Abstract

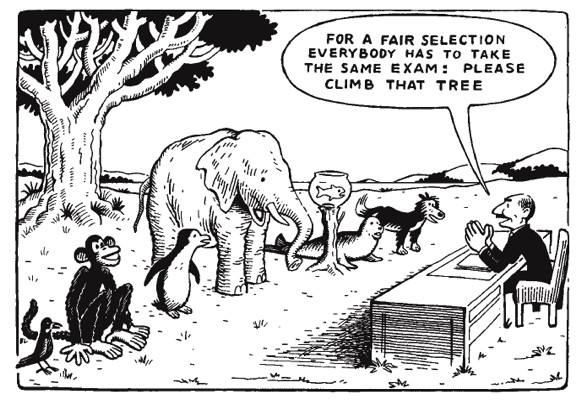

The use of English as a medium of instruction (EMI) in schools has become a growing issue in the context of Nepal. This paper explores some examination practices in the EMI policy adopted community school (EMI school) in Nepal. Considering an EMI school as a case, I have collected qualitative data using multiple methods such as observation, interview, and informal interaction concerning the issue, and analyzed and interpreted the data thematically. The students need explanations of every question in the Nepali language before they write the answers. The negative washback seems to be extended to the examination hall. The examination practices employed in the EMI school raise a serious question about the way they learn the content using EMI.

Keywords: Examination, EMI policy, memorization, dependence, negative washback.

Introduction

Due to globalization, the use of EMI at school and university levels has become a contemporary and emerging issue in the global context and so is the case in the context of Nepal. Several studies from home and abroad show that the stakeholders of schools and colleges are shifting the medium of instruction (MOI) used in the schools and colleges to English, especially in the countries where the native languages being used are other than English, like Nepal. For this reason, the EMI issue has been a fresh area to study for researchers and academicians.

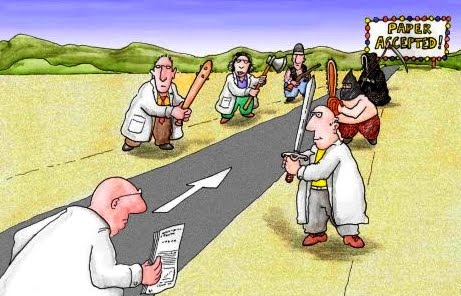

A number of studies (e.g., Baral, 2015; Bhatta, 2020; Brown, 2018; Ghimire, 2019; Gim, 2020; Joshi, 2019; J. Karki, 2018; Khanal, 2020; Khati, 2016; Ojha, 2018; Paudel, 2021; Phyak, 2013, 2018; Poudel, 2019; Ranabhat, Chiluwal, & Thompson, 2018; Sah, 2022; Sharma, 2018; Weinberg, 2013, to name a few) have been conducted concentrating on the EMI/MOI issues in Nepalese context. These studies especially focus on the assumptions, teachers’ identity, ideology, agencies, opportunities, challenges, possibilities, policies, and practices of EMI/MOI issues in general; however, less attention is paid to the examination practices in particular. So, in this paper, I endeavor to explore the examination practices employed by the EMI school selecting a secondary community-based school in a rural area of Bagmati Province, Nepal as a case.

Methods of the Study

This study employs the “case study” (Stake, 2008; Yin, 2016) research design selecting an EMI school as a “case” and the “examination practice” of the school as a phenomenon of the study. Multiple methods (i.e., nonparticipant overt observation of examination activities, interviews with three teachers teaching in Grades four and five, and informal interaction with two students of Grades four and five) were used for information collection. The data were transcribed and translated into English and interpreted categorizing them into themes.

Results and Discussion

The information was interpreted categorizing them into two themes: dependent on the teachers, and the existence of negative washback effect. They are discussed with supporting details below.

Dependent on Teachers

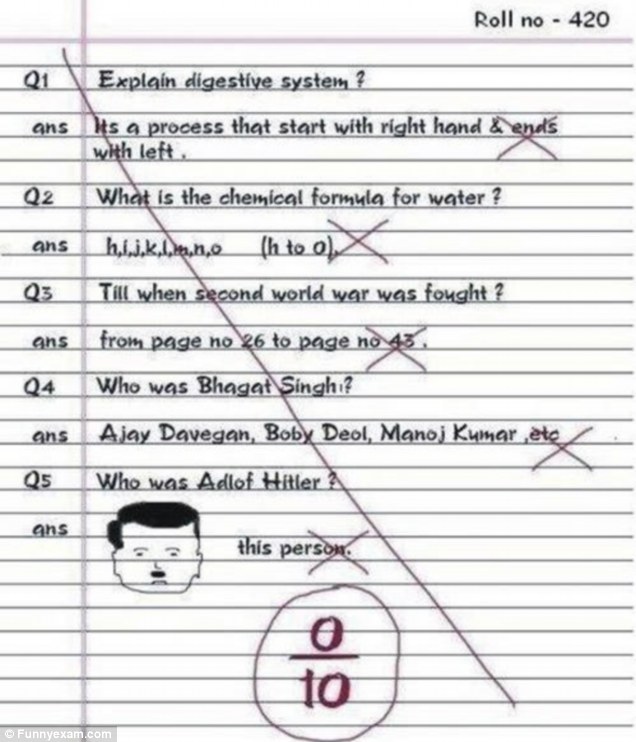

The students participated for the examinations in the hall seemed to be dependent on the teachers for writing the answers. The students started writing the answers to the questions only after the subject teachers’ explanations of the questions with the clues to write the answers. The students seek clarification of the instruction of each question written in English for understanding in Nepali language used in the paper. They wanted the meaning of the particular question, and meaning and spelling of the words, from which the students got the clues for writing the answers to the objective questions particularly. Regarding this, I have mentioned two short pieces of discourse held during the examinations of Class 5, Science and Class 4 Social Studies respectively in the hall.

Examination discourse # 1

S1: Miss, esko question sarnu parchha? (Miss, should we copy the question? [in the answer paper]?)

T: timiharule question sarnu pardaina answer-answer matra lekha (No, write only the answers).

S2: Miss, jo duiko (a) ke bhaneko ho bhanidinuna (Miss, please, tell me what Question 2 (a) means).

T: pani dherai chiso bhayo bhane ice banchha ,thik ki bethik? (Water can be converted into ice on cooling, true of false?)

S2: e… (um. . .)

S3: Miss, question no 3 ko (a) ko meaning bandiununa (Miss, please, tell me the meaning of Question 3 (a)).

T: J-u-p-i-t-r [spelling the letter] jupiter, jupiter bhaneko grahako naam ho thaahaa chhaina? (Jupiter is a planet, don’t you know?)

S4: Miss, aath [8] number ko (a) ko bhandinuna (Miss, please, what is meant by Question 8 (a)).

T: What are amphibians? Amphibians ke lai bhaninchha?

S4: amphibians ko meaning ke hunchha, miss? (what is the maning of amphibians?)

T: jamin ra paani dubai thaaumaa basne janawaar ho ni asti nai class maa padheko hoina? (amphibians live both on land and water, don’t you know?)

Examination discourse # 2

S1: Sir, “maaghi”ko meaning ke ho? (Sir, what is the meaning of “maaghi”?)

T1: “maaghi” bhaneko parbako naam ho (“maaghi” is a name of a festival)

S2: Maam, “gaura” bhaneko ke ho? (Maam, what is the meaning of “gaura”?)

T2: “gaura”bhaneko euta chaad ho (“gaura” is a festival).

S3: Miss, “mother” ko spelling bhandinununa (Miss, please, tell me the spelling of “mother”)

T2: lu hera tyeti pani najaaneko? “m-o-t-h-e-r” hoina? (Oh! You don’t even know the spelling of m-o-t-h-e-r mother?)

S4: Miss, yo (C) number ko ke bhaneko? (Miss, please, tell me what question C means?)

T2: “alcohol ko prayogale ke asar garchha” bhaneko ho? (It means-what are the effects of consuming alcohol?)

Note: The expressions written in italic are the Nepali words used by the participants and in the square brackets are my explanation.

During an interview, concerning the use of Nepali language, a teacher, Tarun expressed that they often used it “due to the low level of students’ knowledge in English”. He added “you saw in the examination hall, they could not write anything unless we [teachers] explained each question in Nepali”. The interesting point is that no single English sentence was used in the conversation though the EMI policy is adopted in the school.

There can be many reasons for behind the use of Nepali language in the discourse. One reason can be the teachers’ low proficiency in English which is similar to some studies in the past (e.g., British Council, 2013; LaPrairie, 2014; Mohamed, 2013; Sah & Li, 2020) and they feel difficulty in teaching and making the students comprehend in English. The other can be the students cannot understand due to their low level of English language knowledge (Wirawan, 2020). Whatever the reason may be, the students fully depend on the teachers for the use of Nepali language to understand the questions and solve the problems. The shreds of evidence in the discourses held in the examination hall and with the teacher imply that there is enough space for suspicion of accomplishing the learning outcomes set in the curriculum with the use of EMI.

Extended Negative Washback

The “negative washback” refers to the undesirable effect of the test on teaching and learning activities (Alderson & Wall, 1993; Chan, 2018; Cheng & Curtis, 2004) that precedes and prepares for the assessment. The negative washback seems to have been extended to and reflected in the examination practices in the EMI school. That is to say, the teaching-learning activities were performed keeping the testing system in mind, and during the examination, the problems to be solved in the examination hall were frequently signaled referring back to the classrooms activities as a clue to the examinees to solve the problems.

Once in the examination hall, Lila, a teacher, responded to a question made by an examinee “Didn’t I ask you to read the same answer some days ago in the class while practicing for the exam?” She added, “Do it in the same way” in a reminding tone. This expression signaled the extension of negative washback effect to the examination. Moreover, in the examination hall, it was seen that the answer to one of the subjective questions of many students was written exactly the same way in terms of its content, length, and structure.

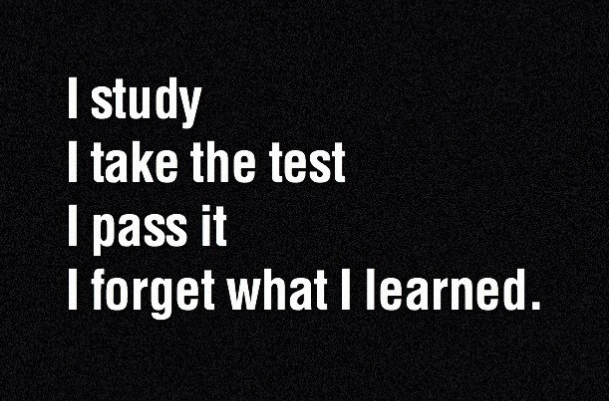

With reference to this issue, one student expressed, “our teachers provided the questions and their answers just before the examination started” and she added that the students “memorized the answers for writing in the examinations” while I informally interacted with her. In line with the same view, another student, showing the evidence in his book, put his remark that “the teachers ticked the questions to be asked in the exam when the examination schedule was published” he further stated that they read the same answers to prepare for the exams. They both agreed that they normally get help from the teachers to solve the questions in the examination hall.

Teachers even agreed with the statements shared by the students. In an interview, a teacher, Jina, remarked that she normally selects “some possible questions with their answers to be asked in the examinations” and asks the students to memorize the answers. Relating to the issue, a Social Studies teacher, Lila stated, “I pick out some questions from the important chapters and repeat them many times for the examinations”. She further added “the students feel difficult to write the answers unless we provide them with the answer clues.” Her statements reflect the extension of negative washback to the examination practices. The pieces of evidence mentioned reveal that replicating the questions, which were practiced and asked the students to memorize earlier in the classes for the examination purposes, and helping the students to solve the questions in the examination, in other term, extension of negative washback effect, appeared to be a common strategy prepared and applied by the teachers in the EMI adopted school.

The extension of negative washback effect to the examination practices in the EMI school may not be favorable for learning because they may well miss the mark to reflect the “learning principles or the course objectives to which they are supposedly related” (Cheng & Curtis, 2004, p. 9), they oppose to “learning through exploration or discovery” (Tania & Phyak, 2022, p. 141), and they do not match the examination policy (T. M. Karki, 2020) prepared by the concerned authorities. Supporting the issue, Manocha (2022) views that it may not be a good strategy because it does not allow the students to use their “prior knowledge of language” and discourages them to share their “stories and experiences related to the text”, as a result people may question in the effective implementation of EMI policy from the teaching and learning perspectives.

Conclusion

In this study, I have explored the examination practices employed by the EMI-adopted community-based school. The students seem to be reliant on the subject teachers and their Nepali explanations of instruction mentioned in English and each problem appeared in the English-medium question paper. The extension of the negative washback effect to the examination hall was observed in the study. Although this study is limited to a single but discontinuously upgraded EMI policy-adopted school located in a rural area of Nepal selected for the case study, it provides information that can be true to the other EMI school more or less in a similar context. For more wide-ranging, trustworthy, and extensively applicable outcomes, similar but larger-sized studies in the future are recommended.

References

Alderson, J. C., & Wall, D. (1993). Does washback exist? Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 115-129. doi: 10.1093/applin/14.2.115

Baral, L. (2015). Expansion and growth of English as a language of instruction in Nepal’s school education: Towards pre-conflict reproduction or post-conflict transformation (Master’s thesis). The Arctic University of Norway. Tromsø, Norway.

Bhatta, C. (2020). Assumptions and practices of English as a medium of instruction in community schools of Nepal (Master’s thesis). Tribhuvan University, Department of English Education, Kirtipur. Retrieved from https://elibrary.tucl.edu.np/handle/123456789/9864

British Council. (2013). Can English medium education work in Pakistan? Lessons from Punjab. Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.pk/sites/default/files/can_english_medium_education_work_in_pakistan_-_british_council_2013.pdf

Brown, R. (2018). English and its role in education: Subject or medium of instruction? In D. Hayes (Ed.), English language teaching in Nepal: Research, reflection and practice (pp. 13-34). Kathmandu: British Council.

Chan, K. L. R. (2018). Washback in English pronunciation in Hong Kong: Hong Kong English or British English. Motivation, identity and autonomy in foreign language education, 27-40.

Cheng, L., & Curtis, A. (2004). Washback or backwash: A review of the impact of testing on teaching and learning. In L. Cheng, Y. Watanabe, & A. Curtis (Eds.), Washback in language testing: Research contexts and methods (pp. 3-18). Mahwah: Taylor & Francis.

Ghimire, N. B. (2019). Teachers’ indentity in English medium community school in Nepal: A narrative inquiry (A mini research report). Tribhuvan University, Office of the Dean Faculty of Education, Kirtipur, Kathmandu.

Gim, S. J. (2020). Nepali teacher identity and English medium education: The impact of the shift to English as the medium of instruction at Nepali public schools on teacher identity (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database. (UMI No. 28257970)

Joshi, B. R. (2019). Use of English as a medium of instruction in Nepalease context (Mini research). Office of the Dean, Faculty of education, Tribhuvan University. Kathmandu.

Karki, J. (2018). Is English medium instruction working? A case study of Nepalese community schools in Mt. Everest region. In D. Hayes (Ed.), English language teaching in Nepal: Research, reflection and practice (pp. 201-218). Kathmandu: British Council.

Karki, T. M. (2020). A Study of practical examinations: Provision and practices. Tribhuvan University Journal, 35(1), 97-110. doi: 10.3126/tuj.v35i1.35874

Khanal, G. P. (2020). English-medium schooling in the context of Nepal: A critical review. Siddhartha Journal of Academics, 2, 22-31.

Khati, A. R. (2016). English as a medium of instruction: My experience from a Nepali hinterland. Journal of NELTA, 21(1-2), 23-30.

LaPrairie, M. (2014). A case study of English-medium education in Bhutan (Doctor in education). Institute of Education, University of London. Retrieved from https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10021621

Manocha, S. (2022). Participation of Saora children in MLE and MLE plus schools in Odisha, India: Lessons learned and lessons to learn. In L. Adinolfi, U. Bhattacharya, & P. Phyak (Eds.), Multilingual education in South Asia: At the intersection of policy and practice (pp. 149-171). London: Routledge.

Mohamed, N. (2013). The challenge of medium of instruction: A view from Maldivian schools. Current Issues in Language Planning, 14(1), 185-203. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2013.789557

Ojha, L. P. (2018). Shifting the medium of instruction to English in community schools: Policies, practices and challenges in Nepal. In D. Hayes (Ed.), English language teaching in Nepal: Research, reflection and practice (pp. 187-200). Kathmandu: British Council.

Paudel, P. (2021). Using English as a medium of instruction: Challenges and opportunities of multilingual classrooms in Nepal. Prithvi Journal of Research and Innovation, 43-56. doi: 10.3126/pjri.v3i1.37434

Phyak, P. (2013). Language ideologies and local languages as the medium-of-instruction policy: A critical ethnography of a multilingual school in Nepal. Current Issues in Language Planning, 14(1), 127-143.

Phyak, P. (2018). Translanguaging as a pedagogical resource in English language teaching: A response to unplanned language education policies in Nepal. In K. Kuchah & F. Shamim (Eds.), International perspectives on teaching English in difficult circumstances: Contexts, challenges and possibilities (pp. 49-70). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Poudel, P. P. (2019). The medium of instruction policy in Nepal: Towards critical engagement on the ideological and pedagogical debate. Journal of Language and Education, 5(3), 102-110. doi: 10.17323/jle.2019.8995

Ranabhat, M. B., Chiluwal, S. B., & Thompson, R. (2018). The spread of English as a medium of instruction in Nepal’s community schools. In D. Hayes (Ed.), English Language Teaching in Nepal: Research, reflection and practice (pp. 81-106). Kathmandu: British Council.

Sah, P. K. (2022). English as a medium of instruction, social stratification and symbolic violence in Nepali schools: Untold stories of Madhesi children. In L. Adinolfi, U. Bhattacharya, & P. Phyak (Eds.), Multilingual education in South Asia: At the intersection of policy and practice (pp. 50-68). doi:10.4324/9781003158660-4

Sah, P. K., & Li, G. (2020). Translanguaging or unequal languaging? Unfolding the plurilingual discourse of English medium instruction policy in Nepal’s public schools. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(6), 1-20. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2020.1849011

Sharma, S. (2018). Translanguaging in hiding: English-only instruction and literacy education in Nepal. In X. You (Ed.), Transnational writing education: Theory, history, and practice (pp. 79-94). Thousand Oaks: CRC Press Book.

Stake, R. E. (2008). Qualitative case studies. In Strategies of qualitative inquiry (3rd ed., pp. 119-149). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Tania, R., & Phyak, P. (2022). Medium of instruction, outcome-based education, and language education policy in Bangladesh. In L. Adinolfi, U. Bhattacharya, & P. Phyak (Eds.), Multilingual education in South Asia: At the intersection of policy and practice (pp. 132-148). London: Routledge.

Weinberg, M. (2013). Revisiting history in language policy: The case of medium of instruction in Nepal. Working Papers in Educational Linguistics, 28(1), 61-80. Retrieved from www.gse.upenn.edu/wpel

Wirawan, F. (2020). A Study on the teaching media used by the English teacher at SMP Muhammadiyah 2 Malang. Jurnal Ilmiah Profesi Pendidikan, 5(2), 89-95. doi: 10.29303/jipp.v5i2.115

Yin, R. K. (2016). Qualitative research from start to finish (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

About Author

Tek Mani Karki is a Lecturer at Tribhuvan University, Department of English Education, Mahendra Ratna Campus, Tahachal, Kathmandu. Currently, he is pursuing his Ph.D. degree entitled “English as a Medium of Instruction in Community Schools of Nepal: Policies and Practices”. His areas of interest in research are language education policy and teacher professional development.

[To cite this: Karki. T. M., (2022, October 15). Examination Practices in English as a Medium of Instruction School [blog post]. Retrieved from https://eltchoutari.com/2022/10/examination-practices-in-english-as-a-medium-of-instruction-school/]