EMI. I observed class six where a teacher was dealing with social studies. Students greeted me in English and responded. They had the books written in English language. The teacher was reading the book and translating the lines in Nepali to make the students clear about the content. The teacher asked the questions in English, but the students replied in Nepali. It seems that they understand the English language, but feel easy using the Nepali Language while responding.

The third school I visited was Shiddhivinayak Secondary School (name changed). The class I observed was class 9, and the teacher was teaching Mathematics. The topic was construction. The teacher was trying to make the students clear about constructing rectangles. I found that the book was written using English language but the teacher was using the Nepali Language to explain the matter. The students were also asking questions in Nepali, and the teacher was answering them in the Nepali Language too.

Less interaction using English

I visited a couple of schools to observe the practicality of the English Language. When I entered the first school for class observation, it was quarter to ten, and the students gathered on the ground for the Morning Prayer. I waited for a while, and found that the language to perform the assembly was Nepali, not English. One of the teachers asked me in Nepali,’ KATI KAMLE AAUNU BHAYO?’ I thought that the English language was being spoken only in the classroom. After completing the assembly, the teacher was previously informed about my observation schedule that I was observing her class for the data collection of my research. We together entered the classroom, they greeted us, saying, “GOOD MORNING TWACHERS” we responded together. When the class moved further, I found the passive students listeners. They did not take part in the conversations with teachers. They only listen to the teachers talk. When the teachers explained in English, they stayed passive but by the time the teacher translated in Nepali the students’ voices came out. The teacher also asked most of the time Yes/No questions only in English, and the students always answered with one word, ‘Yes.’

Likewise, I visited the second school as per my schedule to collect data. It was the fourth period. It was about half past twelve. The teacher was teaching math in class 8. The topic was set. The problems in the book were given in English, and the teacher read it as it was written in the book. While the teacher used the English language the class was almost silent. On the other hand, when the teacher started to describe the problems in the Nepali language, the class became noisy. I meant to say that the students began to take part in the discussion.

The present condition of the students and the teachers in community schools regarding the English language is not commanding. I found teachers’s using mother tongue in the classroom because of two reasons; one the students did not understand the content in English completely and the next the teachers were less competent in English.

Conclusion

This study was conducted by collecting data in public schools of Vyas municipality of Tanahun district. The collected data shows that the public schools also have adopted the EMI policy. Some of the reasons for adopting EMI are to attract students, and to provide quality education. Public schools are forced to implement this policy without any prerequisites as we know, there is only one English subject in a secondary school but all subjects except Nepali are forced to teach using English language no matter how competent teacher is in English language. All the teachers may not have studied English as major subject, in that condition even teacher may lose confidences to speak in English in the fear of committing mistake or error. In this situation, who will teach health and population, social studies, and other subjects through the English as medium of instruction? It has been an issue in public schools now ad days.

The concerned authority does not seem sensible for the effective practice of EMI. The schools do not have basic resource materials. As we all know that all four skills of language must be developed then only learners could use and understand the language better. To develop all the skills, they need exposure. Without materials and exposure, learners cannot acquire these skills. It is difficult for the teachers also to make the content clear unless the students understand the language. The policy and the implementation do not match. So, the learning outcomes of the students are not satisfactory in public schools though the English is used as medium of instruction. So, as we live in multilingual country, we need to respect all the languages. Together with the English language, international language we need to promote and preserve our languages as well. All the students should enjoy their schooling, for that we need to use either English or Nepali language in balance taking consideration of students’ level, their knowledge and necessity of the courses and the context of learning for better outcome.

References

Bista, K. (2011). Teaching English as a foreign/second language in Nepal: past and present. English for specific purposes world. Issue 32 vol.11, 2011. Retrieved from https://e-journal.usd.ac.id/index.php/LLT/article/view/2571

Education Act 2028, 9th amendment

Irahim. J. (2001). The Implementation of EMI (English Medium Instruction) in

Indonesian Universities: Its Opportunities, its Threats, its Problems, and its Possible Solutions*. Presented at the 49th International TEFLIN Conference in Bali , November 6-8, 2001. Retrieved from https://media.neliti.com/media/ publications/143443-EN-the-implementation-of-emi-english-medium.pdf.

Khatri. K. K. (2019). Teachers’ Attitudes Towards English as Medium of Instruction. Journal of NELTA Gandaki (JoNG), II, 43-54. ISSN 2676-1041 (Print). Retrieved from https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/jong/article/view/26602.

Macaro, E., Akincioglu ,M.& Dearden ,J.(2016). English Medium Instruction in Universities: A Collaborative Experiment in Turkey. Studies in English Language Teaching ISSN 2372-9740 (Print) ISSN 2329-311X (Online) Vol. 4, No. 1, 2016. Retrieved from Studies in English Language Teaching (scholink.org).

Poudel, P. (2021). Using English as a medium of instruction: challenges and opportunities of multilingual classrooms in Nepal. Prithvi journal of research and innovation. Retrieved from http://ejournals.pncampus.edu.np/ ejournals/pjri/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/4_PJRI-01121-engedu-43-56-1.pdf.

Shah, B. B. (2019). English as a means of instruction: necessity or obligation in community school of Nepal. Retrieved from https://www.collegenp.com /article/english-as-a-medium-of-instruction;-necessity-or-obligation-in-the-community-schools-of-nepal.

Tang, K.N. (n.d.). Challenges and Importance of Teaching English as a Medium of Instruction in Thailand International College (pp 99-118). English as an International Language, Vol. 15, Issue2.

Tran. T.H.T. & et.al. (2021). Perceived Impact of EMI on Students’ Language

Proficiency in Vietnamese Tertiary EFL Contexts. IAFOR Journal of Education: LanguageLearning in Education. Retrieved from https:// files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1303125.pdf .

Uchihara, T. & Harada, T. (2018). Roles of Vocabulary Knowledge for Success in

English- Medium Instruction: Self-Perceptions and Academic Outcomes of Japanese Undergraduates. TESOL Quarterly. Retrieved from https:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/tesq.453

About Author: Laxmi Shrestha is an M.Ed. from Aadikavi Bhanbhakta Campus, TU. She is an English teacher in a public school in Tanahun. Her interest in research includes EMI, Second Language Acquisition, Sociolinguistics, and Language Teaching.

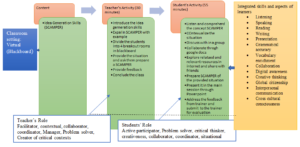

The outbreak of COVID-19 has affected every aspect of human life, including education. The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education system in human history. Social distancing and restrictive movement policies has significantly disturbed traditional educational practices. It has changed education for learners of all ages. Nepal has also suffered a lot due to the lack of adequate and appropriate sustainable infrastructure for the online system. In addition to this, the limited internet facilities in remote and rural areas were the other challenges for virtual academic activities. Many schools remained closed for a long time during the lockdown and some managed alternative ways of teaching. However, the teaching learning activities could not be made effective as expected. The impacts of the pandemic has directly affected the students, teachers and parents.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has affected every aspect of human life, including education. The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education system in human history. Social distancing and restrictive movement policies has significantly disturbed traditional educational practices. It has changed education for learners of all ages. Nepal has also suffered a lot due to the lack of adequate and appropriate sustainable infrastructure for the online system. In addition to this, the limited internet facilities in remote and rural areas were the other challenges for virtual academic activities. Many schools remained closed for a long time during the lockdown and some managed alternative ways of teaching. However, the teaching learning activities could not be made effective as expected. The impacts of the pandemic has directly affected the students, teachers and parents. Prologue

Prologue