Prem Phyak

Introduction

Anything that is ‘local’ is generally better in terms of quality and permanence. Let me give some examples: local chicken is tasty, local fruit is hygienic, local vegetable is fresh, and local people make a big difference in your life. What about local literacy? In this short article, I highlight the importance of local literacy in relation to ELT in Nepal. I will also briefly discuss how local literacy in ELT can be promoted in the classroom. Let me start with some perspectives on globalization as the basis of this discussion.

Globalization and Local literacy: What?

We all know that English has become a part of our social and individual lives: it is not only in our education and professions but also in our homes, through television, internet, mobile phones, and other information and communication technologies. Through social networking and new media in particular, English is continuing to work as one of the most powerful means of globalization (See related article in May 2009 issue of NeltaChoutari). We cannot consider the trends of globalization and the spread of English as neutral without being extremely naïve. As Bourdieu (2001) tells us that

“Globalization” serves as a password, a watchword, while in effect it is the legitimatory mask of a policy aiming to universalize particular interests and the particular tradition of the economically and politically dominant powers…It aims to extend to the entire world the economic and cultural model that favours these powers most, while simultaneously presenting it as a norm, a requirement, and a fatality, a universal destiny, in such a manner as to obtain adherence or, at the least, universal resignation. (as cited in Phillipson, 2004)

The term ‘globalization’ has now become a buzz word in every field, and it has very important implications in ELT because the English language is the most influential means of “universalizing particular interests and particular tradition of the economically and politically dominant powers” as Bourdieu argues. To say that we are simply “using” a “common” language for “communicating” across linguistic borders is both absolutely correct but absolutely ludicrous if we don’t “also” recognize/admit that languages belong to societies that wield cultural, social, and political powers through their languages: as language teachers, we must not limit our understanding and scholarship to dictionary definition of “language” because we must also know that the relative difference of the power that different language communities makes huge difference in both material and intellectual terms for people and societies. So, it is important to understand what role English plays in globalization of ideas and practices of dominant cultures. English is considered a ‘global’ language (Graddol, 1997; Crystal, 1997), and the number of researches on the role of English in globalization has increased in the last decade. Recent scholarship in this area helps us understand why and how the role of English as a global language should be assessed critically. The views about the role of globalization in language teaching are, however, more divergent. In their groundbreaking edited book ‘Globalization and Language Teaching,” Block and Cameron (2002) summarize following major views regarding globalization:

- Hegemonically Western, and above all extension of American imperialism

- Extreme of standardization and uniformity

- Synergetic relationship between the global and the local- globalization

We see that the first view takes Gramsci’s ‘hegemony’ and Phillipson’s ‘linguistic imperialism’ about globalization considering it as a means to disseminate the Western and American economic, cultural, political and educational ideologies. In this sense, globalization is another face of Westernization and Americanization. This view is concerned more with the political and ideological discussion which, as I see, does not make more sense in ELT. But the second and third views have a great impact on ELT.

We can relate two major issues – native speakerism and imported method – regarding the ‘standardization’ and ‘uniformity’ in ELT respectively. Standardization here means many things. The most obvious point related to ELT is that in order to maintain standard we have to follow ‘native’ English representing maybe CNN and BBC English. The uniformity can be interpreted as ‘adoption’ of the same textbook, method of teaching and learning material all over the world without considering the ‘local’ socio-cultural context.

The third view – glocalization – is the negotiation between the global and the local in which we find the mixture of the both. At present, this cocktail idea has come to the fore to soothe the criticisms against globalization on the ground of ‘hegemonic’ and ‘imperialistic’ ideology. With this view, we can argue that globalization has its presence at local level as well. We can also say that it is the continuum which has greater impact at the global context but have less impact at the local context. This degree also differs in terms of power, economy and technological advancement. It is obvious that the societies which are poor, powerless and technologically underdeveloped have less impact of the globalization. In this regard, Block (2008) claims

Globalization is framed as the ongoing process of the increasing and intensifying interconnectedness of communications, events, activities and relationships taking place at the local, national or international level. (p.31)

Although it is accepted that ‘local’ components can also be incorporated in the ‘globalization’, questions which have been ignored are: To what extent we have recognized the value of ‘local’ in ELT literacy practice? Which one (the global or the local) is dominant? How can we bring the ‘local’ into ELT pedagogy? In the remainder of this article, I discuss these issues with reference to ELT in Nepal.

Local literacy and local society

Going through various literature and studies regarding literacy (e.g. Wallace, 1999, 2002), we find three major interpretations of local literacy. First interpretation takes local literacy as teaching through local languages. This is concerned more with the anti-linguistic imperialistic discussion pioneered by Phillipson (1992). Second interpretation is grounded on the use of language for daily communication. Teaching of English, in this regard, is considered as a planned and systematic academic endeavor to help ‘local children’ [Nepalese] use English in informal communications outside the classroom. But to what extent, Nepalese children, studying at Grades 1, 2, 3 in rural areas have to speak English while shopping, for example? Does such a projection of the English language as a means to achieve commodity help children achieve true essence of education? These issues are often ignored in academic discussion especially in the global ELT discourse. At the same time, as Cameron (2002) claims, ‘The dissemination of ‘global’ communicative norms and genres, like the dissemination of international languages, involves a one-way flow of expert knowledge from dominant to subaltern cultures” (p. 70).

The third view, which I want to focus in this article, is concerned with the contextual sensitivity of any language literacy including ELT. According to this view, ELT should be in consonance with the socio-cultural and politico-economic realities of particular context where literacy in English takes place. Moreover, this view believes that English language learning is a ‘situated practice’ which happens with the ‘bottom-up’ fashion rather than ‘top-down’ and through so-called expertise-delivered-knowledge. To be more specific, let me ask some questions (although there are many) regarding teaching English in Nepal;

- Do the methods we are adopting while teaching English address our children’s values, beliefs and expectations?

- Are the textbooks that we use for teaching the English language appropriate to our local socio-cultural and politico-economic realities?

We cannot answer these questions in a ‘yes/no’ manner. However, we can be realistic while discussing these issues. Elsewhere, Canagarajah (2002) vehemently argues that the global methods of teaching (e.g. communicative language teaching) have created inequalities in the global pedagogical village. Following a single method with ‘fits-in-all-context’ assumption does not really address learning needs and expectations of local children. Moreover, such an assumption does not empower children rather it marginalizes them psychologically and cognitively as well. This clearly indicates that we need to think about exploring our own practices of teaching English which is relevant to our own soil and people. At the same time, I am not claiming that we should not be aware of the global practices. We should be well informed with them but we should critically scrutinize those practices keeping our realities in view. I think I can discuss much about this when I come to textbook issue in the following paragraph.

In many parts of the world like in Nepal, textbooks are sole source of teaching and learning English. In that sense, textbooks are the most important component of ELT pedagogy in Nepal. However, it is not bizarre to say that, writing and production of textbooks is the most neglected agenda in Nepal. Let me start with the textbooks prescribed by the government. The textbooks in many cases include ‘foreign culture’ as reading texts and situations for conversation, which are difficult to conceptualize for children, are also foreign in some cases. In a way, such situations and texts take children away from their own context. If our goal is to develop reading skills of children, why don’t we bring the texts which deal with local issues, cultures, realities and challenges? Let us research which text (related to local or global text) is effective for enhancing reading skill of Nepalese learners of English.

The textbooks in private schools are more frustrating in terms of local literacy. The global textbooks like Headway/New Headway which are considered to be the global textbooks are prescribed in private schools without any approval from the government. Such global textbooks seem to promote more European and American culture, and project an affluent commodified life style (Gray, 2002). Through the texts like how much Bill Gates earn (New Headway/Upper-Intermediate, 1998) and going on holidays in London, New York, Paris and other expensive cities of the world, the global textbooks are projecting pleasure in life but they are ignoring pain of how a farmer in rural villages works hard to earn and feed his family. Why don’t we have reading texts on holidaying in Jomsom, paragliding from Sarangkot, trekking in Karnali and so on? Can’t we think about including the texts related to Maruni, Kauda, Dhan-nach, Deuda, Goura, Maha-puja, and so on? Are they not useful in teaching English? Of course, YES. On one hand, such texts promote interconnectedness between society and classroom teaching/learning and on the other hand, they help to address precious linguistic and cultural diversity we have. However, we, teachers of English, should always be ready to take the role of ‘transformative intellectuals’ (Kumarivadivelu, 2003) by going beyond our traditional role – teachers as a passive technician in the classroom – to accepting the extended role to show our concern in social reflection and situated practice of teaching English.

Future Directions: Critical Literacy and Postmethod Pedagogy

The above discussion implies that the so-called global textbooks and methods of ELT do not seem to be inclusive and appropriate in diverse world contexts. ELT in Nepal has the same problem. The fundamental reason behind this is that ELT policies we have made are so far shaped by the traditional notion i.e. ELT means teaching about the English language only. But this notion is already obsolete because ‘methods’, ‘textbooks’ and ‘assumptions’ which work better do not fit in other contexts. Moreover, ELT is more than ‘teaching about English’ it is a part of education which is heavily loaded with culture, identity and ideology which need to be scrutinized in relation to local contexts.

How we can promote local literacy is another crucial question we need to discuss. I am not expert at prescribing ideas which work better. But I think, Critical literacy and Postmethod Pedagogy are two major approaches which are helpful to promote ‘local literacy’ practices in Nepal.

The basis of critical literacy is Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) in which he criticises the transmission or ‘banking’ model of education (teachers are depositors and learners are depositories) and advocates for ‘dialogic’ model in which learners are not passive recipient but an active ‘agent’ of whole learning process. We have already discussed this issue in a January 2009 article of NeltaChoutari.

One major issue that critical literacy addresses is inequalities that persist in ELT. It focuses on bringing social issues and controversies into the classroom. Moreover, this approach involves students in a continuous process of thinking critically through a dialogic process in which students are provided opportunities to discuss the issues which have relevance in local socio-cultural context. Thus students clearly see the relevance of learning English in their life which, moreover, promotes local literacy. In this regard, Norton and Toohey (2004) claim

Advocates of critical approaches to second language teaching are interested in relationships between language learning and social change. From this perspective, language is not simply a means of expression or communication; rather, it is a practice that constructs, and is constructed by, the ways language learners understand themselves, their social surroundings, their histories, and their possibilities for the future” (p. 1).

The Postmethod Pedagogy (Kumaravadivelu, 2001) is another approach which may be helpful in promoting local literacy in ELT. The three parameters of the postmethod pedagogy include particularity, practicality and possibility. According to the pedagogy of particularity, “Language pedagogy…must be sensitive to a particular group of teachers teaching a particular group of learners pursuing a particular set of goals within a particular institutional context embedded in a particular sociocultural milieu” (p. 538). Similarly, the pedagogy of practicality “does not pertain merely to the everyday practice of classroom teaching. It pertains to a much larger issue that has a direct impact on the practice of classroom teaching, namely, the relationship between theory and practice” (p. 540). Finally, the pedagogy of possibility is concerned with “participants’ experience which draws ideas not only from the classroom episodes but also from border social, political and economic environment in which they grew up” (p. 542). We can see that ‘local realities’ and ‘experiences’ of participants (teachers, and students) are core of ELT in every world context. This indicates that we need to share our experiences to generate more local knowledge which can be a treasure for the whole ELT community of practice. To this end, we have initiated NeltaChoutari as a voluntary work to tell Nepalese ELT stories to the rest of the world. We hope this sharing through monthly publication in future will provide a basis for producing local materials for ELT in Nepal.

Conclusion

The looming trend of banishing ‘local practices’ due to acceptance of ‘global practices’ as a granted is one of the serious global issues in ELT around the globe. The notion of uniformity and standardization do not seem to be appropriate in linguistically and culturally diverse world contexts. At the same time, the expectations, values and beliefs of learners should be addressed through all kinds of pedagogy including ELT. In this regard, we should think about the use of locally produced materials and be fully informed with the process of adapting ‘creative and critical instructional practices in order to develop pedagogies suitable for their [our] community’ (Canagarajah 1999 p.122). Moreover, as Holliday (2005) has argued, we should discuss whether methodological prescriptions generated in BANA contexts (British, Australia, and North America) have ‘currency’ in our contexts, whether they are locally validated or appropriated. In this sense, whole idea of local literacy in ELT is concerned with the idea of (re)generating locally appropriate methods of teaching, (re)producing local materials using local resources and incorporating local issues and identities and accommodating learners’ experiences through a dialogical process in the classroom.

I am not saying that the ideas discussed in this article address all dimensions of local literacy nor I am saying that we should not be aware of global issues. What I am saying is our full dependence on global methods, norms and textbooks in ELT may not help to promote and sustain our identities and treasure of local knowledge. What I am saying is that we have wonderful ELT practices that we are not able to share with the people from other parts of the world which we need to do urgently. Let me give some example: we have very precious linguistic and cultural diversity in which English is being taught as a foreign language. We have been teaching under the shade of tree and sometimes in the open sky. We have been teaching more than 100 students in the same classroom even without chalk, duster and blackboard. We are teaching students who come from various linguistic, ethnic, religious, cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Don’t you think that such realities and experiences are important source for teaching English? Of course, they are. We need to document these experiences so that other members of ELT community of practice will benefit a lot. Why don’t we take initiation of using local cultural texts (in addition to the texts given in the textbooks), for example, to teach reading and writing skills and see how it works? Can’t we bring stories of child labor, gender discrimination, inequality, poverty and so on to teaching English in the classroom? Of course, YES. But we need to work hard to achieve this end. We cannot make changes overnight but if we collaborative through different means like NeltaChoutari we can accomplish so many things for better ELT in Nepal.

Finally, the future of ELT in Nepal will be even better if we don’t consider teaching of English not simply as teaching about the English language but also as part of education that aims to empower children and to bring some positive transformation in the knowledge-based society. I argue that English teachers are not merely ‘classroom teachers’, we are ‘agent of change’. This is possible only when have a strong foundation at local level. We can access global means only with the strong ‘local foundation’. I would say that the best ELT practice is the practice which accommodates local realities and helps learners to link them with global ones. For this, we need to be aware of maintaining balance between local and global.

(back to editorial/contents)

References

Block, D. & Cameron, D. (2002). Globalization and language teaching. London: Routledge.

Block, D. (2008). Globalization and language education. In S. May and N. H. Hornberger (eds), Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd Edition, Volume 1: Language Policy and Political Issues in Education, 31–43. Springer Science+Business Media LLC.

Bourdieu, P. (2001). Contre-feux 2. Paris: Raisons d’agir.

Cameron, D. (2002). Globalization and the teaching of ‘communication skills’. In Block, D. & Cameron, D. (eds.) Globalization and language teaching. London: Routledge.

Canagarajah, A.S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Canagarajah, A.S. (2002). Globalization, methods and practice in periphery classrooms. In Block, D. & Cameron, D. (eds.) Globalization and language teaching. London: Routledge.

Crystal, D. (1997). English as a global language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Graddol, D. (1997). The future of English? London: The British Council.

Gray, J. (2002). The global coursebook in English language teaching. In Block, D. & Cameron, D. (eds.) Globalization and language teaching. London: Routledge.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward a postmethod pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 35/4, 537-560.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond method: Macrostrategies for language teaching. NewHaven, CO. Yale University Press.

Norton, B. & Toohey, K. (Eds.) (1997).Critical pedagogies and language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Phillipson, R. (2004). Review article: English in globalization: Three approaches. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 3:1, 73 — 84.

Wallace, C. (1999). Critical language awareness: key principles for a course in critical reading. Language Awareness 8, 2:98-110.

Wallace, C. (2002). Local literacies and global literacy. . In Block, D. & Cameron, D. (eds.) Globalization and language teaching. London: Routledge.

Like this:

Like Loading...

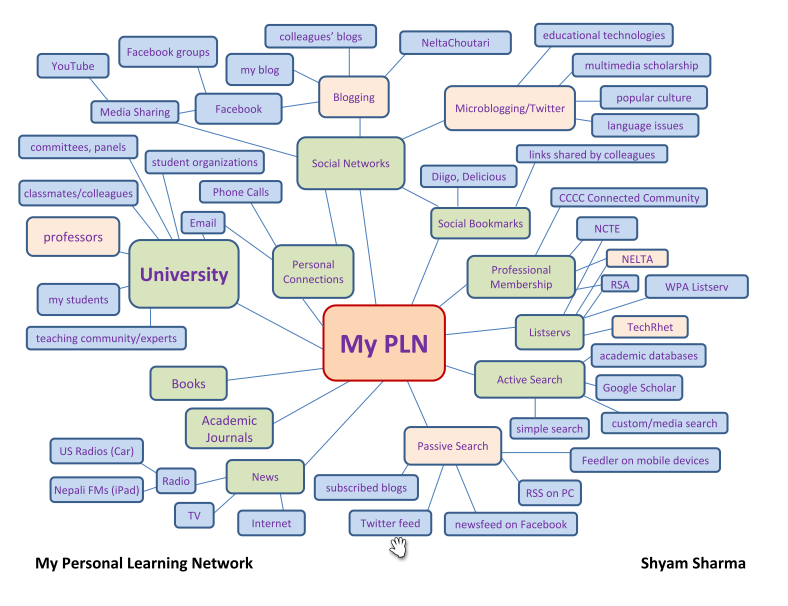

As an example, here is an image in which I attempt to visually describe my own personal/professional learning network (you can click to see a larger image or right-click to download the file). I am still unsure how to integrate many other things that are not in the image and how to better organize an relate what are there, but trying to visually represent my PLN really helped me to think about my professional goals, management of time and energy, and so on. I call mine personal and/or professional because my roles as a learner and a professional overlap quite significantly.

As an example, here is an image in which I attempt to visually describe my own personal/professional learning network (you can click to see a larger image or right-click to download the file). I am still unsure how to integrate many other things that are not in the image and how to better organize an relate what are there, but trying to visually represent my PLN really helped me to think about my professional goals, management of time and energy, and so on. I call mine personal and/or professional because my roles as a learner and a professional overlap quite significantly.