Abstract

In the changing paradigm of pedagogies, learners’ involvement and engagement has been considered primarily. Learners are the key components and their different aspects of knowledge and skills need to be incorporated in teaching learning activities. With reference to the aforementioned remarks this paper aims to explore learner centered integrative approaches to bridge the gap of learnability. This study is conducted in Chandigarh University, as a research scholar, I got opportunity to deal with MBA students with Professional Development Skill course and reflected in-self and collected students experiences towards the courses. Classroom teaching learning strategies and situations are the main interventions in which learner centered diverse skills were integrated and studied. The study revealed learners’ motivation, self-preparedness, enhanced communication and problem-solving skills followed by language skills. Moreover, learners were found engaged and encouraged to participate into activities as a result they could bridge the gap of learnability of language, content and context.

Keywords: Collaboration, Learner centered, Learner centered integrative approaches, soft-skills, self-preparedness

Introduction

Learners are the agents of growth and development, similarly, they intend positive changes in them followed by the surroundings. In our traditional mindset we control the learning situations and it is judged in terms of achievements made through some basic formal tests. My mind is looking for the answer of a genuine question raised by one of the graduate students after examinations. She asked me, till when we will be experimented with the dilemma of frameworks of formal tests? Will there be any provision of addressing our needs, thoughts and existing inner capacity? Can you suggest me any places where there is the respect of the practice-based knowledge? I think these are the representative questions of the learners of 21st century, once I read the lines in (Carrillo & Flores, 2020) I found the motives of learners engagement in self-pace situations. Similarly, (Bovermann & Bastiaens, 2020; Johnson, 2006; Wong & Jhaveri, 2015) in different situations and time indicated learning as a psychological and sociological preparedness to the learners where the teachers are facilitating the situations with changing paradigms and new dimensions. Furthermore, the world is shrinking in the course of knowledge economy and practices. The learners are believed the first source of peeping down the world and the teachers, parents, surrounding are the supporting agents. The present context demands learners’ visible involvement in learning process with due respect of their thoughts and skills they equipped with. Therefore, this reflection paper aims to explore the learner centered integrative approach through the intervention of practical activities in professional development course.

Methods

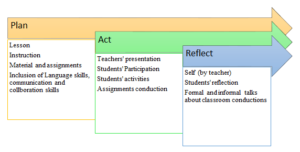

The method of the study was based on the intervention implemented as per discussed in the course file. I got interested to observe the learners’ activities and activeness in this practical course. As per the nature of the course, plan and guideline I taught students. I observed students’ engagement in developing soft skills and other skills such as language skills and communication skills. I prepared journal for reflection of the daily activities. Similarly, interaction with students made me able to reveal the students’ experience towards the course and intervention. The intervention is presented below here in the diagram.

Diagram 1: Intervention model

Intervention for learner centered integrative approaches

During the Covid-19 crisis, the teaching-learning process in the classroom with physical presence was not totally possible in all regions of the world. Many Educational institutions from basic level to higher education have devised a strategy for incorporating new technologies and alternative teaching methods to engage students in the learning process. According to statistics presented by UNICEF (2020), more than one billion pupils are stuck in classrooms throughout the world owing to lockdowns and school closures in more than 188 nations. In the UNICEF (2020) COVID-19 survey, more than 73 percent of 127 nations said they use internet platforms and more than 75 percent said they use television to deliver remote learning for education. Many of these countries are experimenting with alternative methods of providing continuous education to pupils through the use of various technologies such as the internet, television, and radio. However, inadequate internet connectivity, lack of teachers’ and students’ digital knowledge and skills provide a barrier to online education. Concerning to the issues during pandemic, there could be varied alternative ways that we could own and develop as per the need of curriculum, context and social framework. On the other hand, Murtikusuma et al. (2019) discussed that teachers’ and students’ attitudes, actions, activities, and cultural and economic values are all linked to technological adaption. Computer technology, online learning communities, and ICT tools have all been identified as new paradigms in education that promote classroom connections through a virtual setting, allowing students to acquire collaborative and interactive skills. Although, there were several possibilities through Online Learning Community (OLC), learning process needs to be contextual and learner centered integrative approaches need to be incorporated to the new paradigms in the 21st century.

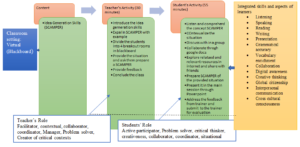

Lerner centered integrative approaches (LCIP) enabled learners to participate in virtual learning context as an alternative modes of teaching learning. For example, as a research scholar I observed students’ participation in classroom activities and motivation towards learning and sharing through blackboard in Chandigarh University in India. It’s a new experience to me and taking this as an example of paradigm shift. Align with the ideas of (Lamont et al., 2018; Lantada & Nunez, 2021; Leite et al., 2022; Leshem et al., 2021) learners’ readiness, institutional plan and teachers’ responsible thoughts following by the behaviors could introduce alternative learning possibilities. It is obvious that the learners are the change agents and teachers need to facilitate the situation in the realm of practicality and relevancy. Here I am presenting one sample activity conducted in 90 minutes session describing how learners participate into activities and integrate the language skills and technology within the class framework in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Learner centered integrative approaches (LCIP) implementation model

Diagram 2 depicts the overall situation of intervention and implementation to introduce learner centered integrative approaches in professional development skill courses. Particularly, the session focused to the language development, interpersonal skills, soft skills and learnability. As mentioned in the diagram the role of the teacher is faciliatory and the manager and students are the conductors of all events take place in the classroom. Teachers support and encourage learners to participate. The main responsibility of the teacher is to clarify the concept of the topic and instructions for the activities. The rubric-based evaluation and clear instructions create interactive situations. Another beauty is the situation of Question and answering. Both the teachers and students ask and respond to the questions mutually. Similarly, learners’ motivation and enthusiasm to involve in the activity is effective as they are evaluated based on their performance in the classroom. Therefore, I claim that the process given in the diagram resemble to the Learner centered Integrative approaches (LCIP) and make learners responsible to their learning.

Reflection and conclusion

With reference to the intervention, I discussed with the students regarding their experience and perception to the practical courses, nature and potential challenges informally. This study’s students used blackboard as a virtual mode of learning and Learning Management System (LMS), which helped them develop communication and teamwork skills with their classmates. Many participants viewed classroom interaction through integration of language, content and context as a useful, suitable, accessible, and student-friendly. During the intervention time, I examined students’ activities and found that they were engaged and motivated to solve problems through interaction, teamwork. They were actively involved in completing assignments and submitting them by the due date. My observation revealed that a teacher’s instruction, orientation, and regular engagement can be useful in involving students in a learning situation.

I found that the learners are encouraged with the practical courses and the course is helping them in placement in multinational or the reputed companies such as Google, Microsoft, Amazon and many others. Similarly, they explained the collaborative efforts they developed. For example,

S1: I am very much delighted with the Professional Development skill course. Initially, I doubt myself as thinking introvert student because I need to participate in every activity. With the encouragement of the teacher, I could participate in discussion in any forums.

S2: By the help of the professional development skill course, I am able to tackle with the challenges as I improved language, interpersonal skills and soft skills. Similarly, I experienced the real learning situation.

S3: Obviously, I am encouraged with the course and teaching learning activities. I personally feel I am learning something for me and hopeful of getting good placement in good companies. if I rate myself, I improved my language and interpersonal skills with the help of the course.

S4: The content, language and context integrated activities enabled us to engage and collaborate with friends remotely. Our participation remained task-based as per the teacher’s instructions and course materials posted in the blackboard. The most significant aspect of learning was that we gained communication and collaboration abilities.

As per my observation the practical course is linked to the life changing goals because students experience seems motivating towards the integrating of several skills and aspects of language learning. Students collaborated, coordinated, and communicated ideas among the groups independently and now they are habitual to present and share ideas integrating listening, speaking, reading, writing skills in every section. They found improvement in language and social interaction perspectives.

Following the ideas of (Kerres, 2020; Scott & Palincsar, 2013; Vygotsky, 1978) socio-cultural perspectives and technological integration could lead to increase learner’s independency as a result learners can interact with several elements such as society, language, content and emotions any critical situations like COVID and any others. Learners’ participation, motivation and interaction regarding to the situation enable them to intervene newness in learning as a result learner centered integrative approaches (LCIP) could be existed and they prepare themselves to face the challenges to rectify new motives of learning for personal and professional development.

References

Bovermann, K., & Bastiaens, T. J. (2020). Towards a motivational design? Connecting gamification user types and online learning activities. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-019-0121-4

Carrillo, C., & Flores, M. A. (2020, Aug). COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 466-487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184

Johnson, K. E. (2006). The sociocultural turn and its challenges for second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 235-257.

Kerres, M. (2020). Against all odds: Education in Germany coping with Covid-19. Postdigital Science and Education, 1-5.

Lamont, A. E., Markle, R. S., Wright, A., Abraczinskas, M., Siddall, J., Wandersman, A., Imm, P., & Cook, B. (2018). Innovative methods in evaluation: An application of latent class analysis to assess how teachers adopt educational innovations. American Journal of Evaluation, 39 (3), 364-382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214017709736

Lantada, A. D., & Nunez, J. M. (2021). Strategies for continuously improving the professional development and practice of engineering educators. International Journal of Engineering Education, 37(1), 287-297.

Leite, L. O., Go, W., & Havu-Nuutinen, S. (2022). Exploring the learning process of experienced teachers focused on building positive interactions with pupils. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(1), 28-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1833237

Leshem, S., Carmel, R., Badash, M., & Topaz, B. (2021). Learning transformation perceptions of preservice second career teachers [Article]. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2021v46n5.5

Murtikusuma, R., Fatahillah, A., Hussen, S., Prasetyo, R., & Alfarisi, M. (2019). Development of blended learning based on Google Classroom with using culture theme in mathematics learning. Journal of Physics: Conference Series,

Scott, S., & Palincsar, A. (2013). Sociocultural theory. Education. com.

UNICEF. (2020). Resources on education and COVID-19. UNICEF. https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/covid-19/

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the Development of Children, 23(3), 34-41.

Wong, L. T., & Jhaveri, A. (2015). English language education in a global world: Practices, issues and challenges. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Researcher’s Bio: Yadu Prasad Gyawali is the Assistant Professor under the Faculty of Education at Mid-West University (MU), Surkhet Nepal. Mr. Gyawali is also a teacher trainer, consultant, and editor for different journals. Moreover, Mr. Gyawali is a Ph.D. scholar at Chandigarh University, India. His areas of interest include teachers’ professional development and ICT in second language education.

Dear teachers, educators and learners,

Dear teachers, educators and learners,