EMI has been a hot topic for research and interaction locally and globally. Choutari Editor Jeevan Karki has spoken to Prem Phyak, a PhD scholar from the University of Hawaii, US on EMI. Mr. Phyak critically shares his opinions on practices and realities on EMI and suggests some ways forward for EMI practice in Nepal. Here it goes:

Nepalese public/community schools are switching the medium of instruction to English day by day and the government is also in the campaign of training the teachers for promoting EMI. Is EMI the need of time or an effect of linguistic hegemony?

This is a complex question; it requires a thorough observation of local context and an critical analysis of what language education research findings have shown. Let me try to be as specific as possible. First of all, it is not quite clear why English must be the medium of instruction from Grade 1. What’s the purpose of English as the medium of instruction (EMI) policy? Does this policy really help children access both linguistic and academic knowledge? To put it differently, what’s wrong with teaching content area subjects (e.g., Social Studies, Mathematics, and Science) in Nepali and/or any other languages that students understand better? Of course, the English language has an important space in global multilingualism particularly to access globally available socio-economic and educational resources. However, this taken-for-granted assumption does not work quite well in education (teaching-learning process) particularly in the context where children speak languages other than English outside classroom (For many children in Nepal, English is the third language and they do not need to use English in their everyday social interactions). Whether or not students have a better understanding of the content of teaching/curricula largely depends upon whether or not the language used as the medium of instruction in school is comprehensible to them. Studies from all over the world have shown that most low-achieving and drop-out students are taught in a language other than the language(s) they speak at home/community.

The basic principle of learning in the classroom is: if students don’t understand the language of instruction, they are not able to achieve the curricular goals. Most importantly, they are, directly and directly, excluded from the whole learning process; students are not able to invest themselves in performing cognitive skills such as comprehending, evaluating, analyzing, and critical/independent thinking. What we must know is that if we care about and would like to put education and children at the forefront, the imposition of any language as the medium of instruction (e.g., EMI) in which students cannot fully operate in the classroom leads to numerous social, psychological, and cognitive issues. Studies have further shown that if children are forced to learn in “an insufficiently or poorly developed second [/foreign language], the quality and quantity of what they learn from complex curriculum materials and produce in oral and written form may be relatively weak and impoverished” (Baker, 2011, p. 166). It is basically wrong to force students, who have never learned and used English before they come to school, learn all the content area subjects in English (without any English language support) from the first day in school. We should also know that learning in Nepali has already been a problem for many children.

I think the question is not whether “EMI is the need of time”; rather we must engage in analysis of whether EMI is an appropriate approach to ensure access and meaningful participation of all children in teaching-learning process in the classroom. The current de facto EMI policy is fundamentally flawed; it seriously lacks academic/educational justifications that are grounded in language education theories and best practices. It is quite surprising to see that public schools are switching from Nepali medium to EMI policy without examining its educational, social, and cognitive ramifications. I don’t quite understand the intention of the government as well; if we closely look at the Ministry of Education’s policies and plans such as Education for All, Millennium Development Goals, School Sector Reform Plan and National Curriculum Framework, it wants to promote multilingual education by considering children’s home/community languages a resource for an equitable and quality education. Through these policies, the government has shown its commitment to ensure access, equity, and quality education for all children. Thus, it is completely unethical for the Ministry of Education to divest from its commitment to multilingual education and invest just on EMI as a monolingual approach to medium of instruction policy. In this sense, we can say the current EMI policy seems more hegemonic, i.e. it is shaped by the global dominance of the English language but not by its educational/academic rationale in the multilingual context of Nepal. However, I would like to mention that any policy (be it Nepali-only or English-only) that promotes monolingualism in education is hegemonic for multilingual students.

In Nepal, do you think we are ready for switching the medium of instruction especially in public/community schools?

Whether we are ‘ready’ for an EMI policy is not what we must be debating about. Rather we must engage in critically examining whether EMI contributes to promote both access and quality in education. Here, I would like to mention two things: first, we already have English as a ‘compulsory’ subject from Grade 1. From the first day in school, children must learn English, irrespective of their linguistic backgrounds (I learned English from Grade 4, but was never taught in EMI in school). My own observations and other studies show that public schools and teachers are facing a number of challenges to teach English-as-a-compulsory-subject from Grade 1. How can we imagine that the EMI policy works in this existential reality?

Second language acquisition and bilingual education studies have revealed that when students are not fully functional in the languages taught/used in schools, they are not able to fully engage in cognitive activities and perform academic skills well. We must also be aware of the fact that strong academic skills and knowledge/concepts that students develop in one language is always transferable to learning a new language. This means that it is important to help children develop their academic, cognitive, and linguistic abilities in their home language/community language before they are taught any new language. We have already seen this issue in teaching English-as-a-compulsory-subject. Therefore, we should first engage in understanding and reimagining how to teach ‘compulsory English’ effectively. I think we must be happy if we are able to effectively execute the English-as-a-compulsory-subject policy.

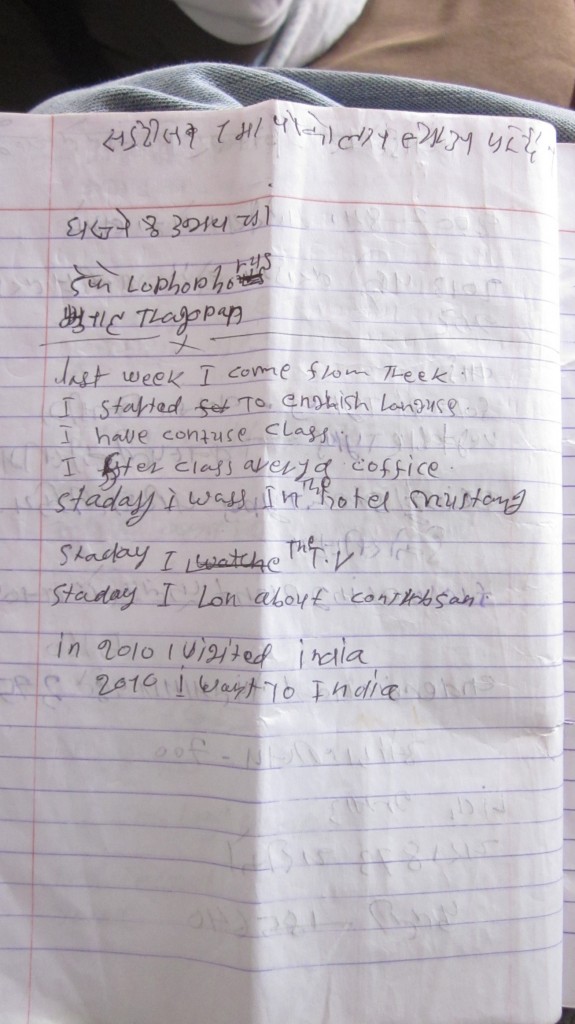

Most importantly, we must not forget that each academic subject, grade, and level has specific objectives that the nation wants students to achieve. In other words, the nation expects students to learn specific content knowledge and skills by the end of a subject, grade and level. While talking with me, teachers (science, social studies, mathematics, and even English) have said that it is ‘impossible’ to achieve subject-, grade-, and level-wise objectives through EMI. Let me share an anecdote. I was observing a Grade 2 science class; the topic of the lesson was the characteristics of living and non-living things. The teacher first asked students to open the science textbook (English translated version of the national textbook in Nepali) and wrote the topic on the board. He kept on reading the lines from the textbook and asked a series of questions to the students. What are living things? What do living things do? All the students were silent. I heard some students asking questions to each other in Nepali to check whether they understood what the teacher was teaching. The most difficult moment was when the teacher was unable to explain the meaning of the word ‘sensitivity’ [one of the characteristics of living things] and could not provide its actual meaning in Nepali to the students. Students remained frozen unless the teacher allowed them to talk in Nepali. As the students could not respond to the questions in English, the teacher himself wrote all the answers on the board and asked them to copy. There was no teacher-student communication at all, but very little student-student interaction in Nepali. The whole lesson was like an English language teaching class, rather than a science lesson. I have observed so many other Science and Social Studies lessons that end up being lessons on the “English language”. After each class observation, I asked Social Studies and Science teachers whether EMI is contributing to achieve the subject-, grade-, and level-wise goals of education. All teachers said “No” and preferred to teach these subjects in Nepali.

My point is that the language that is used as the medium of instruction in schools should not be detrimental to learning. I have seen that EMI is negatively affecting students’ academic skills (use of language for specific genre/communication, independent/collaborative learning, and critical thinking) and knowledge. What is most dangerous is that the de facto EMI policy has projected (quality) English language learning and teaching as synonymous to quality education, which is no other than a myth.

Which is the right level/age to introduce EMI in our education system? Why?

It depends upon whether or not students actually need EMI. The current EMI policy is very much top-down and based on very weak ‘commonsensical ideas’. What I am saying is that a language policy must embrace ‘on-the-ground’ language practices and realities and should be backed up by language education theories and findings; it should not be based on non-academic/education assumptions that a few people think might work well for all the children.

Talking of the right level to introduce EMI, we must be clear about some basic ideas about language and language ability. First, it is important to understand what language abilities are necessary in education. There are two general language abilities: conversational and cognitive academic language proficiency. Conversational proficiency is concerned with interpersonal communicative skills such as holding a conversation, introducing each other, talking with shopkeepers, and organizing meetings. On the other hand, cognitive academic language proficiency includes more complex language abilities needed to handle curriculum contents. It includes language abilities to engage in complex higher order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, evaluation, hypothesizing, and generalizing in specific academic areas such as Social Studies, Mathematics, and Science.

Studies have shown that students take 2-4 years to acquire conversational language abilities while they take 6-8 years to develop cognitive academic language proficiency. This happens in very well planned educational policies with competent teachers, sufficient resources, and a continual support from the government. You know how badly our educational plans and policies are development without any comprehensive research. We must understand that conversational language abilities do not reflect cognitive academic abilities. In other words, we cannot judge students’ cognitive academic ability in terms of their fluency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills in English. We must know whether students can cope with academic content areas through English. Considering the current failure rate in English (even in basic interpersonal skills), unplanned educational scenario, and an extremely limited understanding of language education in a multilingual context, I cannot exactly tell what level we should begin EMI. What I can say however is that introducing EMI without understanding existing conversational and cognitive academic language abilities of both students and teachers is detrimental to both access and quality in learning. A comprehensive plan based on an extensive research study must be developed, piloted, and examined what works and what does not. A non-negotiable principle we must keep in mind is: the language gap should not create educational/learning gap among students.

As Alan Davies, a famous applied linguist who has immensely contributed to the beginning of Nepal’s English language teaching, has recently argued, the expansion of English in Nepal (both as medium and subject) must not be guided by any ‘political motive’ (although it happened when he was leading a 1984 ELT Survey), rather it should be guided by an academic motive. In the 1984 ELT Survey and his 2009 article, Alan Davies has recommended that it is better to start English from Grade 8 so that students are well prepared to learn English and more resources (both teachers and other materialistic resources) can be concentrated on teaching better English. But as the secretary of the Ministry of Education and the representative from the royal palace rejected this academic idea, his survey team had to negotiate and agree on the Grade 4 start. But they have clearly mentioned that lowering English to Grade 1 is not academic sound and desirable. But as we seen now the Ministry of Education has already introduced English-as-a-compulsory-subject from Grade 1 and now promoting it as the medium of instruction.

If we to go for EMI, where should we start from- tertiary level to prepare teachers or from the school level?

I am not sure if I understood this question well. If you want me to comment on teacher preparation for EMI, I have to say two specific points. First, before we talk about teacher preparation we must be clear about the purpose of EMI. Most public schools are forced to introduce this policy because they want to increase the student number so that they get more teacher quotas from the government. They also want to compete with private schools. However, all these arguments are non-academic and very superficial that conceal real issues in public school management. Second, if we would like to discuss the issue of medium of instruction on the academic ground, we should seriously think about how we can prepare teachers to help children, who come from multilingual, multicultural and multiethnic backgrounds without having any exposure of the English language, learn curricular contents better. Based on experiences from all over the world, universities develop language teacher education programs and courses to address issues that teachers face on-the-ground. However, we do not have a strong language teacher education program that prepares competent teachers who can better handle a multilingual class in Nepal.

Let me share two issues with regard to teacher preparation for EMI. First, the way this policy has been pushed without setting up a rigorous teacher education program that both educates and trains teachers on the issues of language education does not seem to be sustainable and realistic. A professional-development (PD) model of teacher training, a famous model of teacher training in Nepal, is not sufficient for the teachers who have to work with a new language education policy. Thus, it is important for the Ministry of Education to collaborate with the universities to develop a new language teacher education program to deal with the current language issues. Second, and most importantly, the new teacher education program must embrace a multilingual approach to language teacher education in which teachers explore various models and approaches to teach multilingual students multilingually. In other words, they should know the fact that a multilingual medium of instruction policy not only promotes learning multiple languages, including English, but also promotes strong academic content knowledge. What I am saying here is that the ways in which teachers have been trained now simply promotes the monolingual ideology of ‘teach-in-English-for-English’.

Children in private boarding schools are taught in English medium and exposed to English language and culture since the first day of their admission. Similarly, all subjects expect Nepali are taught in English and public schools are literally copying the same practice. Do you think it is a good practice or there should be some limitation regarding the use of English language in schools?

Yes, you are right. Public schools are imitating what private schools have been doing in terms of the medium of instruction policy. As we know, private schools focus on English language teaching both as a subject and the medium of instruction. Let me mention two points: a) as private schools are profit-oriented institutes, they have been promoting the English medium of instruction policy as a principal feature of education even when the use of languages other than Nepali were banned in public schools. They taught English from Grade 1 even when the public schools were asked to teach English from Grade 4. Most private schools are located in urban cities and affordable only for high-middle class people; and b) private schools are considered ‘better schools’ because of their students’ higher pass percentage in School Leaving Certificate Exams (SLC), a gateway to higher education. Every year, private schools excel public schools in students’ passing rate in SLC. One of the major reasons for private schools’ success is the greater awareness of parents who send their kids to private schools. As these parents are already conscious about and can invest their time, money, and other resources in their kids’ education, most private school students receive proper guidance and resources (from both school and parents) that help them succeed in SLC. Contrary to this, most public school students, who live a rural agrarian life in lower-class families, do not have all these luxuries. And there are other political, educational, and managerial issues in public schools. Thus, many public school students are unsuccessful in SLC. This gap rooted in socio-economic class differences has eventually constructed a commonsensical assumption that private schools are better and their EMI policy is the only way to obtain quality education.

Public schools are following what private schools have been doing in terms of EMI policy. In various interactions (both formal and informal) with me, head teachers and District Education Officers hastily claim that they have to implement EMI because in this ‘adhunik jamana’ [modern age] English is necessary for ‘jagir, bidesh, and gunastariya shikshya” [job, abroad, and quality education]. However, they really don’t have answers to these questions: how EMI helps to achieve all these? Does it mean that students who are not taught in EMI do not get job and quality education?

Schools that practice English as medium of instruction are considered as better schools and are believed to provide quality education. Can EMI help promote quality education?

It’s unfortunate that EMI policy has been considered a panacea for educational issues in public schools. As described above, this policy does not seem to promote quality education in reality. Although it is hard to define what a quality education is, it is evident that the education that helps students develop independent, creative, and critical thinking/leaning skills; appreciate multiple perspectives while engaging in social interactions; and foster an increased awareness of both local and global sociopolitical issues is desirable for all children to succeed in the present world context. A quality education provides students with an opportunity to fully invest their cognitive abilities in making sense of the world where they live in. And a quality education eventually promotes both access and equity in education. What is most disturbing however is that schools are labeled ‘better schools’ or ‘worse schools’ based on whether or not they have implemented an EMI policy. Such evaluative discourses, policies, and practices are a very narrow-view about schools and education and they reduce the meaning of education just to learn English.

Public schools feel a strong pressure to increase the number of students, as mentioned above, to get more teacher quotas. In my interactions with head teachers, teachers, parents, and policymakers, I have found that public schools have introduced EMI to ‘compete with private schools’. Most head teachers argue that the EMI policy is necessary to attract more students in public schools. However, it is evident that the absence of the EMI policy is not the only reason behind the low student enrollment in public schools. Increased migration of people from rural to urban areas, unplanned opening of private schools in both rural villages and urban towns, and decreasing population growth are some of the major reasons behind the issue. Most interestingly, although most public schools have ‘announced’ the EMI policy to attract students, they have not been able to successful to implement the policy. They have asked students to buy English textbooks, but eventually end up translating everything into Nepali. Some head teachers have said that the EMI policy did not even work in their schools so they have started teaching in Nepali. They further said the policy created a lot of confusion among students and teachers. I have seen that students could not answer test items in English unless teachers translated the test items into Nepali. Some teachers give test items before test and dictate their answers in advance.

The assumption that the EMI policy fixes all the issues in public schools is a very myopic view on public education. Public schools (and, of course, private schools as well) can provide a better education in any language and language practices that students understand better and feel comfortable to express themselves.

What is your suggestion regarding the use and practice of EMI in the schools in Nepal?

First, at the theoretical level we must be clear that forcing students to learn academic content knowledge and skills in the language which they have not fully development yet is detrimental to effective learning. Thus imposing English as the medium of instruction, in the guise of an abstract quality education and an imaginary or unrealistic job market, without having an in-depth understanding of language education theories and best practices and without analyzing its educational ramifications may not help students develop strong academic skills and knowledge. Second, there is a clear distinction between teaching English as a language and using it as the medium of instruction. But the current EMI policy and practices are focused more on helping students develop English language proficiency, but not on achieving curricular goals as specified by the Ministry of Education. Most schools and teachers are not teaching Social Studies, for example, but they are teaching the ‘English language’—vocabulary, pronunciation, spelling, sentence structure, and so on. This implies that the entire teaching-learning activities turn to be activities for ‘teaching English’ and schools eventually look like an “English language institute.”

Third, and most importantly, our policymakers must be aware that there are models and best practices in which both language and academic content can be taught using multiple languages simultaneously in the classroom. Recent studies have shown that a monolingual medium of instruction policy does not work well for multilingual students. Thus it is important to redefine the current language education policies and practices including teacher education and professional development programs from a new multilingual perspective.

Finally, as the Ministry of Education has already developed a multilingual education policy and shown its commitment to promote access and equity in education, it is not professionally and institutionally ethical for any organization to focus only on a monolingual approach to education, including teacher training. A multilingual approach to language education not only provides equal space to all languages, including English, but also promotes better language and academic content learning. So it is the right time to redesign our teacher education programs, professional-development modules, and teacher training packages considering our local multilingual complexity and the role of English in it.

Work cited

Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

In my perspective one of the most important factors contributing for ineffective in-service teacher training is the attitude of teachers. Most teachers (not all because few are active and work hard) do not feel such training as an opportunity for their professional development, whereas they feel it as a chance to earn extra money. It is a tragedy that we are yet unable to make them feel the importance of it. Therefore, teachers need to change their attitude and apply the skills learnt in training in their classroom. I think a possible solution for this problem can be a good head teacher. If a head teacher has positive attitude towards training and encourages his teachers to apply new ideas in classroom, teachers cannot afford to be reluctant to transfer the skills in the classrooms.

In my perspective one of the most important factors contributing for ineffective in-service teacher training is the attitude of teachers. Most teachers (not all because few are active and work hard) do not feel such training as an opportunity for their professional development, whereas they feel it as a chance to earn extra money. It is a tragedy that we are yet unable to make them feel the importance of it. Therefore, teachers need to change their attitude and apply the skills learnt in training in their classroom. I think a possible solution for this problem can be a good head teacher. If a head teacher has positive attitude towards training and encourages his teachers to apply new ideas in classroom, teachers cannot afford to be reluctant to transfer the skills in the classrooms. A few classroom visits in Nepal can tell us how ineffective the impact of the government-run in-service training has been. When I ask my graduate students why such a wastage of resources, they say the training does not directly link to the real classrooms, ignores local contexts, and does not address trainees’ mental constructs, their needs and expectations. I fully agree with them. However, for me the main culprits for the ineffective teacher training are the trainers. You may ask why. No trainer has been trained to be a teacher trainer. Each of them has a degree on pedagogy not on andragogy. They do not have a faintest idea of adult learning. Because the trainers in the government system have a permanent position, they do not bother for their own development. And they pass on their attitude to the teachers who they train.

A few classroom visits in Nepal can tell us how ineffective the impact of the government-run in-service training has been. When I ask my graduate students why such a wastage of resources, they say the training does not directly link to the real classrooms, ignores local contexts, and does not address trainees’ mental constructs, their needs and expectations. I fully agree with them. However, for me the main culprits for the ineffective teacher training are the trainers. You may ask why. No trainer has been trained to be a teacher trainer. Each of them has a degree on pedagogy not on andragogy. They do not have a faintest idea of adult learning. Because the trainers in the government system have a permanent position, they do not bother for their own development. And they pass on their attitude to the teachers who they train. The in-service teachers should count themselves fortunate for getting the opportunity to learn and to teach at the same time. Also, they should be gratitude to the concerned authority for providing them with such opportunity. However, it is a sad fact that take away from the training session is less and its translation into the actual classroom teaching is even lesser. There could be multitude of causes behind this ranging from training policy to classroom pedagogy. Since the limited space prevents me from digging depth into the issue, I point out two areas of training drawing on my own experience of teacher and teacher educator both. The first is attitudes. It is not uncommon to hear in the training the participant teachers saying, “It only works here in the training hall, not in our schools”. Most participants have this ‘it doesn’t work’ attitude. First, the training should aim at inculcating positive attitudes in teachers. Only the positive beginning can lead us to the positive ending. Here I am reminded of Thomas Friedman’s famous saying, “If it is not happening, it is because you are not doing it”.

The in-service teachers should count themselves fortunate for getting the opportunity to learn and to teach at the same time. Also, they should be gratitude to the concerned authority for providing them with such opportunity. However, it is a sad fact that take away from the training session is less and its translation into the actual classroom teaching is even lesser. There could be multitude of causes behind this ranging from training policy to classroom pedagogy. Since the limited space prevents me from digging depth into the issue, I point out two areas of training drawing on my own experience of teacher and teacher educator both. The first is attitudes. It is not uncommon to hear in the training the participant teachers saying, “It only works here in the training hall, not in our schools”. Most participants have this ‘it doesn’t work’ attitude. First, the training should aim at inculcating positive attitudes in teachers. Only the positive beginning can lead us to the positive ending. Here I am reminded of Thomas Friedman’s famous saying, “If it is not happening, it is because you are not doing it”.  NCED conducts many in-service teacher trainings out of them TPD is the nationwide training program. These trainings actually implemented by Educational Training Centres (ETC), LRCs and RCs under the guideline developed by NCED. Except TPD, other several training programs like CAS training, MLE training, MGML training, training for the teachers using English as MoI etc.

NCED conducts many in-service teacher trainings out of them TPD is the nationwide training program. These trainings actually implemented by Educational Training Centres (ETC), LRCs and RCs under the guideline developed by NCED. Except TPD, other several training programs like CAS training, MLE training, MGML training, training for the teachers using English as MoI etc. As a resource person, I see there are a couple of reasons why in-service teacher training is not helping to improve the pedagogy in classroom. First of all, the student-teacher ratio in some school is very high. In few schools there are up to 120 students in a single class! Therefore, it is quite challenging to make classroom interactive. When a teacher tries to do something new in group/peers classroom goes out of control and hence they return to old method. Besides, teachers also have to teach more than usual number of periods because of lack of teachers. Therefore, they are not encouraged to try something new because of more work load.

As a resource person, I see there are a couple of reasons why in-service teacher training is not helping to improve the pedagogy in classroom. First of all, the student-teacher ratio in some school is very high. In few schools there are up to 120 students in a single class! Therefore, it is quite challenging to make classroom interactive. When a teacher tries to do something new in group/peers classroom goes out of control and hence they return to old method. Besides, teachers also have to teach more than usual number of periods because of lack of teachers. Therefore, they are not encouraged to try something new because of more work load. First of all, I am quite convinced that in-service teacher-training programs can never be ineffective because they definitely provide some visions and frames for teaching. A trained teacher approaches to the students with some sort of framework, philosophy and guidelines; he or she could deal with students even on the way or on a bus far better than untrained ones.

First of all, I am quite convinced that in-service teacher-training programs can never be ineffective because they definitely provide some visions and frames for teaching. A trained teacher approaches to the students with some sort of framework, philosophy and guidelines; he or she could deal with students even on the way or on a bus far better than untrained ones. The government has envisioned the provision in-service teacher training for the community school teachers for the efficiency and efficacy of teaching methodology exploited while conducting classroom lessons. The considerable amount of national budget allocated in the education sector has been separated for this purpose. Every year such trainings are conducted in RCs, LRCs and educational training centers on need based. It should have resulted in the tremendous improvement in the educational sector of the nation by now but the reality is something beyond our imagination. That is to say, the in-service teacher training does not have tangible impact on the teacher’s educational pedagogy. There can be several factors behind it. Some of the factors that bring about this gap might subsume:

The government has envisioned the provision in-service teacher training for the community school teachers for the efficiency and efficacy of teaching methodology exploited while conducting classroom lessons. The considerable amount of national budget allocated in the education sector has been separated for this purpose. Every year such trainings are conducted in RCs, LRCs and educational training centers on need based. It should have resulted in the tremendous improvement in the educational sector of the nation by now but the reality is something beyond our imagination. That is to say, the in-service teacher training does not have tangible impact on the teacher’s educational pedagogy. There can be several factors behind it. Some of the factors that bring about this gap might subsume: Every year, the government invests a good amount of budget to provide in-service and refresher training to in-service teacher aiming to increase educational quality of the nation. In spite of having such efforts, there is still not much visible improvement in the pedagogy in the classroom. Some prominent causes behind the present situation can be as follows:

Every year, the government invests a good amount of budget to provide in-service and refresher training to in-service teacher aiming to increase educational quality of the nation. In spite of having such efforts, there is still not much visible improvement in the pedagogy in the classroom. Some prominent causes behind the present situation can be as follows: