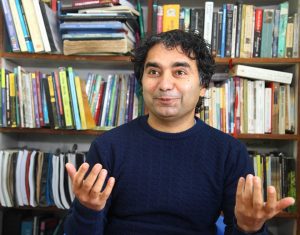

Interviewer: Bal Ram Adhikari

Professor of English, Govinda Raj Bhattarai’s career straddles English language teaching and literary writing. He has contributed to the field of Nepalese ELT as an ELT practitioner, material producer, and teacher educator. A former NELTA president, Bhattarai is also synonymous with postmodernism in Nepali literature. His writing has ushered in the mode of Nepali creative writing, especially Nepalese criticism, essays and fiction, what we call the post-modern era in Nepali literature. He is appreciated and also criticized for the use of subjective perspective in criticism, fusion of facts into fiction in essays, and intertexuality in fiction writing. Here we are trying to explore the dynamic space between postmodern thoughts and ELT practice in Nepal– the areas Prof. Bhattarai has been long associated with.

1 Seven years ago you co-authored an article entitled English language teachers at the crossroads highlighting the possibilities and challenges Nepalese ELT practitioners had ahead. Could you elaborate on your use of English teachers being at the crossroads from the postmodern perspective of the paradigm shift in theory and practice that we have been experiencing in all academic fields?

Bal Ram, as I am representing my nation, that is, a unique existence made up of a particular history and geography and politics, I am aware of this time and space that is giving voice to my observation into the quantification of a very vague, say abstract, phenomenon. This phenomenon is philosophy, because your question is ultimately related to philosophy. Therefore, I must ask your permission to allow me to use some extra bites (of space) for my words so that I can make ‘our’ position clear. Extra space because your question demands such an answer as reads like an intertext or transtext that is like a text made up of various texts, and yet no text is written there. This may demand some elaboration naturally.

In pragmatics or discourse analysis, even socio-political beliefs like one’s religion, education, social relations, or any activity one partakes every day are taken as a text. Every moment one lives contributes to a larger text. That text draws its meaning from innumerable disciplines and natural facts. In fact the world since time immemorial has been governed by one philosophy or the other — of politics, art, literature, culture, science, religion. In totality, say of LIFE.

Philosophy is like a package program that we require to live this life as a person or a society. Every such philosophy is supplied by a particular TIME and SPACE. Every linguistic, cultural or religious group, a race or nation or any territory cultivates its own philosophy over a period of time that governs the life-cycle of the people. That package has everything for the followers’ education, their literary principles, marriage systems or death rites, interpretation of dream, role of a mother or use of painting for that matter. Sets of philosophy keep changing from time to time. Sometimes if the ‘consumer’ communities or nations grow weaker, they are forced to ‘buy’ some new sets like modern (or foreign) goods from alien lands. And gradually, people are forced to relinquish their native or indigenous philosophy and adopt or gradually nativize the alien one (s). A community cannot survive without a philosophy or a set of belief system. Something should occupy its mind all the time.

The Oriental world and our ancestors had their own set of philosophy. It was quite rich, almost incomparable to any in the world, but the outside world (especially the West) encouraged us to humiliate our own mother, and we were forced to adopt a new mother. It was colonization of not only land, but also of our mind and thought, and attitude towards life. This kept destroying us and different parts of the world for more than three hundred years. We were destined to be free, ultimately, but were left dented and semi-paralyzed with a master slave ‘dichotomy’ and a psychosis of ‘we can’t do, we do not deserve, we are inferior’, and worst of all, ‘we don’t have’. Their so called enlightenment rescue project had half destroyed us. Frantz Fanon, in his The Wretched of the Earth (1963 trans.) has rightly said: Colonization is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures, and destroys it.

Yes, we were perverted in this, as our native philosophy was disfigured gradually by them. And we didn’t know. Our geography was not colonized but our minds were. Even today, we have no regrets, and feel content to witness an avalanche of irreparable loss eroding us every moment, because we are brainwashed to accept all defeats with a smile. This was the first wave of all driving us away from our own ‘civilization’. This is teaching us every moment to be like them and not us. How ridiculous!

Now I would like to touch upon the second wave in passing that tried to obliterate what was left after the first calamity. The second wave was the philosophy based on sheer materialism that was represented by Marxism. Slogans for equality and material development brought the second wave of whirlwind easily. At that moment man lost his faculty of reasoning temporarily; as a result that swept away much that was left of what human beings possessed as precious values.

The second wave also believed in colonizing crowds of mass within their own ideological cages, and kept them warring militantly against great nothingness, devastating people in an unprecedented scale. They obliterated a permanent world (of native and indigenous philosophies) with a utopian haven of false assurances. We have seen millions of brothers and sisters being divided into classes, and prepared for unending clashes; gone for this and left in ruins and ravages. This philosophy proved a successful destroyer of native brands of philosophical packages. These are the greatest enslaving campaigns human beings underwent until the dawn of the 21st century. These two together clouded some centuries of human history. Both these waves were great homogenizing forces.

Have we ever stopped and thought of these forces? These factors deeply disturbed the human mind, especially in our part of the world. It may take centuries to heal the scar and to repair the moral, or say spiritual, degradation.

We were the great architects of our own education, in fact we had crafted a draft for world education, but since the lock to its entrance was broken with the western key, we have become oblivious of the treasure rooms. Since then we became great followers of the western world.

As we are bereft of everything, we feel so; we possess this sort of inferiority because we do not look at our own faces, so we are following them. Our gullibility sells at a high price, so we are used to mimicking everything. Greek philosopher Epictetus had proclaimed: Only the educated can be free, but today we can see in our contexts the reverse seems to be the reality. I can hardly see any trace of our education system based on our values or philosophy of education.

Let me relate this to your concern of a paradigm shift. Modernism was a kind of hegemony that had its roots in the west, and was nurtured by materialism because modern science fed it, though not as sheer as that in Marxism. In fact the west governed the world of thought, and so of philosophy and art, for about a hundred years, ending in the Second World War in the west. All our activities from writing to teaching were molded accordingly. Colonization transported them very easily. However, history shows that modernism freed the world from the ignorance and brutality of the dictatorial past, but then people wanted more options, newness and greater degrees of freedom. In apt words, they wanted to keep progress of the world going like new inventions that can never be stopped.

It was during 1970s that this desire for progress led man to postmodern convictions. Postmodernism encouraged man to stand boldly for his freedom, and to possess an ever questioning mind to find the truth for him. Let him explore his own personal truths, let him protect his local truths and let him stand for his national truths as well and defend his beliefs. It is therefore that new disciplines like ethnic studies, women’s studies, cultural studies, diasporic studies etc are emerging today. Truth is the ultimate means to happiness and one can gain a new truth by doubting his present condition, his status, or all accepted beliefs and facts. Stuart Sim (2012) regards postmodernism as a rejection of many, if not most, of the cultural certainties on which life in the West has been structured over the past couple of centuries. He regards the Enlightenment as a western project to oppress humankind, and to force it into certain set ways of thought and action not always in its best interests. Postmodernists are invariably critical of universalizing theories as well as being anti-authoritarian in their outlook. To move from the modern to the Postmodern is to embrace skepticism about what our culture stands for and strives for.

At the same time I feel postmodernism is both a liberating as well as, and no less than, a homogenizing force. Contradictorily, it promotes ‘individual’ existence but is yoked to technology in such a way that the latter has been the tool for the promotion of the former. Therefore, postmodern features we experience are characterized by a ubiquitous phenomenon; moreover instead of being a liberating agent, it is in fact an all-homogenizing force. A sheer hegemony, and another kind of all encompassing techno-driven colony. Postmodern premises defeated one grand narrative of dictatorship and colonialism, and at the same time this cultivated a newer variety (of colonialism) with the help of technology known as postmodern condition in Lyotard’s words. A bigger grand narrative can be seen. Despite this, the only hope this promises us is local freedoms in different scales, though we cannot breathe without technology and we cannot revive the local power we lost. Let’s move ahead with boons and curses both on our heavy shoulders. This is our present predicament and sits on our shoulder like a boulder on Sisyphus’ head.

For me postmodernism is nothing more than a search for freedom, freedom from all sorts of bondage, and a deep search for alternatives to the existing values and principles. It is a quest for remaking, resetting, rethinking, revisiting, reinventing– everything that matches the pace of time. It also indicates a faster pace of human progress (or decline) in a completely techno driven world.

Postmodern is a philosophy of options and alternatives, it calls for a break with the structure bound, center seeking modernism. This has had a deep influence all over the world and global forces spread it very fast. We can see traces of this in Indian literature and critical works produced as early as 1970s. Nepal was attracted much later.

I introduced the term Deconstruction as vinirmaan into Nepali for the first time in 1991. (Please refer to Kavyik Aandolanko Parichaya; Introduction to Poetic Movements published by Royal Nepal Academy). In a span of twenty years now, we have traversed a long route and are near the centre of Nepalese philosophy of postmodernism, which stands first of all for freedom from the fear of dictatorship, because this philosophy empowers the modern man to be free. This may mean differently for the rest of the world.

Against this historical and theoretical backdrop, let me come back to your concern of ELT. Yes, this idea dawned upon me when I became aware of enormous changes being introduced in critical theories of Indian academia. I was also aware of the western publications where the new paradigm had permeated all the fields of academic and scholarly activities. New paradigm had been a buzz word, and they indicated postmodernism as a great change agent. Subsequently I had begun to see new horizons in the Nepalese contexts as well. Gangaram-ji was also aware of this so we drafted that idea and published an article titled English language teachers at the crossroads in 2005 issue of the Journal of NELTA. However, our ideas were crudely shaped. We were a bit skeptical.

The following year, I had an opportunity to attend the 40th TESOL conference held in Tampa, Florida. It was 2006, I had participated for the first time in such a huge (truly international) conference of ELT professionals. I had never imagined that the President of NELTA would be a non-entity among some 8,000 participants (all leading figures, each leading a world of innovative ideas with the support of technology and paradigm shift). The participants represented different corners of the world. In fact I was at a loss to see such an immense teaching ‘industry’ that had grown so vast and so fast without ‘our’ notice. It struck me not because the number was large, but because I saw Nepal’s ELT could be plotted nowhere till then. It was disseminating all traditional values based on structuralism.

By writing that article, I wanted ‘my’ language teachers to be aware of the changing world scenario, to be aware of a great paradigm shift experienced in the field of our profession, that is, language teaching. I use the word ‘my’ as a President of NELTA because my duty was to address all the ELT professionals in the country, to tell them what changes are taking place in the philosophy of teaching and learning, so that they can cope up with the changing situation. In fact, each and every action of life is geared according to some philosophy.

Yes, my intention was to remind them of the ‘postmodern’ turn, or to tell them how things (beliefs and philosophies) have changed in the world and how these have changed our world, that is, language teaching. We spoke out clearly — philosophy of thought and perspectives have changed, teaching methods and learning techniques have changed, teaching materials have changed, we are facing a world governed by drastic changes. If we are not aware of this, our traditional, rule-governed ‘structural’ methods will surely fail us and leave us in a blind alley.

I could tell them the breaking paradigm shifts proudly because I felt almost ‘desperate’ to see a different world of ELT professionals– the language teachers, materials producers, publishers and technology at TESOL conference in Tampa .

A fast developing electronic culture is introducing miracles every day. Words have now got wings, and voices can fly and visually the world is omnipresent– I saw great magical works being performed there.

I had used the word postmodern in Nepali, referring to its critical zones. But I was wary of using this in teaching industry, so we in passing mentioned the word ‘postmodern’ categorically. Now it has become a buzzword in our academic world, this has been introduced in the syllabus and textbooks as well in research– though this has led to much frustration and confrontations. The use of postmodern may still sound an avant-garde’s effort before a dogmatic noun? However, no other word can capture the aggressive time that was (and is) molding our life at an unprecedented scale.

It has been more than two decades now that I have been using the term specifically to characterize some of our literary efforts in Nepal. But gradually, I began to feel that there is no field of knowledge or life untouched by a kind of newness. People have begun to feel the expansion of global force and its encroachment into their private world. The giant is all encompassing, and so modern life becomes impossible to survive without succumbing to it. Is it our defeat if the global world flattens us into one? There is no answer in this flat earth, in the words of Thomas Friedman in his The World is Flat (2002).

2. Postmodern thought is taken as the continuous process of suspecting, revisiting and redefining our beliefs in the nature of truth and of knowing, and the nature of reality. What can be the implication of this epistemological and ontological process of thought for teaching in general and English language teaching in particular?

You are right. In answer to question 1 above, I have made it clear that postmodernism claimed a great shift in total philosophical standpoint. Like any other philosophies that provided a departure from existing practices, this also brought all encompassing effects. There is no field of knowledge or skill, the foundation of which is unaffected by this paradigm shift.

In the beginning I concentrated on the principles of writing and criticism, mostly in Nepali literature. A whole decade of my writing was confined to the introduction to and practice of postmodern criticism. Gradually my duty expanded and my attention drew towards its total effects. I presented for the first time a paper entitled Postmodernism in Education in 2008. It was in Sukuna Multiple Campus of Morang. Never before had I faced such a vehement criticism in my academic career. Some fundamentalist teachers attacked me severely and the dogmatic critics who were backed by dogmatic political beliefs were against my proposal. My points were: doubt your beliefs and works, stop and question your practices, may be you were wrong so far, may be you can discover new unexplored areas which can open up new vistas in teaching. Philosophies keep changing and so do teaching principles. You put a question: Is my method of teaching appropriate? Are we following appropriate curriculum, or do we need to stop and rethink over it? All our socio-political values and norms have changed; they are changing so fast, so should not our system of education follow such changes endlessly?

There is no fixed set of values and truths or our perspectives. In my childhood days the philosophy of education was guided by a maxim (in Sanskrit). It read:

laalayet bahabo doshaa taadayet bahabo gunaa

tasmaat putram cha shisyam cha laalayennatu taadayet

I learned this by rote (it was in our textbook) in grade VIII, so whenever the teacher punished us physically, I thought this is the way how teaching was prescribed in the shastras. This verse literally means: there are many defects in caressing or loving, and many benefits of beating, therefore, every son as well as a disciple (student) should be beaten.

This philosophy remained our norm for more than three thousand years. At the dawn of the twenty first century, we are shocked to find that this moral principle excludes girl children from education, and moreover this advocates beating the boys severely. But we have realized that this principle was totally wrong, and so female education is given higher propriety. Moreover, teachers and parents are warned against child abuse, which includes beating or corporal punishment or any kind of harassment– mental or physical. Now our educators are changed and the persons to be educated are changed, so the contents of education, methods and materials of teaching are changing in such a way that we cannot believe what the world is doing today.

We can hear the slogans for girl education, women education, inclusive education, education for the deprived like blind and deaf or prisoners and criminals. We are correcting our mistakes of yesterday all the time, at every step of life. Our philosophies are temporary, always at a state of flux, keep changing continually. This is only an instance.

I kept convincing people of the paradigm shift, and gradually I got more support from them, especially from Prof B N Koirala of the M Phil program supported my cause. With his support, I delivered some lectures there, likewise some guest lectures were arranged annually at KU too. In the meanwhile, an article appeared in Shikshya Journal of Secondary Education board. My campaign invited me to a country wide tour; I visited from Ilam to Surkhet, Jhapa to Mahendranagar. Postmodernism visited with me in the form of literary principles and writing, of thinking and teaching, and many more. I presented papers, delivered speeches; attended discussion sessions, and the new generation now became quite aware of the nature of the new truth. I wrote not less than 500 pages in a matter of a decade. Consequently, everybody started to realize that the time has changed, our values and beliefs have changed, and the very foundation of existing philosophy is shedding its old leaves.

This foundation of philosophy is called epistemology. I need not define this concept any further. But then, since we teachers are supposed to earn our living by trading in or dealing with principles of education or teaching we need to know the very meaning of epistemology. It is no more than what we are doing, which education we are imparting, what kind of truth it contains, which truth we consider final, what its foundation is, and the question of whether the foundation is strong or shaking, or has already been demolished in other parts of the world. This is not specific to teachers only, what happens if a farmer does not know about the new breed of animals or seeds and manures and continues with old practice? He will spoil everything and ruin himself. So we traders of truth should also be aware of the new brands of education on sale in the world market.

As a result of untiring efforts of years, our academicians saw the worth of this element and they allocated some teaching hours to the M Ed Education course. Likewise, postmodernism has crept into almost all Masters’ level courses. In a matter of a decade we can see a different picture today. Education stands for a whole cycle of processes– from the production of learning materials to their delivery mechanism and the evaluation of outcomes. In each stage we are (and must be) just provisional, tentative, keep our decisions at a state of flux so that we remain open to anything new. This is how knowledge and education widens and broadens.

Postmodern perspectives will help our teachers realize that nothing is final, not even the best principle in practices. No truth is final, no belief and practice. We must keep on looking for new possibilities. And technology has expedited this in an unprecedented scale. It is like applying Derrida’s principle of gaps and absences. If you doubt you can find a new truth hidden, unexplored in the gap. Truth comes from absences. And a final thing is never achieved, we are chasing a mirage because our physiological world also keeps changing, the pace of techno-culture has brought changes at a tremendous speed in our belief system, value system. It is here that we also apply another postmodern term differance that Derrida coined, which stands for the perpetual difference in meaning, and the nature of truth and reality. You try to grasp and it evades. This very principle applies to education too.

The second point is ontology, a branch of philosophy that discusses how truth is tasted, or what is it that exists? This also leads to the question of ‘existence’ or ‘being’ and its classification. This forms the content of knowledge. This allows us insights into the nature of objects and existence and ways of measuring the same. We need to know this because we need to define air, water, mass, solid, feeling, anger, and sleep, or anything that we are supposed to teach.

Our experiences related to ontology are not final either. Therefore, knowledge system is not decisive, and we need to believe in the fast changing nature of everything including philosophy. And this applies to education. The pace of change was quite slow in the past, now it has become tremendously fast.

The whole of education system is manifested physically in curriculum, textbook, evaluation cycles, yet its soul is the content, what we teach. We need to leave our whole education system open ended, and in a state of flux. ‘Open ended’ will be a better word so that you can add or delete or modify the particles of truth with the change in our belief. As a result, some outdated beliefs will be deconstructed and replaced with new ones, the way a cycle of gradual decay and regeneration is unendingly active in nature. So, education system as a whole should be like belief system in eastern epistemology of revolving in chakra, that is, the cycle.

In the absence of doubting mind and skepticism, education will be devoid of creativity, innovation and regeneration. ELT is not an exception. Every thing comes under these philosophical premises. Actual students, their teachers and those who confine themselves to the functional or performance level may not perceive its underlying level. This calls for the critical and reflective eyes to see the undercurrent.

When we come to a deeper level of philosophy, we come face to face with a problem that forces us to think about what we are doing, and to question whose philosophy is guiding us. Not only ELT, the whole of education system is based on western epistemology, or ontology for that matter, ours is completely different and fully ignored. I regret this state (of our epistemology and ontology) being ignored. The whole of our education world is misfounded on ‘their’ system or pattern.

Whatever may that be, the performance level cannot notice this. A core, national body of educationists should oversee and take diversions and decisions, which is not easy either. We don’t have a separate philosophy for language teachers. But then, I made it clear before, the postmodern turn has a deep influence over our total system of thought and function. Now the world should accept the existence of margins. Which means there is no ‘only one’ English, there are multiple varieties, each seeking their identity and recognition. Secondly, we no longer stick to a prescriptive viewpoint and accept or reject a piece of text accordingly.

Nepal is also producing its own variety which may be colored by its sound, vocabulary system, and sentence structure. Every native variety is sure to be colored by it language and color. So we must be liberal towards this to some extent, this will be ratified by the principle of multiple centers, or decentering of a grand narrative– that we cannot produce perfect English. We are spending more than 30 percent of our budget allocated to English education. What is the use of this if we fail to reap the harvest of our investment? Innumerable factors are sure to make our variety a different one. So we speak English the way we do, read it the way we do, and write the way we can. This does not mean that we will be happy with its creolization or pidginization. My point is, let us not worry too much, let us not feel humiliated and debase ourselves. We do learn it for functional values, which stands for communication needs of different types. Writing represents the core of Nepali variety. We should not hesitate to welcome creative writings in different genres. We have produced a quite substantial number of books in both literary and technical English. Creative writing should be regarded as a variety of Nepalese literature. Ours has been excluded so far. And we cannot wait until we produce the English of British or American or even Australian variety. Among world varieties, Nepali will be one, though each of sub-centers will have one epicenter that will regulate our English to a large extent, not to a full extent, however. I have explained to you why we think so. We have planted this tree, and it has started bearing fruit which will help us grow globally.

I welcome firstly all translators of Nepal to come boldly ahead and play a more vibrant role in the enhancement of knowledge industry; I suggest them to use untranslatable native terms and concepts instead of losing our sense or choosing a circumlocutory path. Let the world know we do a namaste and not good morning.

I welcome secondly all writers from the Nepali Diasporas to use untranslatable Nepali terms as they are in their English texts. Don’t try to make your texts read as if they were written by a perfect British or American writer. This applies to all creative writers using English as a medium and writing about Nepal, wherever they are.

Like this:

Like Loading...