The context

The coronavirus (i.e., COVID-19) crisis has brought unprecedented challenges in all the systems including education globally, and communities, particularly in the developing countries, are suffering the most as the public service systems in these countries are not well-planned. The coronavirus pandemic has been a portal that leads the world to reconfigure the future (Roy, 2020) largely different from the one we are/were living. The human sufferings are unprecedented, and of course not measurable either in terms of the economic, social, and psychological losses (both visible and invisible). There are tragic consequences everywhere, and the education sector is one of the most affected ones due to school closure, leaving millions of students from pre-school to the university at homes. The fundamental services of education have halted, with students without textbooks, face-to-face formal interactions, and detachment from their peers. This unexpected context has forced people to think about transformations for the future to enable the pedagogical contexts to recover from the losses, and to cope with the similar future challenging in education systems.

Although schools and universities have tried hard and the best to compensate the loss of schooling by adopting the online mode of instruction, both teachers and students’ limited access to internet facilities, particularly in the least developed countries (LDCs) such as Nepal has become a barrier to holistically shift the physical school to online teaching and learning. This scenario has further accentuated the discourse on equity, concerning the widening gap in terms of access to resources, learning opportunities, human resource management, and the effectiveness of the learning (if any). Similar to Ebola, AIDS, SARS, and Spanish Flu, this pandemic has taught us a lot about humanity, human attachments, health, and urgency of international cooperation. Against this backdrop, in this paper, I have presented my reflection, not necessarily based on strong empirical data, on the potential pathways that we MUST adopt to accelerate transformations in our education systems. By ‘our’, I mean Nepali society, however, my arguments would equally apply to other similar contexts waiting for reforms in their education systems.

The schools are closed for an indefinite time, and standardised tests are suspended. Discourses on educational standards and qualities are extended and enlarged due to the spread of coronavirus. Many people are living with the absence of their friends and families, while others are crammed in their families experiencing probably the longest moment of togetherness with family members. For many, the homes are transferred to online learning stations. The online meetings have covered the walls of Facebook and other social media pages. Perhaps it is the worst ever experience my generation people have had of such pandemic. However, it should also be taken as an opportunity and the right time for countries and relevant communities to unlearn, relearn and rebuild their educational systems to prepare for a better future.

The challenges in schooling

Despite the massive stimulus measures in response to the Covid-19 effects, the global economy is estimated to be hit by recession in 80 years (Guenette, 2020), the deepest since World War II (Al-Samarrai, Gangwar, & Priyal, 2020), and the financial distress will severely impact on the education sector. In other words, this pandemic is likely to impact on several key aspects of education, including financing, resource management, school expansion, and access to learning.

Financing Constraints

The pandemic crisis is likely to leave the education sector vulnerable in terms of infrastructure development including the endeavours to equip schools with technological innovations. In Nepal, the budget allocated for education is inadequate. In the fiscal year 2076/77 (2020/21 AD), the Government allocated 11.64% budget for the education sector (Ghimire, 2020, May 29), which is very less than the budget spent in countries with larger and established economies. Although here is a mere increase in the budget compared to the current fiscal year, two of the ambitious programmes:six-thousand volunteer teacher mobilisation and mid-day meal, will cover more than three quarters (6 billion) of the total increment of 8 billion rupees. It indicates that there will be a limited budget needed to embrace information and communication technology (ICT) in the educational sector.

Human resource development and management

The low-level budget allocations in the education sector, especially in higher education will have serious consequences in managing technical human resources, and technological innovations, due to budget shortages. It is making both short-term and long-term effects on human resources development on handling the technology integration in teaching and learning. Last month, I had a talk with a teacher of a primary school about the use of technology in teaching, and his immediate reaction was “We have a computer and a printer in our school, but we are unable to use them because we could not find a technician to repair them”. His exemplary experience informs us about the level of understanding of what technology in teaching is, and how computer technology is used in schools in remote Nepal. I had a short visit to one of the public campuses in Kathmandu Valley, and during a talk, the campus chief of the campus said, “Sir, we have managed IT on our campus”. I was thrilled and wanted to see how they have made the reform. He took me to one of the carpeted classrooms and showed some computers (seemingly unused for months) and said that it was the IT lab, where students could occasionally go to learn the computer.

These two instances, which I brought here from my own primary experience, tell us how people perceive the use of technology in teaching and learning. In none of the above cases, there was technology integration in pedagogy. They have understood that technology means having computers and using them occasionally for specific purposes such as showing how to open a word file, how to type, and how to print. The development of a broader framework for human resource development in a planned way is a greater challenge ahead.

School expansion and access

Insufficient budget for public education leads to the decline in education outcomes, and poorer education services, which ultimately impacts on parents’ affordability for their children’s education. In Nepal, usually, the households that largely rely on the remittances for education funding of their children and relatives will suffer a lot. It is predicted that expensive private school education will cause an increment in the enrollment in community schools and then pressurise the community schools to accommodate a large number of students. However, community schools at the current state without minimum ICT infrastructure and comfortable learning environment for those students coming from private schools will not be able to hold them and again private schools may take this advantage. Consequently, the social gap between the communities with high and low-income will be much wider than it is.

These challenges, along with many others, need to be addressed in time to meet the new demands of educating in the post-crisis period. I suggest some viable ways to begin the reform in education in Nepal.

Ways ahead

In general, the current context requires us to understand and transform the overall schooling system in a completely different way, as the opportunities for learning have completely gone online. However, the majority of students and teachers, particularly in Nepal, are unable to access online learning for many reasons including the lack of ICT infrastructure, expensive mobile data, and limited or no digital literacy of teachers and students. Complaints have been raised regarding teachers’ efficiency in the use of the online learning management system (LMS) platforms. Teachers’ inability is not due to their negligence but due to their ill-prepared teacher education systems (programmes) that did not equip them with even the basics of integrating technology in pedagogy.

I remember when I was mentoring some students during their field experience in teaching three years ago that they were compelled to follow the lesson planning as par with the lesson plan booklets commercially prepared. This practice barred the students to prepare their lessons autonomously. One of the student teachers asked, “Sir, is it good for English students to follow the same pattern as Science students while preparing lesson plans using this booklet?”. I was speechless, as I knew that this system was not viable, and the student teachers were not even having their own space for altering the patterns of lesson preparation. All the student teachers were filling out the same lesson plan formats provided to them. This is just an example that how we are highly structured in our education systems, following the conventions developed decades ago, and not even asking students to think beyond the box. The main concern I wanted to raise here is that “How does the current strategy of educating and preparing teachers to meet with the growing challenges in learner autonomy, blended learning, and integration of technology in teaching and learning?”.

The crisis has prevailed a need for school transformation by enabling educators and teachers. However, the economic crisis hit by COVID-19 will be a great challenge particularly for developing countries like Nepal to even revive the pre-COVID-19 schools. School transformation is a multifaceted process, including teacher empowerment, readiness, and responsiveness. It is a high time to think about how the teachers can be better equipped to navigate the wounds surfaced in this dark time to reconstruct life anew for themselves and their children through the schooling process. The relevant government agencies can also think of benefitting from the outsourcing of the education services, especially in terms of managing the techno-friendly resources including technical assistance in LMSs design, teacher training, and material development. Although outsourcing of educational services sometimes understood as ‘businessification’ of schooling (Bates, Choi & Kim, 2019), it has been widely adopted as a ‘tested solution’ to many educational problems in many countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong SAR of China.

Enabling teacher agency

There needs a ‘transformation from within’ to meet the challenges generated by this global crisis and a shift from the traditional ‘banking model of education’ (Freire, 1970). Teachers should be prepared for fostering their self-reflexivity and responsibility in shaping their actions in their social contexts. Although teacher agency has been underestimated in the educational contexts of the countries with developing economies, it has been observed that teachers can make the change, provided that they are exposed to an all-enabling environment, both through institutional and professional support. Teachers as reflective practitioners and professional decision-makers (Borg, 2008), also as insiders of the learning process, should be encouraged to come up with their strategies to meet their contextualised learning requirements. The current crisis has also taught us that “the one-size-fits-all” type of blanket strategies, mostly drawn from the global-north contexts, are no longer relevant. In the case of Nepal, owing to its wider demographic diversities such as socio-economic status, language backgrounds, geographical situatedness and cultural orientations, the strategies formed at the federal level will be less likely to succeed requiring greater role of the local government in taking actions to put the policies into practices. In having so, more localised research-supported strategies for maximising teachers’ agentic actions are the must. Teachers are the forefront fighters whenever there is a learning crisis.

Enabling autonomous learning conditions

The transformations can emerge from our actions based on our ideologies and self-regulated efforts to prepare our learners for their life-long learning. The current centralised curriculum development and implementation process have been a problem-posing condition as it does not prepare the learners to be the innovators and self-regulators. The teachers and students are waiting for the state agencies to avail the textbooks for them to start the pedagogies. The curriculum needs to recognise and validate teacher and learner agency in shaping their localised learning environment. The COVID-19 has taught us about making the change from within, not necessarily waiting for some externally sourced interventions facilitating us to transform our professional rituals.

Therefore, it is essential to enable our teachers and students to create their autonomous learning conditions by:

- Developing and providing them with the simplified digital learning programmes

- Accelerating local governments’ engagement on developing learning materials at the micro-level

- Streamlining non-governmental organisations towards facilitating the technical requirements, and

- Supporting parents to educate (or facilitate the learning of) their children.

These strategies are rightly doable to manage and enable autonomous learning conditions at the grassroots level. However, at the same time, none (teachers, students, and parents) should be the victim of the circumstances like the current crisis. Teachers, students, parents, and the local level governmental and non-governmental agencies can be engaged in supporting the children to learn. It can be done by bringing all of them together with complementary roles in scaffolding design by enabling innovative learning environments. For instance, the development partners working in the education sectors can provide the local governments with emergency funding opportunities, and parents of each learner can support learning by engaging them in the family affairs, rituals, and daily chores.

Embracing technology: A blended mode of learning

Despite the well-articulated ICT enhancement policies of the government since the beginning of the 21st century in Nepal, the use of technology in teaching and learning contexts is still in its infancy, particularly in the public education system (Rana & Rana, 2020). However, it is also important that we should be able to grab the highest-level advantage out of the use of technology in teaching and learning, which is very much a core part of learning in this digital era. It should also be noted that technology alone is not a panacea for compensating all kinds of learning gaps, as it is just a tool or a medium to facilitate learning. Therefore, the best feasible way for all learning conditions is to develop a justifiable blend of face-to-face and online (virtual) learning. Although media particularly social media like Facebook and twitter are covered by discourses of the use of ICT that would do everything possible, I believe that it is just a good friend of humans and that human values the kids need now are best transferrable and learned through direct human contact and interaction in a comfortable zone. In our educating system, we should be able to ensure that technology is used to integrate the aspects of our indigeneity of knowledge, cultures, values, and worldviews. Moreover, it is essential to include local epistemologies, heterogeneity, the multiplicity of values, and pluralism to make everyone feel owned.

From the above discussion, I come to a holistic picture of the transformation required as presented in figure 1.

Figure 1 provides a holistic approach to innovations in schooling in such a way that teachers, parents, and the social institutions can actively engage with their agency in the learning conditions that teachers promote autonomy, indigenous pedagogies, and professional development opportunities. A culturally responsive environment that incorporates technology will lead to greater success in meeting our 21st-century learning needs.

Conclusion

This reflection reiterates that evidence-based policymaking for the transformation in Nepal’s education system is essential to prepare our students for a better future, in such a way that our schools remain the “places of mutual respect and a place for understanding human differences and opposing viewpoints” (Arnove, 1994, p. 211) along with their equal access to learning opportunities. We have to be able to institutionalise our indigenous pedagogies that enable our students to equally participate in the learning process. The adoption of technology in teaching and learning might also contribute to foster such inequalities differently, as technology has a double-edged effect. On the one hand, it has created an unequal learning opportunity, and on the other, it has been established as the only alternative mode of learning available during this crisis. All that requires a coherent policy framework that consistently facilitates and controls the local innovations with stronger visions and valuing on teachers. We have a lot to learn from Singapore, where “talk less, learn more” is the core principle of teaching (Hogan, 2014).

Mr Prem Prasad Poudel is currently a PhD scholar at The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. He has worked as a lecturer of English Education at Mahendra Ratna Campus, Tribhuvan University, Nepal for more than a decade. Mr Poudel is a well-established as a teacher educator, teacher trainer and material writer in the field of ELT in Nepal. He has presented papers and published articles in the renowned national and international journals such as Journal of NELTA and Current Issues in Language Planning, respectively. Previously, Mr Poudel also served as the secretary of the Central Executive Committee of NELTA.

References

Al-Samarrai, S., Gangwar, M. & Gala, P. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education financing. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Arnove, R. F. (1994). Education as contested terrain: The case of Nicaragua: 1979–1993. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Bates, A., Choi, T. H., & Kim, Y. (2019). Outsourcing education services in South Korea, England, and Hong Kong: a discursive institutionalist analysis. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2019.1614431

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder.

Ghimire, B. (2020, May 29). The national budget fails to prioritise education, experts say.

https://tkpo.st/2AiSQCZ

Guenette, J. D. (2020). Global economy deepest hit by recession in 80 years despite massive stimulus measures. https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/global-economy-hit-deepest-recession-80-years-despite-massive-stimulus-measures.

Hogan, D. (2014). Why is Singapore’s school system so successful, and is it a model for the west?. The Conversation (12th February). https://theconversation.com/why-is-singapores-school-system-so-successful-and-is-it-a-model-for-the-west-22917

Rana, K., & Rana, K. (2020). ICT Integration in Teaching and Learning Activities in Higher Education: A Case Study of Nepal’s Teacher Education. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 8(1), 36-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.17220/mojet.2020.01.003

Roy, A. (2020). The pandemic is a portal. Financial Times (3rd April). www.ft.com/content/10d8f 5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

Cite as: Poudel, P. (2020, July). Transforming school education: Learning from COVID-19 and pathways ahead. https://eltchoutari.com/2020/07/transforming-school-education-learning-from-covid-19-and-pathways-ahead/

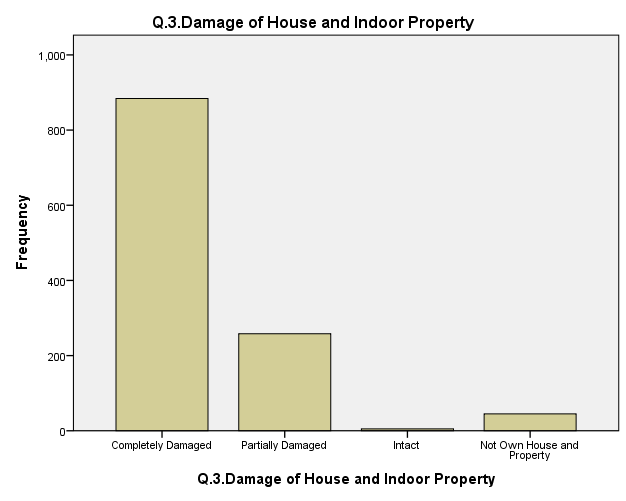

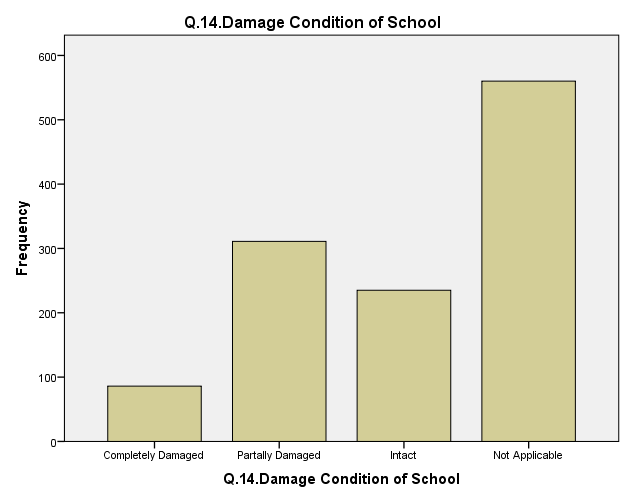

In another article, Dinesh Thapa shares with us his own involvement in the relief and recovery operations in the earthquake-affected areas. He begins with telling his own story and discusses empirical findings about how people are affected by the earthquake. His article is a testimony to redefining the role of “teacher-as-researcher” and an important material for EFL teaching.

In another article, Dinesh Thapa shares with us his own involvement in the relief and recovery operations in the earthquake-affected areas. He begins with telling his own story and discusses empirical findings about how people are affected by the earthquake. His article is a testimony to redefining the role of “teacher-as-researcher” and an important material for EFL teaching.

Though some schools such as St. Xavier’s at Jawalakhel restricted media from the school premises, guardians were allowed to accompany their children to the classrooms.

Though some schools such as St. Xavier’s at Jawalakhel restricted media from the school premises, guardians were allowed to accompany their children to the classrooms.