A few months ago, while attending a talk on campus (at Stony Brook University) one afternoon, given by Elana Sohamy, an Israeli scholar, I had a moment of despair.

The title of her talk was “multilingual testing” and the backdrop of her presentation was the monolingual regime of language testing and its effects on multilingual language users across the world.

As teachers of language and writing/communication, we keep saying in theory that language learners take 3-5 or even 9-11 years to be fluent and accurate in a new language, depending on where and how they learn. But in practice, we continue to resort, very quickly and thoughtlessly, to the logic of pragmatism, of institutional policy, of the need to make sure that our multilingual students can perform in English.

Here’s the problem with our dead habits and thoughtless embracing of the current monolingual testing regime: Usually, monolingual tests don’t predict overall academic performance by multilingual students, simply because the tests confuse language proficiency as a predictor of a lot more than just language proficiency that academic transition and success involve. It would be nice if, for instance, a TOEFL score of x predicted whether a graduate student is able to listen, read, speak, and write well enough to be a successful graduate student in, say, a graduate program in ecology. But it doesn’t.

Two students with the same TOEFL score (even with similar academic records from the same education system) regularly perform significantly differently, and often, students with much lower TOEFL scores perform better than with much higher scores. Why? Because academic performance is a matter of process involving a lot of factors–grit, support, psychology, personality, content knowledge, and a lot more.

While TOEFL is not as bad as GRE, I must add, the company selling this product back-peddled a few years ago when it ignored that adding the spoken test (as it is administered by using an underdeveloped technology of speech and accent recognition) makes the test even less valid. TOEFL’s test of writing skills is as much of a joke as SAT writing test is: it rewards certain semantic, syntactic, and rhetorical tricks that do not constitute good writing in college/university. And while its listening and reading passages are based on quite authentic classroom situations, the validity of the overall score is significantly hampered by the outdated view of language proficiency that the test is based on. Those who make these tests are still unable to understand how multilingual English speakers around the world perform sociolinguistically in academic and other contexts.

I heard today that ETS is starting to respond to the basic idea that multilingual English speakers should be assessed in terms of how they draw on more than one language to achieve communicative goals. But the company’s primary goal of efficiency for itself trumps the principles of validity and effectiveness. And this is to say nothing about the blatant lie about universality of the content on which the tests are based, the egregious amount of money the test fee translates from US dollars to some of the local currencies, the intellectual insult for students with learning disabilities, and many more issues.

Sohamy showed that immigrant students scoring in the 60th percentile when tested in L2 only were able to score in the upper 80s when the questions were provided in both L1 and L2. This means that when educators allow learners to start academically succeeding while still having some “issues” with their language, they learn English much more effectively in the process. This is a no brainer: when I start a semester, I tell my nonnative English speaking students in class that they “shouldn’t worry about [their] language” and instead “focus on doing the research, coming prepared to actively participate in class, drawing on [their] prior knowledge, being excited about learning and sharing ideas.” To teachers, it is really a no brainer: It is possible not to put the cart of language learning in front of the horse of the process of education. It is possible not to follow the backward logic of ETS — of treating language as something that you learn “before” you join the learning party!

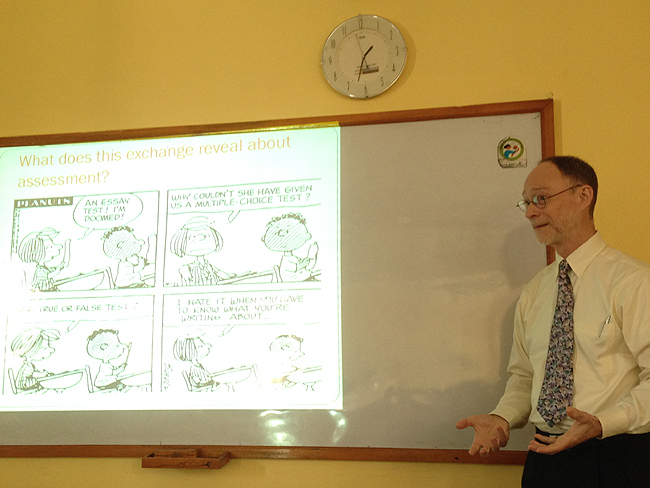

Gatekeeping is necessary but it doesn’t need to be so outdated and invalid. Assessment is necessary but it doesn’t need to be decoupled from learning and teaching.

Now, some readers may object: “I have to make sure that students I admit have a certain level of language proficiency.” Well, there are two significant problems in that “pragmatic” stance. First, someone who scored well on the TOEFL may have been linguistically privileged and proficient, but there is no guarantee that he/she is academically capable or committed. TOEFL doesn’t measure subject knowledge, and, again, it doesn’t measure grit. Second, one could say that admission officers look at academic transcripts in order to review the applicant’s academic caliber. Guess what? Academic transcripts from different countries (and even from different academic systems from the same country) cannot be compared–which is one of the reasons people turn to TOEFL in the first place. Back to square fifteen.

We’re confusing pedagogy with policy, process with desirable proficiency, outcome with entry level proficiency, and our own bias with the need to rely on a system that we admit is flawed but seemingly without good alternatives. What if start by thinking outside of these easy frameworks? What if we start by embracing what Elana Sohamy called “critical language testing”–testing based on skepticism toward established regime that are not in the business of fairness and sophisticated thinking. What if we can adopt parallel regimes, including ad hoc approaches, that we can use in order to challenge ourselves?

What if we can ask all the ten students whom we want to admit to our doctoral program to call us on Skype, Hangout, Viber, or Facebook phone and have a twenty minute conversation each, in order to use our own conscientious judgment, instead of a TOEFL score?

What if?

Shyam Sharma is, PhD in rhetoric and composition from University of Louisville, is assistant professor of writing and rhetoric at State University of New York, Stony Brook.