Setting the Context

I attended a public secondary school in Dhading, which was five kilometres walking distance away from my home. I had to do all the morning chores, prepare meals, eat and run to school as my parents had to go to work on the farm every day. As the classroom was overcrowded with up to seventy students, it was difficult to get a spot in the front row. I had to adjust with six students on a bench at the back of the class, which would make it hard to listen to my teachers. It was challenging to find a cosy place to read, write and listen to the teacher’s lectures. When I recall now, it was tough to get through all this and complete my school education.

Despite the teachers trying to engage us in learning, most of my classmates were inattentive to the teachers’ instructions. The teachers used to crack jokes or share some new things but the students hardly paid attention to their studies. As a result, the teachers were less motivated to teach us and ignored what my classmates were doing in the classroom.

My classmates were from different ethnic communities: Brahmin, Kshetri, Newar, Gurung, Tamang, Gharti, Dalits etc. As they were from diverse groups, they had different beliefs and ways of doing activities. They were basically from working-class families. Yet, some of them belonged to semi-educated families and they were less interested in their study. Nevertheless, I was very excited about my studies.

On a chilly day

It was a cold winter morning. I was teaching ‘The Ant and Grasshopper’ in class ten. I asked my students to write some new words in their exercise book individually. There was some noise, so I tried to control their side talking by cracking a joke. Some of the students who were sitting on the first and second benches were listening to me passionately, whereas the students who were sitting at the back were busy with their personal talk. Again, I told them not to make noise, but their side-talking was ongoing. I further inquired and knew that they were not listening to me clearly. Again, I advised the other side students to have patience and it took around 15 minutes to make them silent.

Moreover, I just had 30 minutes to go. Hence, I revised the previous lesson and made them ready to participate in my large class. Then, I taught my lesson before the lunch bell rang. When I came out of the classroom and I went to the canteen for lunch, I shared my problem with my close friend, who had also been teaching English at a lower secondary level. He listened to me very carefully and agreed with my problem. When I finished the trouble of the classroom. Interestingly, he narrated a story of his classroom that he was also suffering from a similar kind of trouble in large classes. After school, I went back home in the evening and started thinking about my trouble alone.

I realized large class teaching is a complex task and large classes are pretty challenging for the teachers to conduct effective instruction. In such classes, the student number is very high, more than 50, which causes difficult teaching circumstances (Hess, 2006). It is tough for teachers to focus on every student equally. It is considered that students’ engagement and active participation are diminished in large classes, and the frequency and quality of student-faculty interactions are reduced (Cash (2017). Furthermore, Marshall (2004) considers small classes to be very friendly and easy to handle but large classes are highly risky and challenging. Marshall (2004) further highlighted that the analysis of contexts, institutional change in resource allocation and teaching in multidimensional contexts is very thought-provoking.

I conceptualized that teaching in large and under-resourced classes is very tough and tedious throughout my teaching career. In the past, I was a student of a large class where physical infrastructure was not adequate, though we had a blackboard inside the classroom covered with dry grass roof of the building. We didn’t have sufficient classrooms. I still remember when I was a class three grader, and our class was divided into two different classes within a single classroom. It was pretty noisy and hard for the teachers as well. I experienced teaching in an under-resourced context is not an easy job.

Furthermore, I equally reconceptualized that large classes need much personal attention and encouragement to make progress. The students in their learning potential vary considerably due to their language and literacy skills. Thus, we say teaching in large classes is very much like teaching in all other situations; however, handling large classes is more complicated, exhausting, and infinitely more demanding, and challenging.

I explored the reality of large classes through the experience of my research participants who have been teaching a class comprising more than 60 students. I investigated challenges for instance, disruptive students, crises of discipline, and unwanted noise and explored strategies like group work, pair work, and collaborative project works to cope with the large classes with an in-depth study.

I realised that no students get a chance to learn new things in crowded classrooms. They lack the opportunity to grow holistically. Consequently, the prior investment of parents, teachers, schools, and students goes in vain. Based on my experiences as an EFL practitioner in a large classroom, I noted that offering group work and pair work was an effective tool in large-class teaching. The ability to handle large classes provided me an insight through which I germinated useful tips for large class teaching. I reconceptualized the concept of post-method pedagogy by Kumaravedivelu (2006) who persistently claimed that a meaningful pedagogy cannot be constructed without a holistic interpretation of particular situations and that cannot be enhanced without an essential improvement of those particular situations as a theoretical foundation to scaffold his ‘parameter of particularity’. Thus, it is noted that post-method pedagogy prioritises much on creativity, patience, teamwork and leadership.

Major Strategies I Employed in My Large Classroom:

A comprehensible teaching-learning process that ensures efficiency and effectiveness involves the design and implementation of creative and innovative teaching strategies, capable of responding to the individual needs of students and ensuring their academic success, (Jucan,2020). Without level-appropriate activities and contextual strategies, the teaching-learning activities are not making success, (Kumaravadivelu, 2003). Learning style, the learner’s preferred mode of dealing with new information, includes a construct known as cognitive style, (Oxford,1990). In my experience, large-class students have various ways of learning strategies, so I have applied various ways to make them learn. Some of them are as follows.

Engaging students in different project work:

Group work is believed to be allowing students to share ideas, perspectives, and skills among their pair and group. Students learn skills of collaboration and team building in which they develop communication, cooperation and the ability to work effectively with others. It also promotes higher-order thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, as students have to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information collaboratively, (McCormick et al, 2015) So, I designed some activities to attract the student’s attention in his large class every day. I often engage students in different activities. I ask to design a Calander for a group, a Code of Conduct for the classroom for another group and a Wall Magazine for the other groups. Likewise, I instructed them to share their ideas with their friends through their diverse perspectives. Moreover, they started taking feedback from each other. I involved students in some small groups. In doing so, I selected discussion topics that could be of interest to my students. Sometimes I provided them with topics in groups or individually, they searched on the internet and through some reading materials. I knew that all the time group did not work, so to keep every student involved in the group work, sometimes students were provided answers for each of the questions individually first.

Motivating students in pair work:

Working in pairs allows students to give and receive constructive feedback. Pairwork helps in the development of various skills such as teamwork, leadership and interpersonal skills. It is well known that motivation is a force that drives people to work towards a particular outcome (Maslow, 1943). I equally motivated students in pair works where they actively participated and developed a sense of competitiveness in and between other pairs in the classroom. I often motivated them to work on different tasks such as conversation practice, role-playing, problem-solving, debate, collaborative art, etc. Thus, I particularly engaged students in story-writing activities, case study analysis and general problem-solving. Moreover, students would appreciate their tasks in pairs and they learn their commonalities and differences.

Encouraging students to ask questions:

Teaching with questions to my students provided me direct connection with them (Filiz,2009). There is a great role for asking good questions in effective teaching and learning. Hence, I encouraged students to ask questions in my class because this task helps them build critical thinking skills. In this, they asked content-wise questions as it helped them to work together and make sense of the particular subject as mentioned by Kumaravadivelu (2003). Moreover, I motivated my students to raise questions based on their curiosity about the content. Developing questioning abilities indicates students enhance creativity and critical thinking skills. Moreover, questioning habits helped students feel relaxed and learn easily the complex subject matter. It encouraged my students to be active, independent and creative in the large classroom. Besides this, I encouraged my students to speculate on certain incidents, for example, I showed a picture and told them to imagine and connect with the picture. I wrote a sentence, “ If I were in this situation…..”. I let students think, develop their hypotheses, and arrive at a conclusion. This pattern scaffolded students through their positive mindset that they learn interestingly in the large class classroom.

Involving students Think-pair-share procedure:

Think-pair-share (TPS) is a cooperative learning strategy that encourages active participation and engagement among learners. In this think-pair-share technique, students are given a question, and students first think about themselves prior to being instructed to discuss their response with a person sitting near them. Finally, the group shared what they discussed with their colleagues to the whole class and their discourse kept on going (Rowe,1972). Hence, I used the TPS strategy to cope with a large class context. I began my class by asking a specific question about the text. For example; What are the various uses of Artificial Intelligence in education and list them based on your experience. (from one of the chapters of grade 10). Then, my students started thinking about what they knew or had learned about my query. Then, I engaged them to work in pairs with their partner in a small group discussion. Finally, they share what they have collected so far. Thus, the post-method pedagogy entails that students develop coordinating skills, increasing active participation and enhancing their innovative sharing skills.

Major Takeaways:

We teachers struggle in our large classes due to a lack of level-appropriate instructional tools. We often think of managing a large classroom since it needs tactfulness and a lot of experience. Teachers’ ability to explore and develop approaches to observe, analyze and evaluate their teaching for the purpose of accomplishing desired changes. It is an eye-opener and a gateway to make teachers, who are reluctant to bring innovations to their teaching, change their minds and redirect their teaching toward a more contextualized implementation of the strategies suggested to assist them in enhancing their teaching and their students’ learning. Engaging students in various project work, motivating students in group and pair work, encouraging students to ask questions, making level-appropriate fun as well as engagement, and evolving them into TPS strategies are major roadways to creating a learning environment in large classes.

References:

Cash, C. B., Letarago, J, Graether, S. P., & Jacobs, S. R. (2017). An analysis of the perceptions and resources of large classes university. Life Sciences Education, 16(2).

Cash & Marshall, (2007). Between deep and surface: Procedural approaches to learning in

engineering education contexts. Studies in Higher Education,29:5, 605-615, DOI: 10.

1080/0307507042000261571

Gibbs G. (1996). Using assessment to support student learning. The University of East Anglia.

Filiz, S. (2009). Questions and answer method to ask questions and technical information on the effects of teacher education. Social Sciences Journal of Caucasus University.2.

Jucan, D.A., (2020). Efficient didactic strategies used in students’ teaching practice. Social and Behavioural Sciences.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macro strategies for language teaching. Sage.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2005). TESOL methods: Changing tracks, challenging trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59-81.

Hess, N. (2006). Teaching large multilevel classes. Cambridge University Press.

Hess, N. (2007). Teaching large multilevel classes. Cambridge University Press.

McCormick, N. J. and et al, (2015). Engaging Students in Critical Thinking and Problem Solving: A Brief Review of the Literature. Journal of Studies in Education. 5(4).

Oxford, R.L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House/Harper &Row.

Rowe, M. (1972). Wait time and rewards as instructional variables: their influence on language, logic and fate control. ERIC No Edo61103.

About Author: Binod Duwadi has earned an MPhil in English language education from Kathmandu University, School of Education. Mr. Buwadi has been a faculty of English at KUSOM and KUSOED. His research interests include ELT in under-resourced contexts, ELT with ICT integration and Multiliteracy pedagogy.

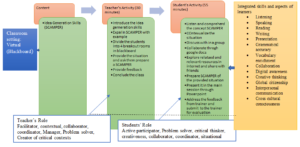

The outbreak of COVID-19 has affected every aspect of human life, including education. The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education system in human history. Social distancing and restrictive movement policies has significantly disturbed traditional educational practices. It has changed education for learners of all ages. Nepal has also suffered a lot due to the lack of adequate and appropriate sustainable infrastructure for the online system. In addition to this, the limited internet facilities in remote and rural areas were the other challenges for virtual academic activities. Many schools remained closed for a long time during the lockdown and some managed alternative ways of teaching. However, the teaching learning activities could not be made effective as expected. The impacts of the pandemic has directly affected the students, teachers and parents.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has affected every aspect of human life, including education. The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education system in human history. Social distancing and restrictive movement policies has significantly disturbed traditional educational practices. It has changed education for learners of all ages. Nepal has also suffered a lot due to the lack of adequate and appropriate sustainable infrastructure for the online system. In addition to this, the limited internet facilities in remote and rural areas were the other challenges for virtual academic activities. Many schools remained closed for a long time during the lockdown and some managed alternative ways of teaching. However, the teaching learning activities could not be made effective as expected. The impacts of the pandemic has directly affected the students, teachers and parents. Prologue

Prologue