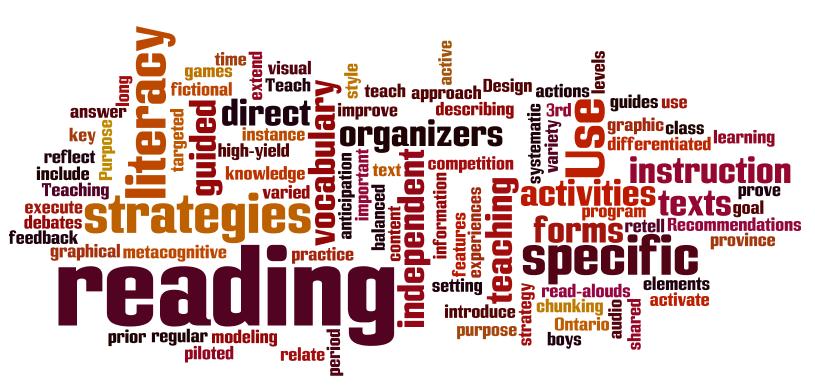

During my university degree and job in Nepal, I needed to read long texts, reports, and books, but I was a slow reader and would be distracted too easily while reading. Or let’s put this way, my reading strategy made it slow. Now, I’m a graduate student in a US university and reading demand is even deadlier, so I use different reading strategies to overcome the distraction and slow reading. In this blog post, I’ll share my reading strategies then and now highlighting some ineffective and effective strategies, which can be useful for students, researchers, and professionals.

How was my reading like?

We used to have five courses a year in campus and each course came with a couple of books or chapters to read.

“Guys, check the course books and the references list. These are the readings for this course.” Our teacher would say referring to course syllabus.

The course book would be one or two, but the reference list would be longer consisting of four/five other books or chapters to read.

One of us would ask, “Do we need to read all these for our exams?”

The teacher would say, “Well, yes and I would say you to read these for your life.”

I wouldn’t care what he meant by ‘read for your life’ but I was concerned the exams were based on those reading because we had/have paper-pencil-based annual exams and a majority of it would depend on our memory and writing speed. If each course would assign at least four readings, that would sum up twenty readings, which was worrisome. Oh my gosh! How could a person like me with a full-time job manage time for them?

My problem was I wouldn’t turn the next page until I know the meaning of every single word and make sense of every single sentence. I used to consult the bulky Oxford English dictionary and write the meaning of new/difficult words either in Nepali or in English all over the pages and sometimes I would note on a separate notebook to keep books clean. The funny thing was occasionally the meanings in the dictionary would be complicated than the words, which would further push me to check their meanings too! Can you imagine? Moreover, I would also go back and re-read sentences to make more sense, but this multiple ‘regression’ (Ahuja &Ahuja, 2008) not only impeded my reading speed but also impaired my comprehension because I used to engage in microstructures of text rather than inferring meaning and making sense from it in a big picture. Despite all this hard work, I would still be unable to make complete sense of the texts, which would result in ‘reading fatigue’. Then, I would be tired of reading and wouldn’t have any interest and motivation to read further. Isn’t that frustrating?

To make the matter worse, I often used to read aloud as I was told somewhere that it would make my pronunciation better (for speaking). Perhaps, read aloud benefitted my pronunciation somehow but it would result in slower reading and affect my comprehension terribly because I remember, while reading aloud, I consciously used to assess my pronunciation and lose the contextual cues and infer meaning from the text. The vocalization (even sub-vocalization) is subject to contribute to slower reading, reading fatigue and decreased comprehension (Ahuja & Ahuja, 2008).I wonder now, what was the purpose of my reading? Why was I distracted from the major purpose (which I believe is critical reading and meaning construction)?

Besides, I used to easily get distracted while reading. Does that happen to you? Like, you read a couple of sentences or paragraphs, then your mind is out on streets, playgrounds, café, parks, theatre, or it would dwell on some memories, though your eyes were still on the texts. These days, distracts are even deadlier with your mobile phones, tabs, or computers! It doesn’t only hold back our reading but also backfire our comprehension because when we pause reading, allow other thoughts to rule our mind, and resume it, we tend to forget the previous section. Sometimes, we don’t get the full picture without reading the entire section of the chapter or the entire text.

These were some of the reasons for me to get scared of long reading list in campus and similar was the problem with reading texts and reports in my job. Now, when I reflect on my reading journey, I find that it’s not how hard you read but how strategically you read that pays off. However, when we run behind making sense of every single word, it’s going to make things harder. It’s only a myth that one needs to understand every single word to construct meaning from a text. The knowledge of 90% words is enough for readers to comprehend texts(Hirsch, 2003), while mastery of ‘5000- 8000’ most frequently used words including key technical terms are good enough to construct meaning from texts as the rest can be guessed and ignored(Martinez & Murphy, 2012).Sticking on every single word would result in missing contextual clues, disconnect meaning between sentences, lose ability to infer the texts. Likewise, it’s also essential to retain the memory of the previous section/sentences and predict what’s coming up in the text. Reading also has a lot to do with smooth eye-mind coordination (Ahuja & Ahuja, 2008) and thought processing to maximize comprehension and critical reflection. Unfortunately, nobody ever taught me reading strategies and meaning construction processes from the text but only suggested the reading lists.

So, how do I read now?

When I joined the graduate program in a US university last Fall, I still had the same reading hangover and suffered a week or two. Professors would assign three to four research papers/chapters every week including weekly writing assignments. As I had two courses to study and one to teach, I was again trapped in reading (and writing). I would be doomed with slow reading and distractions as I had seven to eight readings worth 20 to 30 pages each. So, I started exploring the reading strategies of my classmates and also sought some advice from the professors, which relieved me to some extent. Based on these interactions, I changed my reading strategies and feel comfortable reading texts, papers, and chapters every day now.

First, I figure out the purpose of the assigned readings and the purpose of the authors. My class readings are basically aligned with the themes of the week and professors want us to have a general idea of the texts and dwell on a couple of major issues raised in it. So, I use skimming and scanning strategies. I skim through the title, abstract, key words, headings and sub-headings, infographs/tables/illustrations and reach the end. It gives me a very general idea of what’s the text is all about like having a big picture of forest before figuring out its trees. Ahuja and Ahuja (2008) compare skimming with overviewing the forest and scanning with spotting the trees.

After skimming, I only read those sections which are useful based on my task and purposes, then skip the rest. While reading these sections, I read the thesis statement or argument of each paragraph (and not read the entire paragraph) because that’s the crux of it and identifying the thesis sentence/argument in paragraphs also gives me idea of composing effective paragraphs. So, understanding writing helps reading and vice-versa, because the reading text is eventually a piece of writing.

I also make sure to highlight (underline, color or circle) striking ideas, arguments and major issues in the paper and write quick notes (very short) usually stating my feelings and evaluation over the ideas. I pay more attention in the conclusion section and would read every sentence because that’s where the author/s summarize the ideas of the papers, state the limitations, and show the scope for further studies. In doing so, I go through the notes or highlighted sections once again to summarize my understanding. Then I would pause and reflection on the ideas/issues raised and agree/disagree or advance my perspectives.

What about vocabulary? I still check a couple of words if there are new terminology on titles, abstract and key words section but I have stopped worrying about every new word that I came across. I know there are still multiple new/difficult words but believe me they don’t bother me much to construct meaning of the texts.

Another most useful strategy I use to avoid distraction and speed up reading is the timed reading. Yes, once I’m ready for reading, I turn off notifications on mobile or computer, disconnect Wi-Fi (on mobile) and set the time for the text, which has paid me off with great results in terms of both reading speed and meaning construction. When I set my target to achieve a definite amount of reading in a limited time, I train my mind and orient it towards my goals, which has been amazingly useful for me.

The reading strategies I discussed above are basically applicable for technical texts for university students, researchers or professional and I’m mindful these reading strategies can vary depending on types of texts (ex. literary texts) and purpose of your reading. So, I shared my personal reading struggles and lately practiced reading strategies, which may not necessarily reflect yours. As the purpose of this blog to generate discourse on reading strategies people use, I would appreciate if you could share your reading strategies in the comments below.

The author: Jeevan Karki is a graduate student and writing instructor at the University of Washington, Seattle Campus.

References

Ahuja, P. & Ahuja G.C. (2008). How to increase your reading speed. Sterling Paperbacks.

Hirsch, E. D. (2003). Reading comprehension requires knowledge—Of words and the world. American Educator, 10–29.

Martinez, R., & Murphy, V. A. (2012). Effect of frequency and idiomaticity on second Language reading comprehension. TESOL Quarterly, 45(2), 267–290.

In my perspective one of the most important factors contributing for ineffective in-service teacher training is the attitude of teachers. Most teachers (not all because few are active and work hard) do not feel such training as an opportunity for their professional development, whereas they feel it as a chance to earn extra money. It is a tragedy that we are yet unable to make them feel the importance of it. Therefore, teachers need to change their attitude and apply the skills learnt in training in their classroom. I think a possible solution for this problem can be a good head teacher. If a head teacher has positive attitude towards training and encourages his teachers to apply new ideas in classroom, teachers cannot afford to be reluctant to transfer the skills in the classrooms.

In my perspective one of the most important factors contributing for ineffective in-service teacher training is the attitude of teachers. Most teachers (not all because few are active and work hard) do not feel such training as an opportunity for their professional development, whereas they feel it as a chance to earn extra money. It is a tragedy that we are yet unable to make them feel the importance of it. Therefore, teachers need to change their attitude and apply the skills learnt in training in their classroom. I think a possible solution for this problem can be a good head teacher. If a head teacher has positive attitude towards training and encourages his teachers to apply new ideas in classroom, teachers cannot afford to be reluctant to transfer the skills in the classrooms. A few classroom visits in Nepal can tell us how ineffective the impact of the government-run in-service training has been. When I ask my graduate students why such a wastage of resources, they say the training does not directly link to the real classrooms, ignores local contexts, and does not address trainees’ mental constructs, their needs and expectations. I fully agree with them. However, for me the main culprits for the ineffective teacher training are the trainers. You may ask why. No trainer has been trained to be a teacher trainer. Each of them has a degree on pedagogy not on andragogy. They do not have a faintest idea of adult learning. Because the trainers in the government system have a permanent position, they do not bother for their own development. And they pass on their attitude to the teachers who they train.

A few classroom visits in Nepal can tell us how ineffective the impact of the government-run in-service training has been. When I ask my graduate students why such a wastage of resources, they say the training does not directly link to the real classrooms, ignores local contexts, and does not address trainees’ mental constructs, their needs and expectations. I fully agree with them. However, for me the main culprits for the ineffective teacher training are the trainers. You may ask why. No trainer has been trained to be a teacher trainer. Each of them has a degree on pedagogy not on andragogy. They do not have a faintest idea of adult learning. Because the trainers in the government system have a permanent position, they do not bother for their own development. And they pass on their attitude to the teachers who they train. The in-service teachers should count themselves fortunate for getting the opportunity to learn and to teach at the same time. Also, they should be gratitude to the concerned authority for providing them with such opportunity. However, it is a sad fact that take away from the training session is less and its translation into the actual classroom teaching is even lesser. There could be multitude of causes behind this ranging from training policy to classroom pedagogy. Since the limited space prevents me from digging depth into the issue, I point out two areas of training drawing on my own experience of teacher and teacher educator both. The first is attitudes. It is not uncommon to hear in the training the participant teachers saying, “It only works here in the training hall, not in our schools”. Most participants have this ‘it doesn’t work’ attitude. First, the training should aim at inculcating positive attitudes in teachers. Only the positive beginning can lead us to the positive ending. Here I am reminded of Thomas Friedman’s famous saying, “If it is not happening, it is because you are not doing it”.

The in-service teachers should count themselves fortunate for getting the opportunity to learn and to teach at the same time. Also, they should be gratitude to the concerned authority for providing them with such opportunity. However, it is a sad fact that take away from the training session is less and its translation into the actual classroom teaching is even lesser. There could be multitude of causes behind this ranging from training policy to classroom pedagogy. Since the limited space prevents me from digging depth into the issue, I point out two areas of training drawing on my own experience of teacher and teacher educator both. The first is attitudes. It is not uncommon to hear in the training the participant teachers saying, “It only works here in the training hall, not in our schools”. Most participants have this ‘it doesn’t work’ attitude. First, the training should aim at inculcating positive attitudes in teachers. Only the positive beginning can lead us to the positive ending. Here I am reminded of Thomas Friedman’s famous saying, “If it is not happening, it is because you are not doing it”.  NCED conducts many in-service teacher trainings out of them TPD is the nationwide training program. These trainings actually implemented by Educational Training Centres (ETC), LRCs and RCs under the guideline developed by NCED. Except TPD, other several training programs like CAS training, MLE training, MGML training, training for the teachers using English as MoI etc.

NCED conducts many in-service teacher trainings out of them TPD is the nationwide training program. These trainings actually implemented by Educational Training Centres (ETC), LRCs and RCs under the guideline developed by NCED. Except TPD, other several training programs like CAS training, MLE training, MGML training, training for the teachers using English as MoI etc. As a resource person, I see there are a couple of reasons why in-service teacher training is not helping to improve the pedagogy in classroom. First of all, the student-teacher ratio in some school is very high. In few schools there are up to 120 students in a single class! Therefore, it is quite challenging to make classroom interactive. When a teacher tries to do something new in group/peers classroom goes out of control and hence they return to old method. Besides, teachers also have to teach more than usual number of periods because of lack of teachers. Therefore, they are not encouraged to try something new because of more work load.

As a resource person, I see there are a couple of reasons why in-service teacher training is not helping to improve the pedagogy in classroom. First of all, the student-teacher ratio in some school is very high. In few schools there are up to 120 students in a single class! Therefore, it is quite challenging to make classroom interactive. When a teacher tries to do something new in group/peers classroom goes out of control and hence they return to old method. Besides, teachers also have to teach more than usual number of periods because of lack of teachers. Therefore, they are not encouraged to try something new because of more work load. First of all, I am quite convinced that in-service teacher-training programs can never be ineffective because they definitely provide some visions and frames for teaching. A trained teacher approaches to the students with some sort of framework, philosophy and guidelines; he or she could deal with students even on the way or on a bus far better than untrained ones.

First of all, I am quite convinced that in-service teacher-training programs can never be ineffective because they definitely provide some visions and frames for teaching. A trained teacher approaches to the students with some sort of framework, philosophy and guidelines; he or she could deal with students even on the way or on a bus far better than untrained ones. The government has envisioned the provision in-service teacher training for the community school teachers for the efficiency and efficacy of teaching methodology exploited while conducting classroom lessons. The considerable amount of national budget allocated in the education sector has been separated for this purpose. Every year such trainings are conducted in RCs, LRCs and educational training centers on need based. It should have resulted in the tremendous improvement in the educational sector of the nation by now but the reality is something beyond our imagination. That is to say, the in-service teacher training does not have tangible impact on the teacher’s educational pedagogy. There can be several factors behind it. Some of the factors that bring about this gap might subsume:

The government has envisioned the provision in-service teacher training for the community school teachers for the efficiency and efficacy of teaching methodology exploited while conducting classroom lessons. The considerable amount of national budget allocated in the education sector has been separated for this purpose. Every year such trainings are conducted in RCs, LRCs and educational training centers on need based. It should have resulted in the tremendous improvement in the educational sector of the nation by now but the reality is something beyond our imagination. That is to say, the in-service teacher training does not have tangible impact on the teacher’s educational pedagogy. There can be several factors behind it. Some of the factors that bring about this gap might subsume: Every year, the government invests a good amount of budget to provide in-service and refresher training to in-service teacher aiming to increase educational quality of the nation. In spite of having such efforts, there is still not much visible improvement in the pedagogy in the classroom. Some prominent causes behind the present situation can be as follows:

Every year, the government invests a good amount of budget to provide in-service and refresher training to in-service teacher aiming to increase educational quality of the nation. In spite of having such efforts, there is still not much visible improvement in the pedagogy in the classroom. Some prominent causes behind the present situation can be as follows: